CHAPTER 12:

advertisement

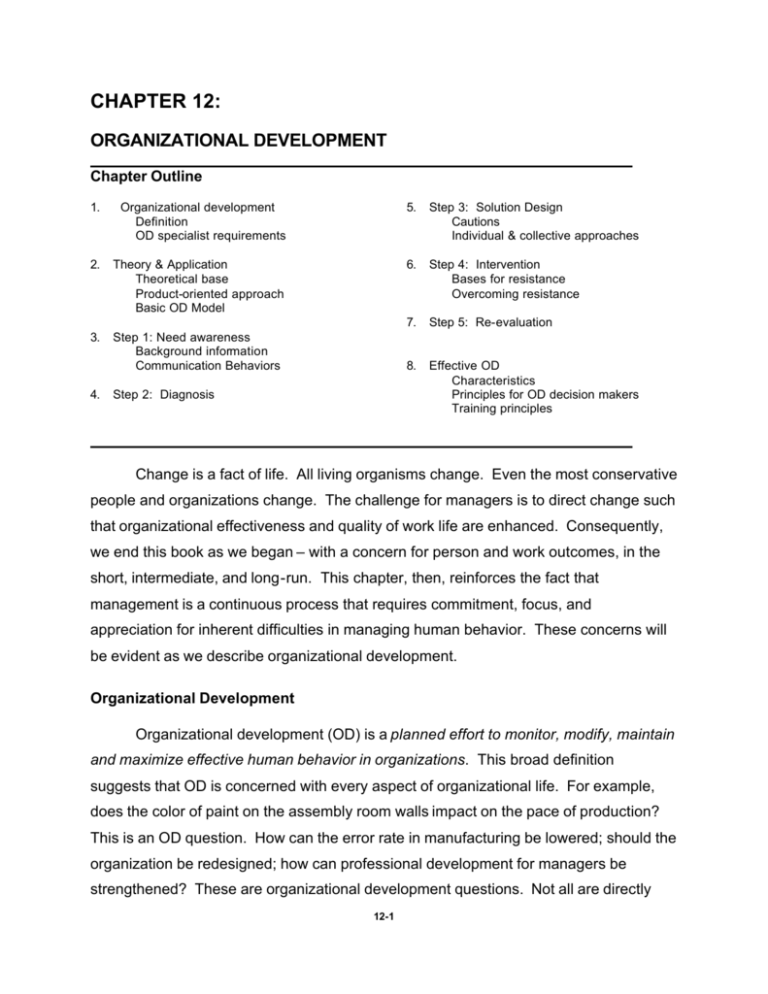

CHAPTER 12: ORGANIZATIONAL DEVELOPMENT Chapter Outline 1. Organizational development Definition OD specialist requirements 5. Step 3: Solution Design Cautions Individual & collective approaches 2. Theory & Application Theoretical base Product-oriented approach Basic OD Model 6. Step 4: Intervention Bases for resistance Overcoming resistance 7. Step 5: Re-evaluation 3. Step 1: Need awareness Background information Communication Behaviors 8. Effective OD Characteristics Principles for OD decision makers Training principles 4. Step 2: Diagnosis Change is a fact of life. All living organisms change. Even the most conservative people and organizations change. The challenge for managers is to direct change such that organizational effectiveness and quality of work life are enhanced. Consequently, we end this book as we began – with a concern for person and work outcomes, in the short, intermediate, and long-run. This chapter, then, reinforces the fact that management is a continuous process that requires commitment, focus, and appreciation for inherent difficulties in managing human behavior. These concerns will be evident as we describe organizational development. Organizational Development Organizational development (OD) is a planned effort to monitor, modify, maintain and maximize effective human behavior in organizations. This broad definition suggests that OD is concerned with every aspect of organizational life. For example, does the color of paint on the assembly room walls impact on the pace of production? This is an OD question. How can the error rate in manufacturing be lowered; should the organization be redesigned; how can professional development for managers be strengthened? These are organizational development questions. Not all are directly 12-1 related to communication, but, in many cases, outcomes may be heavily dependent on communication effectiveness. Successful OD specialists tend to possess two characteristics. First, they spend a lot of time asking “why” a particular set of outcomes exists. Essentially, they are very concerned about differentiating between a “problems” symptoms and causes (consistent with concern we expressed in chapter 6, problem/solutions identification). Second, they understand the relationship between theory and practice. Theory & Practice Often, tension exists between the theoretician or academic and those who practice in non-academic settings. The practitioner often views the academic as having little “real” world experience and regards that perspective (theoretic) as ethereal. In contrast, many academics frequently view practitioners as shortsighted and focused on the bottom-line. Both perspectives are extreme and contain stereotypic inaccuracies. In reality, theory and practice go hand-in-hand. In other words, a “good” theory, by definition, must provide guidance for good practice. And, we have yet to find a “good” practice that is not supported by theory. Hence, theory and practice are important and inseparable. Theoretical base. Theoretically, many communication specialists have failed to provide a useful conceptual scheme for explaining communication activity. As a result, they provide vague, often inconsistent, notions of what they study and view everything as being directly related to communication. They fall into the error described by an old cliché: “When something is everything, then it is nothing.” Such is the case of those who view communication as synonymous with human behavior. Others believe defining communication is a mere classroom exercise and have never personally struggled with its boundaries. Both perspectives produce OD specialists that meddle in every aspect of organizational behavior, including the color of paint on the walls. Often, employees may have a philosophical prejudice that must be dealt with. This prejudice is that anything theoretical is not practical. Too often, one hears students 12-2 and managers exclaim, “I don’t want theory; I want something practical!” However, both are inseparable; they feed on each other. Theoretical knowledge guides the questions the OD specialist asks, problems identified, solutions designed, and implementation methods. In short, theory provides the framework for practice. At the same time, “hands-on” experience nourishes theory. The workplace provides a field of study and testing place for theories. Without this understanding and appreciation, OD efforts become fragmented and aimless. Product -oriented approach. Application provides the test for theory and is a measure of the theory’s usefulness. Essentially, a product-oriented approach is concerned with defining specific actions for achieving short-, intermediate, and long-run goals – i.e., what things can I do to improve satisfaction, productivity, adapta tion, development, and survival. Thus, there is emphasis on concrete, observable, and tangible actions that have a measurable outcome. Yet, the range of available alternatives and predictions of successful outcomes are most often predicated on preexisting theoretical formulations. With the