CE 311 - Evidence-Based Decision Making

Evidence-Based Decision Making: Introduction and Formulating Good Clinical Questions

Jane L. Forrest, EdD, BSDH

Continuing Education Units: 2 hours

Online Course: www.dentalcare.com/en-US/dental-education/continuing-education/ce311/ce311.aspx

Disclaimer: Participants must always be aware of the hazards of using limited knowledge in integrating new techniques or procedures into their practice. Only sound evidence-based dentistry should be used in patient therapy.

The primary learning objectives for this course are to: 1) increase your knowledge of evidence-based concepts, principles and skills, and 2) specifically how to formulate a good clinical question in order to find relevant evidence to answer that question.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement

• Jane Forrest has done consulting work for P&G.

ADA CERP

The Procter & Gamble Company is an ADA CERP Recognized Provider.

ADA CERP is a service of the American Dental Association to assist dental professionals in identifying quality providers of continuing dental education. ADA CERP does not approve or endorse individual courses or instructors, nor does it imply acceptance of credit hours by boards of dentistry.

Concerns or complaints about a CE provider may be directed to the provider or to ADA CERP at: http://www.ada.org/cerp

Approved PACE Program Provider

The Procter & Gamble Company is designated as an Approved PACE Program Provider by the Academy of General Dentistry. The formal continuing education programs of this program provider are accepted by AGD for Fellowship, Mastership, and Membership

Maintenance Credit. Approval does not imply acceptance by a state or provincial board of dentistry or AGD endorsement. The current term of approval extends from 8/1/2013 to

7/31/2017. Provider ID# 211886

1

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

Overview

The Evidence-based Decision Making (EBDM) process provides a mechanism for staying current in practice by addressing gaps in knowledge so that the clinician can provide the best care possible. To accomplish this EBDM requires understanding new concepts and skills, the first and often the most difficult is how to ask an answerable question. This question provides the basis for identifying the key terms for conducting an efficient search, the second step of the EBDM process. These two steps provide the basis for the three that follow: critically appraising the evidence, applying the results in clinical practice, and evaluating the outcome. The EBDM approach recognizes that clinicians can never be completely current with all conditions, medications, materials, or available products, and provides a structure approach to keeping current.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this course, the dental professional should be able to:

• Define Evidence-Based Medicine/Practice.

• Define Evidence-based Decision Making and its purpose.

• Explain why evidence-based practice is not just a new term for an old concept.

• Identify two principles of EBDM.

• Discuss the need for EBDM.

• Identify the levels of evidence and premise upon which they are based.

• Describe the 5 steps and skills necessary for EBDM.

• Formulate a good question using the PICO process.

• Discuss the benefits of EBDM.

Course Contents

• Introduction - What is Evidence-Based

Decision Making?

• Is Evidence-based Practice a New Term for an

Old Concept?

• Principles of EBDM

• The Need for EBDM

• Levels of Evidence

• Evidence-Based Decision Making Skills and the 5-Step Process

• Evidence-Based Decision-Making in Action

• Applying the PICO Process

• Structuring the PICO Question

• Benefits of EBDM

• Conclusion

• Course Test

• References

• About the Author

Introduction - What is Evidence-Based

Decision Making?

Evidence has always contributed to clinical decision-making; however, with the proliferation of clinical studies and journal publications, keeping current with relevant research is nearly impossible. Because we rely on well-designed research studies to demonstrate the efficacy and effectiveness of diagnostic tests, treatment strategies, new materials, and products, knowing how to find the scientific evidence is an essential component for clinical practice.

Using evidence from the medical literature to answer questions, direct clinical action and guide practice was pioneered at McMaster University,

Ontario, Canada in the 1980’s. As clinical research and the publication of findings increased, so did the need to use the medical literature to guide practice. The old clinical problem-solving model based on individual experience or the use of information gained by consulting authorities

(colleagues or text books) gave way to a new methodology for practice and restructured the way in which more effective clinical problem-solving should be conducted. This new methodology was termed Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) definition is currently stated as:

1 and its

The integration of the best research evidence with our clinical expertise and our patient’s unique values and circumstances.

2

Rather than refer to medicine, often this definition has been broadened to mean ‘practice’ or

2

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

‘healthcare’ and is the definition we are using for

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) .

Several professions have adapted this definition to make it specific to their discipline. For example, the American Dental Association (ADA) defines “evidence-based dentistry” (EBD) as: an approach to oral health care that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentists’ clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences.

3

Inherent in these definitions is the recognition that research evidence is a valued component of the clinical decision-making process, and the intent is that the use of current best evidence does not replace clinical skills, judgment, or experience but provides another dimension to the decisionmaking process that also considers the patient’s preferences (Figure 1).

4-6 It is this decision-making process that we refer to as Evidence-Based

Decision Making (EBDM) and is defined as:

Figure 1. EBDM Process

©2001 Forrest, NCDHR

The formalized process of using the skills for identifying, searching for and interpreting the results of the best scientific evidence, which is considered in conjunction with the clinician’s experience and judgment, the patient’s preferences and values, and the clinical/ patient circumstances when making patient care decisions.

