Technology strategy of Korean firms and

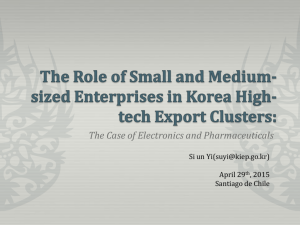

advertisement

Technology strategy of Korean firms and comparative analysis with Japan in display industry and implications for smes Seonmin Junga, Sunyoung Yunb, Joosung J. Leea* Department of Management Science Graduate School of Innovation and Technology Management, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), 335 Gwahak-ro, Yeseong-gu, Daejeon, Republic of Korea a* Corresponding Author: jooslee@kaist.ac.kr a b Abstract The Republic of Korea successfully caught up with Japan in electronics industry during the 1990s and 2000s. The display (LCD) industry is one unique example of the shift in market leadership positions between Japan and Korea. To examine this case, we make a comparative study of Samsung and Sharp. We assume that a major factor involved in the reversed market position is the system integration capability and open innovation practice of Samsung in comparison to Sharp LCD Display. In this paper, we have showed some differences of the process to integrate resources through the internal activities and the external activities of each firm. With a flexible mindset to monitor emerging technological trends, an effort to integrate such resources, and early investment in advanced manufacturing capacity, Samsung was able to leapfrog into the high-tech arenas such as LCD industry. We call this method of learning as “learning-by-integrating”. In addition, this LCD industry case shows that open innovation should be exercised effectively; companies should analyze external environmental factors such as industry economic cycles and policy supporting, evaluate internal competency, and then create an open innovation culture in order to compete and reap from technological breakthroughs in today’s economy. This paper shows some distinctive technological strategies for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as it offers insight on how Korean companies have excelled so well in such a short amount of time. It also discusses what SMEs must do in order to cope with the new technology-convergence paradigm to stay ahead. Introduction I n 1990, Japan had many leading global companies in the electronics industry. However, in 2000, the Republic of Korea’s companies became the leading players in the electronics industry. Today, as Japan faces an economic crisis, and practitioners and scholars suggest that changing the innovation model did not just help to develop technology but also took the business model into consideration (Senoh, 2011). According to Inchijo (2006), the traditional Japanese business system is good at cumulative technological innovation, which produced the competitiveness of such industries as automobiles and digital cameras. However, the Japanese business model, which is a “go-it-alone” attitude, 32 TECH MONITOR • Apr-Jun 2014 is being challenged. Particularly in the field of electronics, Japan integrated its manufactures and began offering a wide range of products while maintaining its reliance on proprietary in-house technology, which may have caused it to lose its competitive position to a more specialized component company that exploits open systems and modularity. System integration has been regarded as an important capability in the operations, R&D strategy, and competitive advantage of major corporations in a wide variety sectors such as computing, telecommunications, military systems, and aerospace (Hobday et al., 2005). Lansiti and West (1997) showed that superior technology integration is the factor to achieving superior R&D productivity, speed, and good products and by utilizing this approach, US semiconductor companies had regained their market position in 1990. Hobday et al. (2005) referred to the fact that there are‘two faces’about system integration. The first face is the internal activities of firms by developing and integrating the input to produce new products.The second face is the external activities of firms by integrating components, skills, and knowledge from outside of firms to produce more complex products and services. In recent years, the second face has become more important. Chesbrough and Crowther (2006) surveyed twelve firms on open innovation adoption and identified as early adopters of open innovation in mature and assetintensive industries, such as aerospace and chemicals in the United States. Other scholars such as Vanhaverbeke (2006), and Van der Meer (2007) investigated the adoption of open innovation in Dutch innovative firms operating in several heterogeneous sectors, such as food and beverage, chemicals, and machinery and equipment. As the previous research shows the differences in the countries helps to create an open or closed environment irrespective of the type of industry and then motivates companies to accept open innovation. Complicated factors have led to the change in market position. However, based on the previous supporting papers, the authors assume the factors involved in the changing market position are integration ability and open innovation in Japan and Republic of Korea’s electronic companies. The LCD industry is one example of the change in market positions between Japan and Republic of Korea (Fig 1). The study involved Sharp in Japan and Samsung LCD in Republic of Korea, which were studied from the late 1990s to the early 2000s. Sharp and Samsung are Technology strategy of Korean