assumption of theory and Organizational Development Cycle of Events practice complementing 1. Need Awareness one another, we now proceed to a description of the 5 steps of OD: 5. Reevaluate 2. Diagnosis need awareness, diagnosis, solution design, intervention, and re- 4. Intervention 3. Solution Design evaluation. Step 1: Need Awareness Initially, some stimulus creates an awareness of the need to develop. This may take the form of unacceptable productivity, a series of complaints, a desire to innovate, 12-3 high absenteeism, or the realization that some part of the organization is outmoded. This pressure triggers the first step in an OD sequence. Need awareness is an orientation phase, similar to problem identification (chapter 6). During this phase, two general actions should take place: gather background information and systematically determine communication behaviors. Background information. Initially, information must be gathered from those who perceive a need for change. It is important to gather data from a variety of perspectives, particularly in term of goals and how the need for change is related to goals. Issues discussed in chapters 1, 2, 3, and 4 are particularly useful here. Production, maintenance, supportive, adaptive, and managerial subsystems can be described and evaluated in terms of how they interact with each other. The organization can be plotted on the Communication Design Matrix and compared to the organizational design being used, etc. If you are an external consultant (from outside the organization; sometimes referred to as a change agent in diffusion literature), this is the time to become familiar with operations in all affected subsystems/departments. Examine the organization’s history, past development efforts, reports by consultants, structure and design, etc. When appropriate, request to be introduced at staff meetings so that all affected parties are aware that development activity will be taking place. This helps manage negative aspects of rumors that often accompany the presence of a consultant. Communication behaviors. Chapters 5, 6, 7, and 8 provided guidelines for “fine tuning” organizations through the use of communication functions. These provide the basis for examining communication behaviors and assist in moving to “diagnosis.” It is important to emphasize, however, members of the organization often label problems as “communication” problems. This would lead to a communication solution. However, quite frequently, communication is “symptom” and not the cause of a problem. Hence, be cautious about over-reliance on communication solutions. 12-4 Examination of communication behavior should proceed from a theory base. For example, when applying the functional theory of communication, a thorough, systematic method for asking questions emerges: 1. What is the relationship between communication behavior and organizational design; what is the goodness of fit between employees and their job/communication roles? (Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4) 2. What are the ways employees and the organization manage and exchange information; what are the strengths and weaknesses? (Chapter 5) 3. What are the ways employees and the organization identify problems and solutions; what are the strengths and weaknesses? (Chapter 6) 4. What are the ways employees and the organization manage and regulate behavior; what are the strengths and weaknesses? (Chapter 7) 5. What are the ways employees and the organization manage conflicts; what are the strengths and weaknesses? (Chapter 8) 6. What are the ways employees and the organization “talk” about work; what motivation strategies are used; what is the level of satisfaction and quality of work life; what is the level of productivity; what are the strengths and weaknesses in these areas? (Chapters 9, 10, 11) These questions have been written in very general terms. Their primary purpose is to isolate a general dimension of communication and organizational activity. Each general area provides boundaries and directions for more extensive investigation. Furthermore, the questions are based upon key issues discussed in previous chapters. Once you have isolated a general area, you can refer the associated book chapter for guidelines to conduct a more in-depth analysis. In summary, need awareness occurs because someone has recognized change is desirable. This might happen because problems are perceived or simply because 12-5 improvement is sought. This leads to actions that include gathering background information, defining communication behavior, and separating causes and symptoms. Step 2: Diagnosis Diagnosis must begin with a theory base that contains concepts and variables useful for applying to the organization. For example, the first 4 chapters emphasized the usefulness of Katz and Kahn’s organizational subsystems (production, maintenance, supportive, adaptive, managerial) in diagnosing operations, comparing organizations, and discovering potential areas for improvement. There are several other theoretical models you may wish to use, contingent on your unit of analysis. Some theories are