Again, EBDM is not unique to medicine or any specific health discipline, but represents a concise way of referring to the application of evidence to clinical decision-making.

Is Evidence-based Practice a New Term for an Old Concept?

The use of evidence in practice is not new. What is new is the nature of the clinical evidence itself in terms of the methods for gathering it [randomized controlled trials and other well-designed methods], the statistical tools for synthesizing and analyzing it [systematic reviews and meta-analysis], and the ways for ways for accessing [electronic databases] and applying it [evidence-based decision-making and practice guidelines].

7,8,9

In other words, evidence-based practice is not just a new term for an old concept and as a result of advances, practitioners need:

1. more efficient and effective online searching skills to find relevant evidence, and

2. critical appraisal skills to rapidly evaluate and sort out what is valid and useful, and what is not.

10

EBDM is the formalized process and structure for learning these skills with the purpose of closing the gap between what is known and what is practiced in order to improve patient care based on informed decision-making.

Principles of EBDM

Evidence-based decision-making is about solving clinical problems and involves two fundamental principles :

1. Evidence alone is never sufficient to make a clinical decision . Initially, the focus of EBM emphasized using randomized clinical trials and other quantifiable methods. However, as EBM has evolved, so has the realization that the evidence from clinical research is only one key component of the decision making process and

11 does not tell a practitioner what to do.

2. A hierarchy of evidence exists to guide clinical decision-making .

9 EBDM is a structured process which incorporates a formal set of rules for interpreting the results of clinical research and places a lower value on authority or custom.

In contrast to EBDM, traditional decisionmaking, relies more on intuition, unsystematic

3

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

clinical experience and pathophysiologic rationale.

9,12

The Need for EBDM

An evidence-based approach has emerged in response to the need to improve the quality of health care and to demonstrate the best use of limited resources.

4,13 Forces driving the need to improve the quality of care include:

1. variations in practice,

2. slow translation and assimilation of the scientific evidence into practice, 4,14-16

3. managing the information overload, and

4. changing educational competencies that require students to have the skills for lifelong learning.

6

1. Variations in Practice Patterns

Substantial advances have been made in our knowledge of effective disease prevention measures and of new therapies, diagnostic tests, materials, techniques and delivery systems, and yet the translation of this knowledge into practice has not been fully applied. Variations in practices among dental clinicians are well documented, whether it involves diagnostic procedures, treatment planning 17,18 and treatment, 19 or prescribing antibiotics, such as was found among endodontists 20 and general practitioners.

21

2. Slow Translation and Assimilation of

Research Findings into Practice

Far too often variations in practice occur due to a gap between the time current research knowledge becomes available and its application to care. Consequently, there is a delay in adopting useful procedures and in discontinuing ineffective or harmful ones.

22-25

One example has been the use, or lack of use, of dental sealants.

24 Although their effectiveness have been well documented over the past 3 decades, only 18.5% of US children and youth ages 5-17 have one or more sealed permanent teeth (1988-1991 data) 26 and goals for Healthy

People 2020 have been retained, but modified to increase the proportion since the 2010 goals were only set at 50%.

27

Assimilating scientific evidence into practice requires that clinicians keep up to date by reading extensively, attending courses and taking advantage of the Internet and electronic databases to search for published scientific articles. However, colleagues and personal journal collections tend to be the primary information sources for treatment decisions, rather than the scientific literature.

28-30 Treatment decisions tend to reflect the knowledge, skills and attitudes learned as a student, 8,25,31 and trends indicating that the longer clinicians are out of school, the bigger the gap in their knowledge of up-to-date care, 31,32 as demonstrated by the knowledge, opinions and practices of dentists and dental hygienists in providing oral cancer examinations.

33,34 This reinforces the need to learn evidence-based information seeking behaviors and critical analysis skills while still in school.

3. Managing the Information Overload

In addition to influencing variations in practice and the slow translation and assimilation of scientific evidence into practice, it is physically impossible to keep up to date with the increasing number published articles. With the number of good clinical trials and meta-analyses increasing at a rate of 10% per year 35 and located in over

700 dental journals world-wide, knowing which journals to subscribe to that have the relevant articles related to an individual’s practice is nearly impossible. To stay current in general dentistry, one would have to identify, obtain, read and appraise 6 articles per week, 52 weeks per year.

35

The challenge is to find relevant clinical evidence when it’s needed in order to help make well-informed decisions. Evidence-based practice is now possible due to increased access to relevant clinical findings via development of online databases and computers that enable quick access to the scientific literature. Being able to search electronically across hundreds of journals for specific answers to patient questions or problems solves this problem.

4. Changing Educational Requirements

Another need for EBDM is reflected in educational requirements and competencies for both dental and dental hygiene students.

