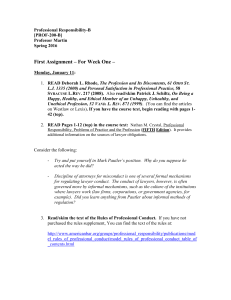

2006

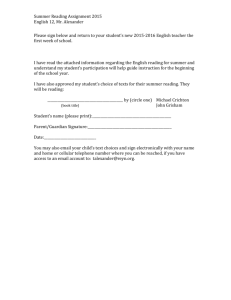

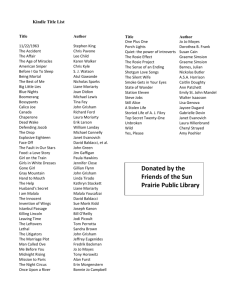

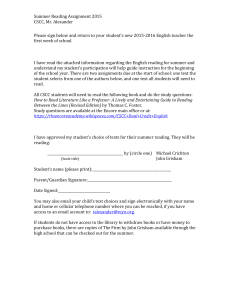

advertisement