suitable for individuals, some for groups, and some for entire organizations. The critical decision, however, is defining the unit of analysis. If you were thorough in Step 1, this shouldn’t be problematic. There is no such thing as “the correct perspective.” All tested theories have their place. You may use a combination of them in your diagnosis. Remember, there is no single “catholic” and universal theory of human and organizational behavior. In other words, you may need more than one theory base. Beware of the “law of the hammer” – or, pounding every issue into the same shape and looking at it from only one perspective! This is very limiting. Unfortunately, many contemporary theories become “popularized” and come into vogue. Then, they are immediately seized and applied by zealots of the approach, even when they are not needed or inappropriate. During the diagnostic step, the aim is to identify specific needs and articulate them as concretely as possible. For example, problems with information management may be the general area isolated in Step 1. But, this is too general to take action on. The statement should be very specific, like: “information is being distorted by production line A because they are in intense competition with production line B; the organization relies solely on e-mail to exchange information and provides little opportunity for face-to-face interaction.” After developing a specific list of needs, you are ready to move to Step 3. 12-6 Step 3: Solution Design Cautions. As you move to Step 3, it is important to pay heed to several cautions. First, the existence of a problem does not imply the existence of a “ready made” solution. If problems were easy to fix, there would be no need for an OD specialist. Second, avoid developing or having a favorite solution that yo u constantly seek a problem for. During the 1980’s and 1990’s, consultants became enamored with “Total Quality Management” and “Continuous Quality Improvement” approaches. And, across the United States, organizations were jumping on the TQM/CQI bandwagon. Today, you hear those terms infrequently. Why? In most cases their application was not the consequence of thorough need awareness and diagnosis steps. Here, the “law of the hammer” was used. And, in most cases the programs failed. The approach, however, is sound – but it is only appropriate for certain conditions. Third, avoid innovation bias. There is a network of OD specialists who share information about new approaches and trends in development. There is often “pressure” to adopt the latest approaches, even though they may not be needs. Such was the case for TQM. Fourth, few quick fixes work. The true test is for specialists to learn how to apply knowledge in creative ways as new situations arise. Individual & collective approaches. We began this book by contrasting psychological and sociological approaches for explaining human behavior. Here, we conclude the book by revisiting this comparison. Ultimately, some solutions are better for individuals (psychological) and some work best with groups (sociological). The table below provides a description of some individual and collective (group) solution designs: 12-7 Individual Level Collective Level Training programs. Carefully planned instructional sessions designed to highlight one or two critical activities. They often use lecture, discussion, role playing, experiential &/or simulation exercises, and case studies Counseling. 1 on 1 interview sessions where the specialist dissects a particular activity of the interviewee. Problems and solutions are identified and a plan for implementation is developed Team building. This is a popular approach that brings a work group or team together in a special setting to define a process, identify weaknesses or areas to improve, and develop a plan or method to improve the process. Observer intervention. The specialist observes a group in their normal work setting and makes on the spot suggestions for improvement (a significant amount of observation happens first). Group analysis survey. A survey is developed to investigate and measure strengths and weaknesses. All members participate in the survey. Groups use survey data to define problems and solutions that will be implemented. Confrontational meeting. (Developed by Beckhard, 1967) The procedure brings groups of peers together to discuss issues. After problems are identified, supervisors are included. Then, solutions are created. Organizational design. This requires an actual change in organizational structure. Often, this is done to improve the adaptive subsystem processes by enhancing information exchange among those who need the other’s information. T-groups/sensitivity training. While this process involves a group, the emphasis is on helping the individual become more sensitive to others’ needs. Effectiveness depends on willingness to participate over an extended period of time. Performance appraisal. Evaluation of an individual’s performance, strengths, and weaknesses, based upon a’ priori developed set of criteria. The appraisal provides the basis for goal setting. On the job training/OJT. This