The ADA Accreditation Standards for Dental

Education Programs 36 explicitly state that dental schools must develop specific competencies that incorporate critical thinking and evidence-based skills and document that the care provided is evidence-based (Standards 2-9, 2-21 and

4

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

5-2).

36 In addition to the ADA, the American

Dental Education Association’s Competencies for the New Dentist identifies general skills that reflect an evidence-based approach.

37 These include being able to continuously analyze the outcomes of patient treatment to improve that treatment, evaluate scientific literature and other sources of information to make decisions about dental treatment, and manage oral health based on an application of scientific principles.

Similar competencies for dental hygienists are incorporated in the ADEA Dental Hygiene

Curriculum Guidelines.

38 For example, “The process of care requires defined problem solving and critical thinking skills and supports evidenced-based decision-making.” Further support for EBDM is found in the curriculum guidelines under Research for Dental and Dental

Hygiene Education (pp. 123-128) 38 in that their aims are to provide both dentists and dental hygienists with the skills and knowledge to be able to access the most recent and relevant scientific evidence, critically appraise it, and determine if it is applicable to the problem being addressed. The clear intent of the accreditation standards and competencies contained within these documents is the focus on the importance of comprehensive patient-centered care and the need for adding evidence-based decisionmaking to the traditional experienced-based approach. Table 1 highlights the four forces driving the need for EBDM.

Levels of Evidence

Sources regarded as strong evidence include clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews with meta-analyses, systematic reviews alone, individual randomized controlled trials (RCT), and well-designed non-randomized control studies (Figure 2). The hierarchy of evidence for treatment questions is based on the notion of causation and the need to control bias.

13,39

Although each level may contribute to the total body of knowledge, “...not all levels are equally useful for making patient care decisions.” 39 As you progress up the pyramid, the number of studies and correspondingly, the amount of available literature decreases, while at the same time their relevance to answering clinical questions increases (Figure 3).

39

Knowing which segment of the literature is appropriate for clinical decision-making and how to quickly retrieve this information is important

Figure 2. Study Types and Levels of Clinical Evidence

Modified Evidence Pyramid. Copyright permission granted by SUNY Downstate Medical Center,

Medical Research Library at Brooklyn

5

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

Table 1. The Need For EBDM to evidence-based practice. For example, the study methodology and level of evidence will differ based on the type of question asked, such as those derived from issues of therapy/ prevention, diagnosis, etiology, and prognosis.

Table 3 reviews the type of question and the highest levels of evidence based on the study methodology. For example, for questions associated with therapy and prevention, the highest level of evidence will be from metaanalyses or systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), since the objective of these studies is to test interventions demonstrating cause and effect and to select

Figure 3. Available Literature and its Relevance

Image: Available literature and its relevance.

6

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

treatments that improve the condition/disease and avoid adverse events.

9

Correctly identifying the type of study to answer the question is an important skill to develop in order to access the appropriate evidence when searching the healthcare literature. For example, identifying the best implant technique for replacing a single maxillary molar is a treatment question.

Ideally, a meta-analysis or systematic review of

RCTs would be available on the treatment being considered. If one were not available, then the next best evidence would be from a wellconducted individual RCT. However, when the focus of the question is on long-term outcomes of treatment, then it is a question of prognosis where the highest level of evidence would be provided by a systematic review of inception cohort studies, which are studies that follows patients from when a disease or condition first manifests itself clinically. And again, if a meta-analysis or systematic review were not available, the next highest level would be an individual inception cohort study, and so on down the hierarchy (Table

2). Two important concepts to keep in mind are that: 1) for any type of question, having a wellconducted meta-analysis or systematic review typically provides stronger evidence than a single study, and 2) a meta-analysis or systematic review is only as good as the individual studies that comprise it.

An excellent website that graphically displays the different types of research methods and designs can be found at the SUNY Downstate Medical

Center, Evidence Based Medicine Course, Guide to Research Methods - The Evidence Pyramid: http://library.downstate.edu/EBM2/2100.htm.

Evidence-Based Decision Making Skills and the 5-Step Process

The principles of EBDM methodology are based on the abilities to find, critically appraise, and correctly apply current evidence from relevant research to decisions made in practice so that what is known is reflected in the care provided. The EBDM skills and 5-step process are outlined in Table 3.

The following procedures provide an overview of the five steps and skills involved in establishing an evidence-based practice.

1. Converting information needs/problems into clinical questions so they can be answered – the PICO process.

Asking the right question is a difficult skill to learn, yet it is fundamental to evidence-based practice. The process almost always begins with a patient question or problem. A “well-built” question should include four parts, referred to as PICO that identify the Patient Problem or

Population (P), Intervention (I), Comparison

(C), and Outcome(s) (O).

2 These parts, or components provide the key terms for step two.

2. Conducting a computerized search with maximum efficiency for finding the best external evidence with which to answer the question.

This type of search requires a shift in thinking.

