1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN

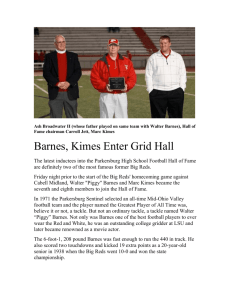

advertisement