firms and comparative analysis with Japan compared by their perspectives regarding open innovation. Traditionally, the former leading industrial enterprises feared remarkably strong competition from many newer companies, so they developed a closed innovation strategy. Even though Samsung follows Sharp in the LCD market, Samsung was the number one leading global company in 2010, followed by Sharp. Samsung consisted of task force teams that focused on developing LCDs and utilizing outside networking. Samsung used its investment capability and strategic leadership to maximize its technology through open innovation. For those reasons, this paper analyzes Samsung and Sharp. After this, the authors show distinctive strategies for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as it offers insight on how Korean companies have excelled so well in such a short amount of time and discuss what SMEs must do in order to cope with the new technologyconvergence paradigm to stay ahead. Theoretical background Prencipe et al. (2003) presented drivers of system integration, which include the increasing complexity of products and systems such as the rapid pace of technological change and the increasing breadth of knowledge, modular design strategies, and change in the competitive environment. The LCD industry, which has typical characteristics such as capital-intensity, technology-intensity, rapid replacement speed of product production technologies, large fluctuations in product prices, and spread of international horizontal outsourcing (Hsiao et al., 2011), is a good case to utilize integration capability. In order to utilize integration capability, firms have to establish relationships with a variety of partners. As noted by Dittrich and Duyster (2007), inter-organizational relationships might be established with an explorative or exploitative intent, the former enabling the inflow of external knowledge and the latter allowing for the external exploitation of technological opportunities. Best (2003) considered the question of the technological resurgence of US information and communication technology (ICT). In this study, the author pointed out a new competitive advantage in the innovative Figure 1: Change of market positions in LCD industry Source: Jang,S.W., & Yang. B. 1999. The successful of TFT LCD. Published by Samsung Economic Institute. CEO information 209 and Displaysearch. 2010. dynamics of regional clusters. As Kostoff (1994) presented that “the entrepreneur can be viewed as an individual or group with the ability to assimilate this diverse information and exploit it for further development. However, once this poll of knowledge exists, there are many persons or groups with capability to exploit the information, and thus the real critical path to innovation is more likely to be the knowledge poll than any particular entrepreneur”. Through these clusters, firms could develop and use the ‘poll of knowledge’ from other partners, and eventually could enhance their technologies, skills, and products. The integration capability means firm’s capability to integrate their internal resources such as technology, skills, knowledge from external resources. In this regard, open innovation is similar to system integration in utilizing ideas and knowledge from outside of firms. Implementing open innovation requires the innovating firm to act upon on a number of managerial levers along which the change process unravels. The knowledge management process represents an area where open innovation has an impact. Open innovation is, in fact, all about leveraging and exploiting knowledge generated inside and outside, thereby enabling firms to develop and exploit innovation opportunities. Implementing open innovation requires using the knowledge management process to share and transfer knowledge within the firm and to the external environment. Managers might be required to intervene on the knowledge management process in favor of the introduction of the new innovation management paradigm. Polanyi and Van den Berg (1996) delineate knowledge as two dimensions: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is knowledge that is codified and transmittable in formal, systematic language. It, therefore, can be acquired in the form of books, technical specifications, and designs or embodied in machines. Tacit knowledge, in contrast, is so deeply rooted in the human mind and body that it is difficult to codify and communicate and can be expressed only through action, commitment, and involvement in a specific context. Kim (1998) referred the fact that tacit knowledge can be acquired only through experience, such as observation, imitation, and practice. Therefore, closed innovation companies just transfer tacit knowledge through in-house members without using the knowledge management process. On the other hand, when pursuing an open innovation company, the knowledge management process needs to operate in and out of boundaries. Therefore, the knowledge management process is the managerial lever of open innovation. Open innovation implies an extensive use of organizational relationships to in-source external ideas from a variety of innovation sources and to market internal ideas that fall outside the firm’s current business model using a range of external market channels. This requires the innovating firm to establish relationships with a variety of partners, in particular