Often, especially now with fast web-based search engines, health professionals can look for “something” on a topic, a quick answer, or for “everything.” Finding relevant evidence requires conducting a focused search of the peer-reviewed professional literature based on the appropriate methodology. Online databases and software that enable quick access to the literature have made it easier to locate relevant clinical evidence.

43

Knowing what constitutes the highest levels of evidence and how to apply evidence-based filters and limits will let you search the literature with maximum efficiency. It is the combination of technology and good evidence that allows healthcare professionals to apply the benefits from clinical research to patient care.

43

To assist professionals in keeping up with the literature and in making it possible to quickly find needed information without leaving your location, online access to MEDLINE via

PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed, is provided by the National Library of Medicine

(NLM). See the dentalcare.com course,

Strategies for Searching the Literature Using

PubMed , for step-by-step guidance.

3. Critically appraising the evidence for its validity and usefulness (clinical applicability).

Once you have found the most current evidence, the next step in the EBDM process is

7

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

Table 2. Type of Question Related to Levels of Evidence and Study Methodology

8

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

Table 3. Skills needed to apply the EBDM Process 2 to understand what you have and its relevance to your patient and the PICO question.

Resources are available to help you critically appraise individual research studies and meta-analyses or systematic reviews. They consist of a worksheet with a structured series of questions that can help you determine the strengths and weaknesses of how a study was conducted and how useful and applicable the evidence is to the specific patient problem or question being asked.

44-46

4. Applying the results of the appraisal, or evidence, in clinical practice.

Once the methods are determined to be valid, the fourth step is to determine if the results, potential benefits or harms, are important. This is achieved by looking at whether there is an association between specific treatments and outcomes or exposures, the strength of that association, and the condition of interest, i.e., your patient problem or question. Understanding how to present statistical information to patients in a clear and unambiguous manner will help in making good patient care decisions.

Differences between groups in clinical trials are generally straight forward when expressed in terms of the mean values; whereas, results presented as proportions, such as relative risk reduction, absolute risk reduction, odds ratio and numbers needed to treat (NNT), are more challenging to understand. Also, understanding the difference between statistical and clinical significance will help you in translating and determining if the findings apply to your patient.

5. Evaluating the process and your performance

The final step in EBDM is evaluation of the effectiveness of the process. Mastering the skills of evidence based decision-making takes practice and reflection and a clinician who is new to the steps should not be discouraged by early difficulties encountered. Evaluating the process of EBDM may include a range of activities such as examining outcomes related to the health/function of the patient and patient satisfaction. Self-evaluation of developing skills is a most critical aspect in mastery of EBDM.

With an understanding of how to effectively use

EBDM, you can quickly and conveniently stay current with scientific findings on topics that are important to you and your patients.

Evidence-Based Decision-Making in

Action

The PICO Process (Skill/Step 1)

The formality of using PICO to frame the question forces the questioner to focus on what the patient/ client believes is the most important problem and the desired outcome. Doing this facilitates selecting language or key terms for conducting the computerized search, the second step in the process. Next, it allows you to determine the type of evidence and information required to solve the problem and the outcome measures that will be used to determine the effectiveness of the intervention.

One of the greatest difficulties in developing each aspect of the PICO question is providing an adequate amount of information without being too detailed. Each component of the PICO question

9

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

should be stated as a concise short phrase as illustrated in the following case example.

Case Example

Your new patient, Mr. Jim Logan, is a 48-year old marketing executive. His chief complaint is the/ discoloration of his front teeth, which he feels is getting worse as he gets older. He would like them to be as white as they were when he was

25 and even brought in a picture to show you.

He would like them whitened within one week before he attends his 30-year high school reunion.

When reviewing his health history and behaviors, you learn that Mr. Logan is a coffee drinker and recently stopped smoking. Upon examination, you determine his only treatment needs are preventive care and suggest you re-evaluate the discoloration after that appointment since the stain could be removed during his prophylaxis. If additional treatment is needed, you can make him custom trays for use with an at-home whitening/ bleaching system, which is safe and will meet his time requirement.

You present the bleaching procedure options and related fees to Jim. He questions you about the differences between laser bleaching and Crest

Whitestrips™ that do not require a tray and can be purchased at the local grocery store. He would like to know if the whitening strips are just as effective especially since is cost considerably less.

You are not familiar with the latest scientific literature on the whitening strips to answer Mr.

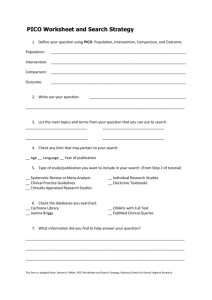

Logan’s questions thoroughly and will be glad to investigate the Whitestrips option so each of you are fully informed about the pros and cons before selecting a treatment. With the popularity of these treatment options and new products introduced quite frequently, this information will be a valuable addition to the evidence-based “library” you are creating in your office. To find the answer, you must define Jim’s question so it facilitates an efficient search of the literature. To guide this process, the PICO Worksheet and Search

Strategy form can assist you (Table 4).

