- Bleecker Street Arts Club

advertisement

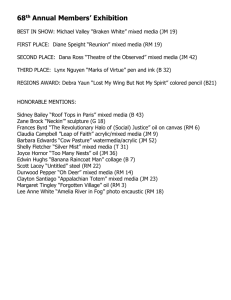

Service Industry: An Interview with Jay Batlle In “Life Lessons,” a short film directed by Martin Scorsese, Nick Nolte plays a tortured painter named Lionel Dobie, who experiences a creative block as a new exhibition of his paintings is about to open at a well-to-do gallery in Soho. Paulette, his assistant and live-in lover, is played by Patricia Arquette, who taunts Dobie with her irrepressible sexuality while denying him satisfaction. Paulette’s rejection of Dobie and his ensuing sexual frustration fuel a frantic but fruitful spurt of productivity, inspiring him to create large, emotionally charged paintings. At the end, Dobie’s exhibition is hailed as the work of a genius, and at the gallery opening he picks up another young, starstruck woman, promising her valuable life lessons. Scorsese gives us a portrait of the male artist, living the high life as a rich and famous painter in downtown Manhattan who can only paint when he experiences excruciating emotional pain. He is outwardly macho, but inwardly requires a perpetual state of turmoil in order to be creatively successful. I bring up the character of Lionel Dobie because he represents for me the myth of the artist to which the thousands of young art school students who descend yearly upon New York City aspire. It is precisely this fantasy (and the crushing reality that few artists actually become art stars) that is at the heart of Jay Batlle’s work. He works in sculpture, painting, and drawing, and these objects embody Batlle’s obsession with the idealized life of an artist as well as the temptations of “the good life.” Jay Batlle and I became fast friends at an opening at Nyehaus in Chelsea for an exhibition about San Francisco Bay Area art during the Beat years. It was an auspicious moment for me to meet Batlle for the first time, because he was in his element— hanging out amongst drawings and paintings from a pivotal moment in the West Coast art scene, accompanied by good drink, food, and animated conversation. It was then that I put two and two together and realized that I had seen his first exhibition at the Nyehaus gallery when it was still at the National Arts Club on Gramercy Square. It was called “Cutting out the Middleman,” alluding to the term in economics used to describe the removal of intermediaries in the supply chain: essentially Capitalism 101. Ironically, it was the last show for the gallery at that location, as Nyehaus is now amidst the many galleries of New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. Many of the works featured in this first exhibition were inspired by hotel stationery drawings by the late German artist, Martin Kippenberger. Kippenberger died at the age of 43 from liver cancer, and he documented his physical decline in a series of paintings based on Théodore Géricault’s, “The Raft of the Medusa” (1818-1819). In 2008, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art organized a retrospective of Kippenberger’s prolific career that came to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He was born in postwar Germany, where WWII was vivid in the memory and culture of the divided country. The generation of artists who preceded him was compelled to address the psychological results of the war, but Kippenberger led a revolution in his city of Cologne to repudiate the moralistic tones of his predecessors. His career could be likened to a tragic comedy, where irony and cynicism masked a deep and serious engagement with the history of art and its future possibilities, cut short by a life of excess. I find that same renegade yet slightly Machiavellian spirit in Jay Batlle’s work. A Californian at heart, Batlle is influenced by the legacy of West Coast artists like John Baldessari and Chris Burden, artists unafraid of embracing color, popular culture, and conceptually-driven art. Batlle is equally captivated by painting and sculptural movements from Europe like Arte Povera to CoBrA. His first studio was his childhood kitchen in Arizona where he lived with his father and learned to cook as a preteen by baking inedible cakes that allowed him to discern the difference between success and failure in all creative endeavors. Batlle’s whole oeuvre, in fact, exploits the dichotomy between the two extremes, with the understanding that sometimes you win, sometimes you lose, but that is the ultimate gamble of an artist living in New York. This interview takes place over a few weeks during the preparation of and following his exhibitions of paintings and drawings titled “Gourmand” at AFP Gallery in April and his drawings, sculpture, and cooking performance at Nyehaus in May 2012 titled “Parties of Six or More,” where Batlle showed drawings and a sculpture while he served 1500 roasted oysters and copious amounts of wine to the 250 visitors who came to his opening. KC: It seems that you are concerned with the question of “lifestyle,” but of an excessive nature: eating, drinking, and sex, while also living the life of an artist in New York with few monetary means. Sensual pleasure often emerges in your work, whether it is in your performances involving serving food, or in the erotic portraits of women you do on restaurant menu stationery (as though they were the plat du jour). What do you think about this? JB: Eating is something that I became obsessed with while living in NYC. The foodie culture here is probably the best in the world. You can get anything you want here, can’t you? The question of lifestyle came into the picture when I realized that this is why most artists move to New York, to realize this cinematic dream of the big loft, the beautiful muse, and eating out everyday at