universities and research institutions, suppliers, and users. As noted by Dittrich and Duyster (2007) in their analysis of the innovation network of Nokia, inter-organizational relationships might be established with an explorative or TECH MONITOR • Apr-Jun 2014 33 Technology strategy of Korean firms and comparative analysis with Japan exploitative intent, the former enabling the inflow of external knowledge (outside-in dimension of open innovation), and the latter allowing for the external exploitation of technological opportunities (inside-out open innovation). Laursen and Salter (2006) go further by identifying, as a key factor in the shift towards open innovation, a change in the way by which firms search for new ideas and technologies. Davide, Vittoroio and Federico (2011) suggest that open innovation increase both firms’ search breath, which is the number of external sources they rely upon in their innovative activities, and firms’ search depth, which is the extent to which firms draw deeply from the different external sources of their innovation networks. The firm’s adaptive culture has an effect on utilizing external resources. Many firms shift their innovation model from a closed approach to an open system approach. However, there are some differences about culture requirements between two approaches. First, evidence can be found in the literature arguing that employees of an open innovation organization need to be much more adaptive than their counterparts when applying a closed innovation approach (Chesbrough, 2003). Openness to new ideas is addressed by taking into account employees’attitudes toward external technology sourcing (Phillipp and Jens, 2010). The underlying attitude that will be discussed is the not-invented here (NIH) syndrome that generally denotes a negative attitude toward external technol- ogy sourcing. Accordingly, it is critical for the success of open innovation to overcome certain attitudes that inhibit the firm from fully exploiting its potential (Lichtenthaler et al., 2010). Many scholars and practitioners have referred to the NIH syndrome to describe the negative effects resulting from an overemphasis on internal technologies, ideas, or knowledge (Chesbrough, 2006). Comparative case study The business cycle has the recurrent phenomenon in which market demand tends to peak in one year only to plummet one or two years later. The business cycle can be observed in a variety of sectors and it manifests itself in an especially vicious form in innovation-driven and/or capitalintensive environments. Figure 2 shows the LCD industry cycles. Samsung poured investment funds into an industry as the very time when prices were falling, production was falling, and other firms were cutting back on investments with no end in sight. It was an act of faith believing that the downturn would be followed by an upturn. Finally, Samsung created 3.5 generation and changed the market rules (Jang and Yang, 1999). In contrast, in 1995-1996, when the industry tipped it into a second downturn due to excess capacity and the world financial crisis happened in 1997, Sharp delayed investing in and producing the huge TFT panel and remained with its own strategy of focusing on small LCD panel production. Figure 2: Crystal cycles and strategic initiatives Source: Kerry, L. C. 2004. Asian TFT-LCD market drives manufacturing trends. Published by ElectroIQ. 34 TECH MONITOR • Apr-Jun 2014 Moreover, Figure 3 shows the trajectory of R&D intensity from 2000 to 2012. As Figure 3 demonstrates, for a certain period of time, Samsung and Sharp have shown an opposite tendency in R&D investment. According to Berchicci (2012), firms with a high level of R&D capacity are more efficient in recognizing and assimilating crucial knowledge from external sources, while firms with a limited basic R&D capacity are hard to screen, recognize, exploit and finally benefit from new external knowledge. In other words, in order to efficiently utilize external knowledge, firms also have to possess their own capabilities. Samsung has steadily increased their R&D intensity; however, Sharp has lost its own R&D capability during the same period. In order to catch up with advanced technology, in 1996, Samsung opened a R&D lab in Japan to take advantage of unemployed Japanese engineers to acquire technology from without licensing it. Even though it entered the new LCD panel industry, it had supplier networks with Japan’s microfabrication process equipment companies. At first, it acquired each process of TFT-LCD module manufacturing technology and gradually collaborated with advanced technology companies. In contrast, Sharp kept its knowledge and technology under wraps in order to remain competitive. They usually conducted new technology developments in secrecy and did not reveal outside of the patent application. They also transferred tactical knowledge within the organization. When Sharp established the Kameyama plant, the LCD panel department and LCD TV department’s engineers worked together to determine whether that type of tacit knowledge could be smoothly adjusted. In Kamyama, the LCD technology development department engineers were directed to oversee the development process of LCD TVs; to manage performance, engineers developed a new LCD, which was assembled in front of TV division engineers. The combined development of new LCD technology and TV production was becoming more complex