Applying the PICO Process

The first step in developing a well-built question is to identify the patient problem or population [P] by describing either the patient’s chief complaint or by generalizing the patient’s condition to a larger population. The problem is further shaped or refined by the most important characteristics that might influence the results such as:

• Level of disease or health status

• Age, race, gender, previous conditions, past and current medications

In Mr. Logan’s case, we know the chief complaint is discoloration of his front teeth and that coffee and tobacco are contributing factors. So, in addition to the chief complaint, age, and current habits, previous behaviors may influence the decision as to which treatment might be most appropriate.

Identifying the Intervention [I] is the second step in the PICO process. It is important to identify what you plan to do for that patient. This may include the use of a specific diagnostic test, treatment, adjunctive therapy, medication, or the recommendation to the patient to use a product or procedure. The intervention is the main consideration for that patient.

4 In Mr. Logan’s case, the intervention being considered is the

Crest Whitestrips™ since he has specifically asked about them. This also keeps the process patient-centered.

The third phase of the well-built question is the

Comparison [C], which is the main alternative

(intervention) you are considering.

2 It should be specific and limited to one alternative choice, usually the gold standard, in order to facilitate an effective computerized search. The Comparison is the only optional component in the PICO question since there may not be an alternative, however when there is one, it should be used. In our case, we have selected the custom trays for at-home bleaching as the main alternative.

The final aspect of the PICO question is the outcome [O]. This specifies the result(s) of what you plan to accomplish, improve, or affect, and it should be measurable. Examples of outcomes are relieving or eliminating specific symptoms, improving or maintaining function, and enhancing esthetics. In Mr. Logan’s case, you are seeking evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of the whitening/bleaching treatment under a given set of conditions, i.e., effective in whitening his teeth within one week so they appear as white as they were when he was 25 years old. Outcomes yield

10

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

Table 4. PICO Worksheet for Mr. Logan’s Case

PICO Worksheet for Mr. Logan's Case

1. Define your question using PICO by identifying: Problem, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes.

Your question should be used to help establish your search strategy.

Patient/Problem________________________________

Intervention___________________________________

Comparison___________________________________

Outcome______________________________________

2.

Write out your question:_______________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

3.

Type of question/problem: Circle one:

Therapy/Prevention Diagnosis Etiology Prognosis

4.

Type of study (Publication Type) to include in the search: Check all that apply:

Meta-Analysis

Clinical Trial

Cohort Study

Systematic Review

Practice Guideline

Case Control Study

Editorials, Letters, Opinions

Animal Research

Randomized Controlled Trial

Literature Review

Case series or Case Report

In Vitro/Lab Research

5.

List main topics and alternate terms from your PICO question that can be used for your search

List your inclusion criteria – gender, age, year of publication, language

List irrelevant terms that you may want to exclude in your search

List where you plan to search, i.e., MEDLINE, PubMed, EBM Reviews-Cochrane Database,

CINAHL

© 2001 SA Miller, PICO Worksheet

National Center for Dental Hygiene Research

11

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

better search results when defining them in specific terms and they should solve the specific problem.

“ More effective or just as effective ” are not acceptable outcomes unless they describe how the intervention is more effective or just as effective.

For our example, just as effective in whitening teeth within one week is the desired outcome.

Structuring the PICO Question

After understanding the elements of PICO and identifying the patient’s concerns, you are now ready to structure the PICO question for Mr. Logan’s case.

P = Patient Problem or Population

The first part of the PICO question begins with the following phrase: For a patient with...

Inserting the patient’s chief complaint or condition completes this phrase. For Mr. Logan, this phrase can be completed as follows:

“ For a patient with tooth discoloration due to coffee and tobacco ”.

I = Intervention

The main intervention being considered is Crest

Whitestrips™, so the question now reads:

“ For a patient with tooth discoloration due to coffee and tobacco, will Crest Whitestrips ”.

C = Comparison

The comparison phrase is stated “as compared to” the main alternative, which in this case is custom trays for use with an at-home whitening/bleaching system. The question now reads:

“ For a patient with tooth discoloration due to coffee and tobacco, will Crest Whitestrips, as compared to custom trays for use with an at-home whitening bleaching system ”.

O = Outcome(s)

Mr. Logan’s main concern is the discoloration of his teeth and having his teeth as white as they were when he was 25 years old within a 1 week period. The outcome(s) is then phrased as, be as effective in whitening his teeth within 1 week.

Based on these four parts, the complete PICO question can be stated as:

“ For a patient with tooth discoloration due to coffee and tobacco, will Crest Whitestrips, as compared to custom trays for use with an at-home whitening bleaching system, be as effective in whitening his teeth within 1 week?

”

Following the PICO Worksheet (Table 5), you would then identify the type of question and study and then list any additional terms or phrases related to the already identified P , I , C , and O . By generating these words, alternative key terms are identified that facilitate finding evidence to answer your question, Step 2, conducting a computerized search with maximum efficacy, in the EBDM process. For example, key terms that could be used in the search are ‘tooth bleaching’ or ‘tooth whitening’ or ‘Crest Whitestrips’ or ‘whitening strips’ or ‘hydrogen peroxide’ or ‘carbamide peroxide.’ An example of a completed PICO Worksheet for Mr.