Mr. Chow’s. This fantasy is probably the driving force behind SoHo’s real estate success of the last 40 years, the soft cultural power of the American dream, in the form of the successful artist. I like to play with this in my practice, and so I use the stereotype of the male painter, with my wife, my beautiful muse, and greyhound, Seymour. My work has always been a critique of value, or why we choose to like something. KC: Can you go into detail about why Martin Kippenberger is such a huge inspiration for your work? JB: My show at Nyehaus in 2009 was mainly a sculpture show, where I was trying to set the record straight in New York. The show was about being in debt to all the people who help you along the way in your journey as an artist, so I made a giant collage on two canvases called “Free Lunch.” The collage was of my paper trail in the artworld glued on gigantic restaurant stationery I printed out on canvas. Nyehaus showed my book works in vitrines as well, which are blank Kippenberger hotel stationery books that I have filled with my own drawings. Formally the books are like Rauschenberg’s erased De Kooning piece, but in reverse: I was filling a void. We also featured original drawings by Kippenberger in that show to create a parallel, but my work is much more American and Southern Californian in intent and structure. It’s closer to Pop, while I see Kippenberger as a contemporary Dadaist. “Cutting Out The Middleman” was like a giant résumé to show how much I had done at that point, though I was still relatively under the radar of the New York art world. Honestly, I don’t know how important Kippenberger is for my practice, other than some formal generalizations and that I like the vulnerability in his work. It’s easy to say “Kippy” made stationery drawings and a big part of my practice is my restaurant stationery works, but a lot of artists have drawn on stationery, like Robert Gober, Elizabeth Peyton, Dieter Roth, and Sigmar Polke. I blow up restaurant stationery, and then doodle on them. Kippenberger’s sculptures had a bigger effect on me. Ultimately, my stationery practice came out of working and running restaurants in New York and Paris. When I was in college at UCLA, I saw Kippenberger’s “Peter” sculptures in a book, and that marked an important moment for my thinking about art. After UCLA I moved to Amsterdam on a fellowship and hung out with Georg Herold, an artist who was part of Kippenberger’s clique in Cologne and one of his best friends. I was ultimately expelled from the program in Holland for not working hard enough in my studio. I moved to New York and worked in a sandwich shop making $4.25 an hour, living in five story Chelsea walk-up with an aspiring English actress. At that time I made black and white ink drawings and sculpture that was very ephemeral. These sculptures subverted an object’s form and function because I made them out of wood that was literally falling apart. They were more like three-dimensional sketches and people thought the works were unfinished models, but instead it was a drawing approach to sculpture that you see everywhere in galleries these days. My first solo show in New York was at that tiny Chelsea apartment. I called it Flat Experiment #1. I showed a 9’ wood structure hanging from the ceiling–a ramshackle fire escape in form and very Arte Povera in spirit. I served spaghetti and meatballs and we drank martinis on the roof. The work was purchased for a private collection and the piece “lived” in Boston for nine years until a water leak caused the ceiling to cave in and destroyed the sculpture. It was a relief to think even art dies. KC: Let’s talk about the way that your art and the serving of food to your guests/viewers go hand in hand. JB: I’m interested in the interchangeability of wealth and power, and the blurring of boundaries between the two when it relates to indulgence and excess. Imagine you are waiting tables at a private party. At the beginning of the event, there is a host, the guests and then those who serve. The boundary between these two camps is clear at the start of the evening, but the interesting part is when the roles of server and served gets blurred towards the wee hours. I’m interested in when the host, the person paying the waiter, becomes equal to the hired person. This enables a sort of pure pleasure and perhaps straight out debauchery can ensue. There is a loss of clear roles, and the naming of these roles become abstract or lost. There is a shift in power position and an escape from class structure, and possibly capitalism. This was my intent in the oyster performance at Nyehaus, called “Please Help Yourself.” At a certain point I stopped serving even though there was plenty of food to go around, but most people didn’t go help themselves, they demanded service. So my friends who attended started shucking for themselves and others became servers, though I was “the artist.” KC: In the garden of Nyehaus, you installed a sculpture called “No Beginner’s Luck,” composed of Monopoly pieces stacked on top of each other. Tell me how this sculpture came about. JB: In 2007 I was asked to make a sculpture for a bank in London. I was traveling there and staying at the Arts Club in Chelsea, living out my English boarding school fantasies. I was going to make it with the production company Carlson & Co. in California, famous for producing Jeff Koons’ and Charles Ray’s sculptures. In my mind, I saw the finished work as this perfectly produced object–a 10′ cast aluminum totemic sculpture inspired by the classic game of capitalism, Monopoly. A team of fabricators would make it, and it would cost a lot to produce, but in my head the idea was too big to fail, I had to make it happen. So after two