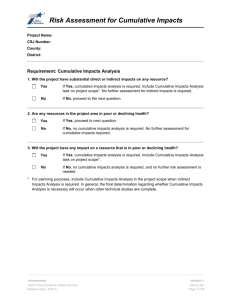

Legal Sufficiency Criteria for Adequate Indirect Effects and

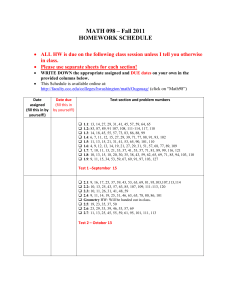

advertisement