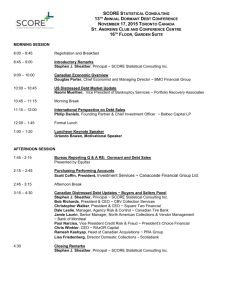

Basic Urban Infrastructure and Its Community

advertisement