specific training is directly related to an individual’s job role and takes place at the work location. Typically, the supervisor performs the role of “trainer.” This is basically “learning by doing.” The list of individual and collective techniques is much longer than we provide here. As an OD specialist, you will refer to many other publications and discussions of change solutions. What is important is that you select solutions that are appropriate, particularly in terms of a thorough diagnosis, constraints on organizational resources, and constraints on you, the OD specialist. After these considerations are made, it is time to consider intervention. Step 4: Intervention Some suggest that intervention begins the moment an OD specialist is called onto the scene (Step 1). Although there is some truth to this assertion, intervention actually begins when the specialist initiates a solution designed to meet a particular need. During the first 3 steps, the specialist listened, asked questions, collected information, and designed solutions. The specialist’s presence probably had some 12-8 ancillary impact on the organization, but a skilled specialist can minimize the potential for negative consequences. Employees develop a level of comfort in their roles. As a result intervention, i.e., change, is often resisted. Being aware of the following causes of resistance to change permits development of strategy to reduce resistance: Potential Causes for Resistance to intervention Perceived threat. The most common source of resistance results from the human tendency to feel nervous about the unknown. Most persons are uncomfortable in new situations; they tend to wonder if changes will have a negative impact on them personally. As a result, they react defensively to solutions that impact on their “territory.” Suspicion. There is often a strong suspicion among employees that the OD specialist usually has little impact. Others may suspect the specialist’s intentions are not in their interest. The unfortunate part of suspicion is that some specialists do poor work and reinforce the suspicions. This form of resistance affects the credibility of all specialists and creates resistance toward skilled specialists. Intervention at the wrong level. Resistance and frustration often result from attempts to implement solutions at the wrong level or within the incorrect system. In addition, it is difficult to be successful if top management has not publicly supported development activity. Without publicly stated support and necessary resources, the intervention will eventually fail. Too much change. A common principle in research literature about persuasion is that people cannot make many large, sustained changes in a short period of time. Plus, when individuals perceive a solution as “radical” and having a short time for implementation, resistance will escalate even further. Change is poorly explained. Learning theorists know that learning something new is a complicated process. Solutions that may seem very simple to the specialist may be perceived as complicated by the target of change. A common complaint is that solutions are too “theoretical.” This charge often means that employees simply don’t understand the logic of a solution. Sometimes, however, specialists find it difficult to explain the logic of change in a way that the employee will understand. Once the specialist is aware of the causes of resistance, then it becomes easier to develop techniques that will reduce resistance. Specific techniques include: don’t be self-centered, intervene at the proper level, allow employees to participate in the development process, design changes in small increments, and continually monitor and adapt: 12-9 Some Techniques for Reducing Resistance to Change Avoid self-centeredness --Sometimes, specialists become so convinced that they have the right solution that they tend to ignore others’ points of view. This self-centeredness is a barrier to effective change. Intervene at proper level -- It is also critical that the primary unit of analysis be defined. Once this is done, it is much easier to identify the subsystem targets of change. Allow employee participation -- Employee participation in change enables a feeling of “ownership” and stimulates desire to change. Furthermore, as employees are involved the likelihood for specialist self-centeredness is reduced. Design change in small increments -- Individuals and groups are more will to make large changes in small steps than to make large changes in 1 or 2 big steps. Monitor & adapt -- It is important to monitor the consequences of change at each step. This enhances flexibility and allows modification when needed. If solutions are not producing expected results, the specialist must make adjustments. Diagnosis of problems and prescription of effective solutions are not exact sciences, so the specialist must monitor, adapt, and re-evaluate as necessary. Step 5: Re-evaluation The OD specialists work isn’t over when change is introduced. The process we have described here ends with evaluation, which causes a movement back to Step 1 (i.e., to see if a