for Sharp and created a significant barrier to protecting its intellectual property. The Republic of Korea and Japan form the LCD clusters. Samsung was located in Tangjeong “Crystal Valley”, which is the Technology strategy of Korean firms and comparative analysis with Japan 12.00 10.00 R&D Intensity % world’s largest LCD cluster. The cluster contributes to a competitive and cooperative open environment. Samsung has partnerships with other companies, universities, and research institutes. Samsung was focusing its partnerships on technology and market research, and not just on outsourcing. The inter-industry results in companies adopting external knowledge and technologies into internal activities. Sharp is the central company in Japan’s largest LCD industry in Kameyama, where it consistently has a vertical integration, from materials and parts to the final products. In contrast to Samsung, Sharp outsourced the manufacturing of machines and parts but not the partnership. They just ordered customized equipment and regularly changed subcontractors. Samsung sought partnerships to improve its development of LCDs within the clusters; on the other hand, Sharp attempted to reduce the cost of non-core businesses and functions unrelated to technology or products by outsourcing within the clusters. Samsung had shown an active strategy to form relationship with competitors. For example, Samsung and Sony have competed in most of the domains; however, in 2003, Samsung and Sony established a joint LCD venture (S-LCD). The two companies joined through the patented technology, which enabled them to increase sales, because the companies produced the product continually and faster thanks to the accumulation of patents, which saved money on new patent development costs. They shared information with each other, excluding confidential design information. Sony accepted the stable TV panel without testing, and Samsung improved its imaging technology for LCDs. In case of Sharp, they created a closed innovation environment, networking through a horizontal division inside the company. Until the Kameyama plant began to produce LCD panels, the development of LCD technology and the TV Sector Development Division were separate from each other. Sharp was locked in the company’s pride and would not accept outside innovation, which resulted in a decrease in competitiveness, brand on Sharp’s decreasing TV sales. It had missed the opportunity to look for the market demand because of cultural lock-in. 8.00 6.00 Sharp Samsung 4.00 2.00 0.00 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Year Figure 3: R&D intensity (R&D expenditure/net sales) Discussion and conclusion This study seeks to provide a comprehensive overview from theoretical and practical perspectives of integration capability and open innovation in the LCD industry. Samsung utilized the advance knowledge from outside the company and was able to leapfrog into the high-tech arenas such as LCD industry with a flexible mindset to monitor emerging technological trends, an effort to integrate such resources, and early investment in advanced manufacturing capacity. However, without understanding the resources from outside of firm, it could not have been possible for Samsung to lead the LCD industry. We call this method of learning as “learning-byintegrating”. However, Sharp protected its knowledge and wanted to reduce the cost of non-core business activities or functions outside of technology or product development by outsourcing within clusters. Through these results, we could show some distinctive technological strategies for SMEs as it offers insight on how Korean companies have excelled so well in such a short amount of time. Several CEOs for Korean SMEs also emphasize on the capability for finding opportunities by monitoring technology trend and cumulating their own technology with resources from firms’outside.‘Dasan networks’, which is the first network device production company of Republic of Korea, found their new business items, which are the internet transaction and network device, when they had been working at Silicon Valley. After then, through joint venture with Siemens, they learn their know-how and cumulate their own technology capability. In case of Humax which is the global set-top box maker for digital TV in Republic of Korea, the CEO said that there are opportunities for ventures or SMEs if the environment began to change. When they established venture business in 1989, they monitored the changes of technology trend from analog to digital and decided to entrance digital products business. In 21 years after beginning venture business, their sales reached KRW 1 trillion. In recent years, they finished five M&As for trying to implement open innovation in order to find new business beyond the set-top box from outside of firm. In conclusion, in order to cope with the new technology-convergence paradigm to stay ahead, SMEs should analyze external environmental factors such as industry economic cycles, evaluate internal competency, and then create an open innovation culture in order to compete and reap from technological breakthroughs in today’s economy. References ü Berchicci, L. (2012), “Towards an Open R&D System: Internal R&D Investment, External Knowledge Acquisition and Innovative Performance.” Research Policy, dopen innovation:10.1016/j.respol.2012.04.017. ü Best, M. H. (2003), “The Geography of Systems