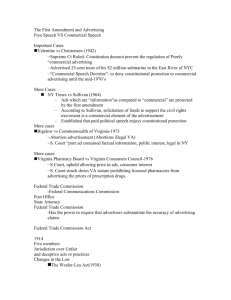

Federal Trade Commission Regulation of Food Advertising to

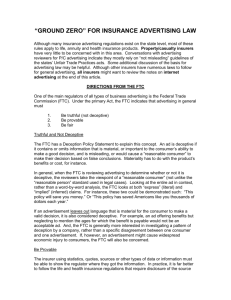

advertisement