need exists to change or maintain). Effective Organizational Development Characteristics. The five-step cycle of events outline the process of organizational development. In order for an organization to exhibit dynamic homeostasis and acquire negentropy, OD must be a never ending, continuous activity. In addition, effective OD is characterized by these characteristics: it is supportive of people with different points of view; (2) it functions as a training model for employees; (3) it is simple enough to be used by managers who continually monitor the work area (Levinson, 1972). In addition, effective programs have an inherent feedback mechanism for the change target, i.e., provides the individual with information about how they are doing and the effects of change. Underlying these characteristics of effective change is the assumption of flexibility and adaptability. A successful change in one system may not work in another without modification. 12-10 Principles for OD decision makers & Training. Throughout this book, we have made it a point to provide practical application statements in the form of principles. We end the book with the same approach. Based on research and experience, we have identified 5 important, general principles that OD specialist should follow (these are derived from the topics we have covered throughout the book: Principles for OD Decision Makers 1. Avoid the assumption that all problems stem from a previously discovered cause. Refer to problem/solution identification techniques in chapter 6. 2. Ensure adequate information is gathered. Combine & implement principles from information exchange (chapter 5) and problem identification (chapter 6). 3. Determine outcome goals before selecting development strategy. This requires precise definition of the “target of change.” The method for defining the target of change is in chapter 7, behavior regulation 4. Maximize involvement and participation of targeted employees during program development. A theme throughout this book is that participation enhances the likelihood of successfully achieving goals. Here, you are making “ownership” possible. 5. Communicate! Effective change requires continual interaction. Katz & Kahn were very clear when the y emphasized the importance of the adaptive subsystem. This subsystem’s greatest value is the acquisition of intelligence, which facilitates organizational adaptation and change. This subsystem’s primary tool is information exchange (see chapter 5 for effectiveness principles). Principles for effective training. At some point, OD specialists will also be trainers. To assist you in that process, we have provided four effectiveness principles for you to use: • Principle 1: Training should be skill-oriented and actively involve participants. Employees go to training because they are told to – given an option, they would probably go to work instead of training. Therefore, training sessions should have a limited number of learning objectives, include heaving doses of student participation, and be fast paced. There should be a heavy emphasis on application. 12-11 • Principle 2: Training sessions should be multi-media presentations involving as many of the participants’ senses as possible. With today’s media technologies, there is simply no excuse for not having a sophisticate, professional presentation of information. Employees have come to expect message delivery in a “high tech, action-packed” manner. Furthermore, the greater the number of senses stimulated, the greater the likelihood of successfully transmitting your message to the audience. • Principle 3: Do all that is possible to prepare participants before training begins. “Time is money” is an old slogan you have heard before. A two-hour meeting with 15 employees can get very expensive when you consider ho w much they make an hour. So, if time is to be efficiently used, participants should come to the session prepared. It is common for the OD specialist to provide reading and audio-visual materials, along with preparation assignments, to participants prior to the actual session. Plus, it’s a good idea to brief the participants’ supervisors before hand and ask that they insure a supportive environment exists for implementing change and request they communicate this sentiment to the participant. • Principle 4: Short-, intermediate, and long-run objectives of training must be tied directly to long-run organizational planning and worker needs. There are many meritorious change programs. But, their value to an organization is a function of the extent to which they contribute to organizational goal attainment. The tie-in must be real and specifically stated. If not, the development effort isn’t worth doing. In addition, development programs should be scrutinized in terms of worker needs. Recall Trist and Bamforth’s study of coal mining and the introduction of new technology (Chapter 4). There new technology was inherently superior to what was being used, but it had such an adverse impact of the workers’ social system that productivity actually decreased. Failure to remember this lesson could doom change efforts. 12-12