Logan’s case is shown in Table 5.

Benefits of EBDM

EBDM provides a strategy for improving the efficiency of integrating new evidence into patient care more rapidly by helping you manage an increasing amount of information. EBDM assists you in developing treatment plans and providing treatment and advice that are scientifically defensible. In addition, it helps insure that your practice is continually informed and strengthened by current research findings, helping to close the gap between what is known (research evidence) and what is practiced.

EBDM is not about knowing all the answers, but rather about knowing how to structure good questions to be able to find relevant information to better inform your decision making, and how and when to integrate new thinking and action into everyday practice.

Conclusion

Recognizing that clinicians have time constraints and yet want to provide the best possible care to their patients, an evidence-based approach offers clinicians a convenient method of finding current research to support clinical decisions, answer patient questions, and explore alternative treatments, procedures, or materials. With an understanding of how to effectively use EBDM, practitioners can quickly and conveniently stay current with scientific findings on topics that are important to them and their patients.

12

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

Table 5. Completed PICO Worksheet for Mr. Logan’s Case

Completed PICO Worksheet for Mr. Logan's Case

1. Define your question using PICO by identifying: Problem, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes.

Your question should be used to help establish your search strategy.

Patient/Problem: Tooth discoloration due to coffee and tobacco stain

Comparison: Custom trays for at-home whitening/bleaching system

Outcome: Effective in whitening his teeth within 1 week

2.

Write out your question: For a patient with tooth discoloration due to coffee and tobacco, will

Crest Whitestrips, as compared to custom trays for use with an at-home whitening/bleaching system, be as effective in whitening his teeth within 1 week?

3.

Type of question/problem: Circle one:

Therapy/Prevention Diagnosis Etiology Prognosis

4.

Type of study (Publication Type) to include in the search: Check all that apply:

:

Meta-Analysis

:

Systematic Review

:

Randomized Controlled Trial

:

Clinical Trial

Cohort Study

Practice Guideline

Literature Review

Case Control Study

Editorials, Letters, Opinions

Animal Research

Case series or Case Report

In Vitro/Lab Research

5. List main topics and alternate terms from your PICO question that can be used for your search

Crest Whitestrips Tooth whitening

Whitening strips

Custom tray whitening/bleaching

Night guard bleaching

Tooth bleaching

Carbamide peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide

List your inclusion criteria – gender, age, year of publication, language

English

1990 - present

Human subjects

List irrelevant terms that you may want to exclude in your search

Whitening dentifrice

Whitening toothpaste

Whitening mouthrinse

List where you plan to search, i.e., MEDLINE, PubMed, EBM Reviews-Cochrane

Database, CINAHL

PubMed

MEDLINE

EBM Reviews-Cochrane Database

© 2001 SA Miller, PICO Worksheet

National Center for Dental Hygiene Research

13

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

Course Test Preview

To receive Continuing Education credit for this course, you must complete the online test. Please go to: www.dentalcare.com/en-us/dental-education/continuing-education/ce311/ce311-test.aspx

1. The following components define evidence-based practice: a. Clinical expertise b. Patient values c. Scientific research d. Clinical conditions e. All of the above.

2. The purpose of EBDM is to _______________.

a. emphasize new research findings b. close the gap between research and practice c. defer to patients wishes d. use expert opinions e. None of the above.

3. EBDM is just a new term for clinical decision-making.

a. True b. False

4. EBDM requires online searching skills and understanding research methods.

a. True b. False

5. Evidence can change over time as new research studies are conducted.

a. True b. False

6. The highest level of evidence is the same for treatment and prognosis questions.

a. True b. False

7. Which of the following provides the highest level of evidence for treatment questions?

a. Case Control Study b. Cohort Study c. Systematic Review of RCTs d. Randomized Controlled Trial e. Case Report

8. Systematic reviews typically provide a higher level of evidence than a single study.

a. True b. False

9. As you progress up the levels of evidence, the amount of available literature also increases.

a. True b. False

14

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

10. As you progress up the levels of evidence, the literature becomes more relevant for answering therapy related questions.

a. True b. False

11. The first step in the EBDM process is _______________.

a. finding the best evidence b. applying the results to patient care c. asking a good clinical question d. evaluating the results e. critically appraising the evidence

12. Which of the following characteristics describes the Intervention in the PICO process?

a. What you plan to do.

b. Main concern or chief complaint.

c. Measurable result.

d. Alternative.

13. The only optional component of the PICO question is _______________.

a. P (Patient Problem or Population) b. I (Intervention) c. C (Comparison) d. O (Outcomes)

14. The purpose of defining the PICO question is to _______________.

a. identify a clearly focused clinical question b. consider what the patient/client believes is important c. provide key search terms d. determine the type of evidence required to solve the problem e. All of the above.

