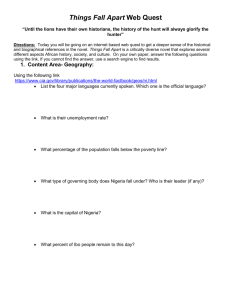

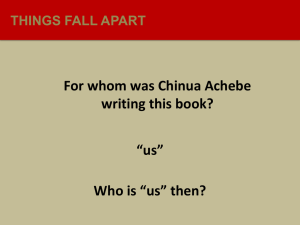

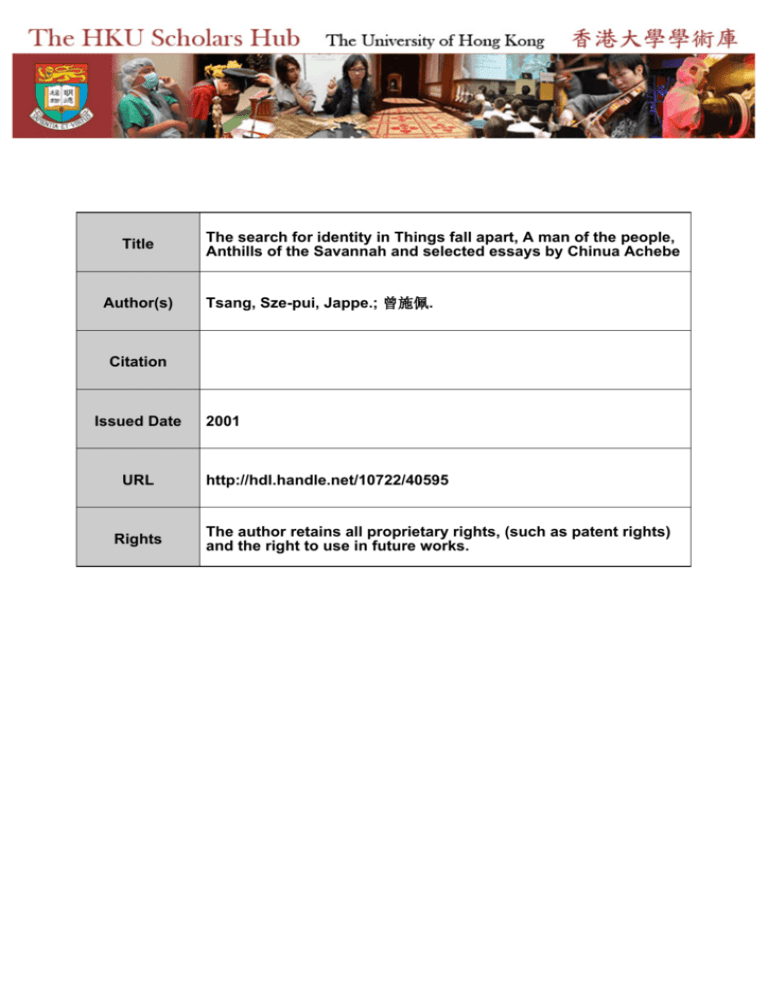

Title The search for identity in Things fall apart, A man of the people

advertisement