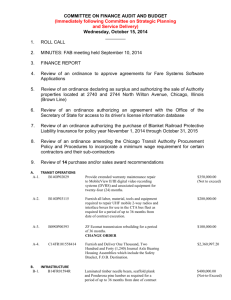

Horien v. City of Rockford - Robbins, Russell, Englert, Orseck

advertisement