15. Select the most appropriate PICO question: a. Is using Mouthwash ‘x’ as effective as flossing in reducing gingivitis?

b. For a patient with mild gingivitis, is Mouthwash ‘x’ as compared to flossing as effective?

c. For a patient with mild gingivitis, is rinsing with Mouthwash ‘x’ as compared to flossing as effective in reducing plaque and eliminating gingivitis?

d. For a patient with mild gingivitis, is rinsing with Mouthwash ‘x’ as effective in reducing plaque and eliminating gingivitis as flossing?

e. None of the above.

16. Select the PICO component that is missing or incomplete from this question: For a patient with periodontal disease, will antimicrobial therapy (minocycline HCl) in conjunction with scaling and root planing be more effective in preventing further attachment and bone loss?

a. P (Patient Problem or Population) b. I (Intervention) c. C (Comparison) d. O (Outcomes)

15

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

17. Benefits of the EBDM process include: a. Provides a strategy for improving the efficiency of integrating new research evidence into patient care more rapidly by helping you manage an increasing amount of information.

b. Assists in developing treatment plans and providing treatment and advice that are scientifically defensible.

c. Helps insure that practice is continually informed and strengthened by current research findings.

d. All of the above.

e. A and C

16

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

References

1. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992 Nov 4;268(17):2420-2425.

2. Straus SE, Glasziou P, Richardson WS, Haynes RB. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and

Teach It, 4th Ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2011.

3. American Dental Association. Professional Issues and Research, ADA Guidelines, Positions and

Statements, ADA Policy on Evidence-based Dentistry. 2002.

4. Eisenberg J. Statement of health care quality before the house subcommittee on health and the environment, 10/28/97. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Archive 97 A.D.

5. Haynes RB. Some problems in applying evidence in clinical practice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993 Dec 31;

703:210-224.

6. Institute of Medicine. Dental education at the crossroads, challenges and change. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press, 1995.

7. Davidoff F. In the teeth of the evidence: the curious case of evidence-based medicine. Mt Sinai J Med.

1999 Mar;66(2):75-83.

8. Davidoff F, Case K, Fried PW. Evidence-based medicine: why all the fuss? Ann Intern Med. 1995 May 1;

122(9):727.

9. Evidence-based Medicine Working Group (Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade, MO, Cook DJ Editors). Users’

Guides to the Medical Literature, A Manual for EB Clinical Practice, 2nd Edition. Chicago: AMA, 2008.

10. Palmer J, Lusher A, Snowball R. Searching for the evidence. Genitourin Med. 1997 Feb;73(1):70-72.

11. Greco PJ, Eisenberg JM. Changing physicians’ practices. N Engl J Med. 1993 Oct 21;329(17):1271-1273.

12. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. Undertaking Systematic Reviews of

Research on Effectiveness. University of York website. 1997. Accessed September 9, 2004.

13. Long A, Harrison S. The balance of evidence. Evidence-based decision making. Health Services Journal,

Glaxo Welcome Supplement 1995;6:1-2.

14. Bader JD, Shugars DA. Variation in dentists’ clinical decisions. J Public Health Dent. 1995 Summer;

55(3):181-188.

15. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, IOM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health

System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: The National Academy of Sciences, 2000.

16. Verdonschot EH, Angmar-Månsson B, ten Bosch JJ, Deery CH, Huysmans MC, Pitts NB, Waller E.

Developments in caries diagnosis and their relationship to treatment decisions and quality of care. ORCA

Saturday Afternoon Symposium 1997. Caries Res. 1999;33(1):32-40.

17. Bader JD, Shugars DA. Variation, treatment outcomes, and practice guidelines in dental practice. J Dent

Educ. 1995 Jan;59(1):61-95.

18. Ecenbarger W. How honest are dentists? Reader’s Digest, February 1997. 50-56.

19. Bogacki RE, Hunt RJ, del Aguila M, Smith WR. Survival analysis of posterior restorations using an insurance claims database. Oper Dent. 2002 Sep-Oct;27(5):488-492.

20. Yingling NM, Byrne BE, Hartwell GR. Antibiotic use by members of the American Association of

Endodontists in the year 2000: report of a national survey. J Endod. 2002 May;28(5):396-404.

21. Epstein JB, Chong S, Le ND. A survey of antibiotic use in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 Nov;

131(11):1600-1609.

22. Anderson G, Allison D. Intrapartum electronic fetal heart rate monitoring: A review of current status for the Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Preventing Disease. Beyond the Rhetoric. New York:

Springer-Verlag, 1990: 19-26.

23. Crowley P, Chalmers I, Keirse MJ. The effects of corticosteroid administration before preterm delivery: an overview of the evidence from controlled trials. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990 Jan;97(1):11-25.

24. Frazier P, Horowitz A. Prevention: A public health perspective. Oral Health Promotion and Disease

Prevention. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaard, 1995.