Integration,” in A. Prencipe, A/ TECH MONITOR • Apr-Jun 2014 35 Technology strategy of Korean firms and comparative analysis with Japan Davies and M/ Hobday (eds), The Business of Systems Integration. Oxford University Press: Oxford. ü Chesbrough, H. (2003), “Open Innovation, The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology,” Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. ü Chesbrough, H., and A. Crowther, (2006), “Beyond High-Tech: Early Adopters of Open Innovation in Other Industries, R&D Management, Vol. 36(3), pp. 229–236. ü Davide, C., Vittorio, C., & Federico F. (2011), "The open innovation journey: How firms dynamically implement the emerging innovation management paradigm", Technovation, Vol. 31(3), pp. 34–43. ü Dittrich, K., and G. Duyster (2007), “Networking as a Means to Strategy Changes: The Case of Open Innovation in Mobile Telephony,” Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 24, pp. 510–521. ü Hobday, M., A. Davis, and A. Prencipe (2005), “Systems Integration: A Core Capability of the Modern Corporation,”Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 14, pp. 1109–43. ü Hsiao C. T., P. I. Chang, C. W. Chen, H. H. Huang (2011), “A System View for the High-Tech Industry Development: A Case Study of Large-Area TFT-LCD Industry in Taiwan,” Asian Journal of Technology innovation, Vol. 19(1), 117–132. ü Inchijo, K. (2006), “Strategic Management of Knowledge-Based Competence: Sharp Corporation.” In H. Takeuchi, and T. Shibata (eds.), Japan, Moving Toward a More Advanced Knowledge Economy Vol. 2: Advanced Knowledge-Creation Companies: 41–50. Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. ü Jang, S. W., & Yang. B. (1999), The successful of TFT LCD. Published by Samsung Economic Institute, CEO information 209: 1–20. ü Kim, L. S. (1998), “Crisis Construction an Organizational Learning,” Organizational Science, Vol. 9(4), pp. 506–518. ü Kostoff, R. N. (1994), “Successful Innovation: Lessons from the Literature,” McKinsey Quarterly, Vol. 2, pp. 99-105. ü Lansiti, M., and J. West (1997), “Technology Integration: Turning Great Research into Great Products,” Harvard Business Review, May–June. ü Laursen, K. and A. Salter (2006), “Open for Innovation: the role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 27, pp. 131-50. ü Lichtenthaler, U., H. Ernst, and M. Hoegl (2010), “Not-sold-here: How Attitudes Influence External Knowledge Exploitation,” Organization Science, Vol. 21(5), pp. 1054–1071. ü Phillipp, H., and L. Jens (2010), “Open and Closed Innovation: Different Innovation Cultures for Different Strategies,” Technology Management, Vol. 52(3/4), pp. 322–342. ü Polanyi, L., and M. H. van den Berg (1996), “Discourse Structure and Discourse Interpretation,” In P. Dekker & M. Stokhof (eds.), Proceedings of the Tenth Amsterdam Colloquium: 113-131, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam. ü Prencipe, A., A. Davies and M. Hobday (eds) (2003), The Business of Systems Integration, Oxford University Press, Oxford. ü Senoh, G. (2011), “The Reason Failure of Japanese Company Business Even Having the Technology,” Seoul: 21 Century Books Press [translated from Korean by Shin, E. J.]. ü Van der Meer, H. (2007), “Open innovation – The Dutch threat: Challenges in Thinking in Business Models,” Creativity and Innovation Management, Vol. 16/2(June), pp. 192–202. ü Vanhaverbeke, W. (2006), “The InterOrganizational Context of Open Innovation,” In H. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, and J. West (eds.), Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm: 205–219. Oxford: Oxford University Press. n Global Innovation Index 2014 The Global Innovation Index 2014 was released jointly by World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), Cornell University, INSEAD and its Global Innovation Index 2014 edition Knowledge Partners, the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), du and Huawei. Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Sweden topped this year’s Global Innovation Index, while Sub-Saharan Africa posted significant regional improvement in the annual rankings. The GII leaders have created well-linked innovation ecosystems, where investments in human capital combined with strong innovation infrastructures contribute to high levels of creativity. In particular, the top 25 countries in the GII consistently score high in most indicators and have strengths in areas such as innovation infrastructure, including information and communication technologies; business sophistication such as knowledge workers, innovation linkages, and knowledge absorption; and innovation outputs such as creative goods and services and online creativity. The GII 2014 surveys 143 economies around the world, using 81 indicators – to gauge both their innovation capabilities and measurable results. Published annually since 2007, the GII is now a leading benchmarking tool for business executives, policy makers and others seeking insight into the state of innovation around the world. This year’s study benefits from the experience of its Knowledge Partners: the Confederation of Indian Industry, du and Huawei, as well as of an Advisory Board of 14 international experts. For more information, contact: Media Relations Section, World Intellectual Property Organization Tel: (+41 22) - 338 81 61 / 338 72 24; Fax: (+41 22) - 338 81 40 Web: http://www.wipo.int 36 TECH MONITOR • Apr-Jun 2014