years of meetings and contracts and a little model; I got this huge commission from the bank, all on my own. The production of this trophy for traders would cost most of the commission, and I would make just enough to cover expenses and maybe get a new pair of John Lobb shoes. As the final negotiations came down and the contracts were signed, Lehman Brothers collapsed and the world economy went with it. I learned a big fucking lesson, which was to never quote projects in currencies where the production currency isn’t the same. The British pound was at 2.20 to the dollar, but dropped to 1.75 the day I was to get the wire from London to start the production of this piece which at this point only existed in my head. I had to renegotiate the price, because now the production cost more than the commission, and essentially I owed money on the contract out of my own pocket. There was an uncanny irony to the situation of making a piece critiquing the structure of capitalism and our childhood memories of “playing,” while the whole project came apart for financial reasons. I had to cancel the whole thing, which was a huge failure for me and a big lesson. Now, almost 5 years later, the finished work is at Nyehaus in “Parties of Six or More.” It’s a cast resin work with a beautiful metal pewter coating and finished with a white patina. It stands 10 feet high and is composed of the same forms initially commissioned by the bank, with one exception: I made the entire work from scratch, with my own hands and labor. I titled it “No Beginner’s Luck,” which seems to say it all. KC: Gordon Matta-Clark, an artist active in Soho in the 1970’s, is known for sculptures he made by carving abandoned buildings with chainsaws. He created “Food,” a restaurant on the corner of Prince and Wooster streets where artists would convene, share meals and cook for one another. It was a very idealistic moment. In the crumbling shells of buildings left derelict by the flight of industry from New York City in the 1970′s, artists sought more immaterial ways of expressing themselves that centered on community rather than selfreliance, on experiences rather than objects. Of course, many of them made both experiential as well as object-based art. How would you compare what transpired then to what is happening now, given the huge changes in the art world in the last forty years? How is what you are doing different from MattaClark, given your own historical context? JB: In my opinion, too much is happening too fast for anyone to notice what is valid or lasting right now, and forty years ago so little was happening and very few people were paying attention. People can go back historically and cherry pick. The more people involve themselves with art, the less effect it has. Art gets homogenized into the machine of the mundane. I am very calculated, but also extremely critical of what I do as an artist. I am trying to stand out, to break out, to make people stop and think and live. I still have to isolate myself in my mode of production, to remain edgy, but not elitist. The simple answer is that I’m not Matta-Clark and it’s not 1970, but more specifically, he was more of a hippie on tequila and I’m more of a bon vivant on burgundy. I don’t have clear intentions. I only believe I do. Don’t get me wrong, Matta-Clark and my work have a strong bond and a relationship historically. I just don’t want to close down the reading of my work too fast. Matta-Clark is a very big influence, specifically his sculpture, and the sculptural problem of props versus discrete objects or performance leftovers. My work has a very literal aspect to it, and I think Matta-Clark’s food/ sculpture/performance has this directness that I need and want from art. I don’t want to have some esoteric practice, or some fake narrative to validate why I do this or that. I need it to mean something, so something is at stake. Even if it’s idealistic, or romantic, my work needs a pathos…an urgency, a problem. Jay Batlle No Beginner’s Luck 2012 Cast resin, steel, metal B coating, patina, and clear coating Dimensions: Overall: 101” x 36” x 28”; Sculpture: 73” x 36” x 38”; Pedestal 28” x 28” x 28” Private Collection, NY Jay Batlle “Cutting Out The Middleman” (Amstel Version) 2009 Materials: Mix materials working fountain Dimensions: variable Courtesy of the Artist and Nyehaus Jay Batlle Cutting Out The Middleman Installation Nyehaus Gramercy Park 2009 Jay Batlle Cutting Out The Middleman Installation Nyehaus Gramercy Park 2009 Jay Batlle Cutting Out The Middleman Installation Nyehaus Gramercy Park 2009 Jay Batlle “Untitled” The Stationery Series 2008-2012 Materials: Ink, pencil, and watercolor on restaurant stationery Dimensions: 8.5″ x 11″ unframed Private Collection, Russia Jay Batlle “Basque Artist” The Stationery Series 2008-2012 Materials: Ink, pencil, and watercolor on restaurant stationery Dimensions: 8.5″ x 11″ unframed Private Collection, NY Jay Batlle “Sometimes Soup Is So Good” The Stationery Series 2008-2012 Materials: Ink, pencil, and watercolor on restaurant stationery Dimensions: 8.5″ x 11″ unframed Private Collection, NY Jay Batlle “Lunch With Silvia” The Stationery Series 2008-2012 Materials: Ink, pencil, and watercolor on restaurant stationery Dimensions: 8.5″ x 11″ unframed Courtesy the artist Jay Batlle “Simon Asleep With His Money” The Stationery Series 2008-2012 Materials: Ink, pencil, and watercolor on restaurant stationery Dimensions: 8.5″ x 11″ unframed Private Collection, London Jay Batlle “He Made Me” The Stationery Series 2008-2012 Materials: Ink, pencil, and watercolor on restaurant stationery Dimensions: 8.5″ x 11″ unframed Private Collection, Germany Jay Batlle “Batlle Reserva Performance” Clages Gallery Cologne 2011