25. Grimes DA. Graduate education. Evidence-Based Medicine 1995; 86(3):451-457.

26. Selwitz RH, Winn DM, Kingman A, Zion GR. The prevalence of dental sealants in the US population: findings from NHANES III, 1988-1991. J Dent Res. 1996 Feb;75 Spec No:652-660.

27. Healthy People 2010. Oral Health Section, #21. Accessed January 21, 2008.

17

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

28. Gravois SL, Bowen DM, Fisher W, Patrick SC. Dental hygienists’ information seeking and computer application behavior. J Dent Educ. 1995 Nov;59(11):1027-1033.

29. Covington P, Craig BJ. Survey of the information-seeking patterns of dental hygienists. J Dent Educ. 1998

Aug;62(8):573-577.

30. Schleyer TK, Forrest JL, Kenney R, Dodell DS, Dovgy NA. Is the Internet useful for clinical practice?

J Am Dent Assoc. 1999 Oct;130(10):1501-1511.

31. Ramsey PG, Carline JD, Inui TS, Larson EB, LoGerfo JP, Norcini JJ, Wenrich MD. Changes over time in the knowledge base of practicing internists. JAMA. 1991 Aug 28;266(8):1103-1107.

32. Forrest JL, Horowitz AM, Shmuely Y. Caries preventive knowledge and practices among dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2000 Summer;74(3):183-195.

33. Yellowitz JA, Horowitz AM, Drury TF, Goodman HS. Survey of U.S. dentists’ knowledge and opinions about oral pharyngeal cancer. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 May;131(5):653-661.

34. Forrest JL, Drury TE, Horowitz AM. U.S. dental hygienists’ knowledge and opinions related to providing oral cancer examinations. J Cancer Educ. 2001 Autumn;16(3):150-156.

35. Niederman R, Chen L, Murzyn L, Conway S. Benchmarking the dental randomized controlled literature on

MEDLINE. EBD 2002; 3:5-9.

36. American Dental Association Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental

Education Programs. Chicago: ADA, 2010, pp. 12-13, 24, 28, and 35.

37. ADEA Competencies for the New General Dentists (As approved by the ADEA House of Delegates on

April 2, 2008). Accessed March 1, 2014.

38. American Dental Education Association. Compendium of Curriculum Guidelines (Revised Edition) for

Allied Dental Education Programs. ADEA website 2005;123-128. Accessed March 1, 2014.

39. McKibbon A, Eady A, Marks S. PDQ, Evidence-Based Principles and Practice. Hamilton, Ontario: B.C.

Decker Inc., 1999.

40. Phillips B, Ball C, Sackett D, Badenoch D, Straus S, Haynes RB et al. Updated by Jeremy Howick, Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendations. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2009. Accessed

January March 1, 2014.

41. Duke University Medical Center Library, Health Sciences Library University of North Carolina at Chapel

Hill. Introduction to Evidence-Based Medicine, The Well-build Clinical Question. Duke University Medical

Center Library and Health Sciences Library University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Accessed January

22, 2008.

42. Rosenberg W, Donald A. Evidence based medicine: an approach to clinical problem-solving. BMJ. 1995

Apr 29;310(6987):1122-1126.

43. Haynes RB, Wilczynski N, McKibbon KA, Walker CJ, Sinclair JC. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound studies in MEDLINE. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994 Nov-Dec;1(6):447-458.

44. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 10 Questions to help make sense of the literature. CASP Institute of

Health Sciences. Public Health Resources Unit. Accessed March 1, 2014.

45. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001 Apr 14;357(9263):1191-1194. Accessed

March 1, 2014.

46. PRISMA. Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Accessed March 1, 2014.

18

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014

About the Author

Jane L. Forrest, EdD, BSDH

Dr. Forrest is the Chair of the Behavioral Science Section in the Division of Dental Public

Health & Pediatric Dentistry, and the Director of the National Center for Dental Hygiene

Research and Practice at the Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, CA. Dr.

Forrest has received federal funding for several grants including one to prepare faculty on how to integrate an evidence-based approach into curriculum. As part of that grant, the

Evidence-Based Decision Making website was established (http://www.usc.edu/ebnet).

Dr. Forrest is an internationally recognized author and presenter on Evidence-Based

Decision Making (EBDM). She has served as the pre-Conference workshop chair for both the First and

Second International Conferences on Evidence-Based Dentistry and has participated in the ADA’s Champion

Conferences on EBD. Dr. Forrest is the lead co-author on a new book, Evidence-Based Decision

Making: A Translational Guide for Dental Professionals and has chapters published on EBDM in Clinical

Periodontology and Dental Hygiene Concepts, Cases and Competencies .

Dr. Forrest serves on several editorial boards and as an Associate Editor for the Journal of Evidence-Based

Dental Practice.

Email: jforrest@usc.edu

19

Crest ® Oral-B ® at dentalcare.com Continuing Education Course, Revised April 7, 2014