Jex & Britt, Chapter 6: Counterproductive Behavior in Organizations

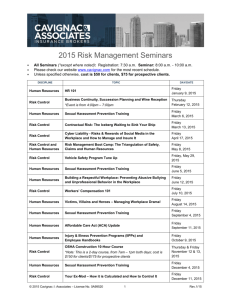

advertisement