Coastal Marsh Management in the western Lake Erie Basin

advertisement

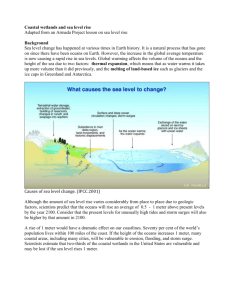

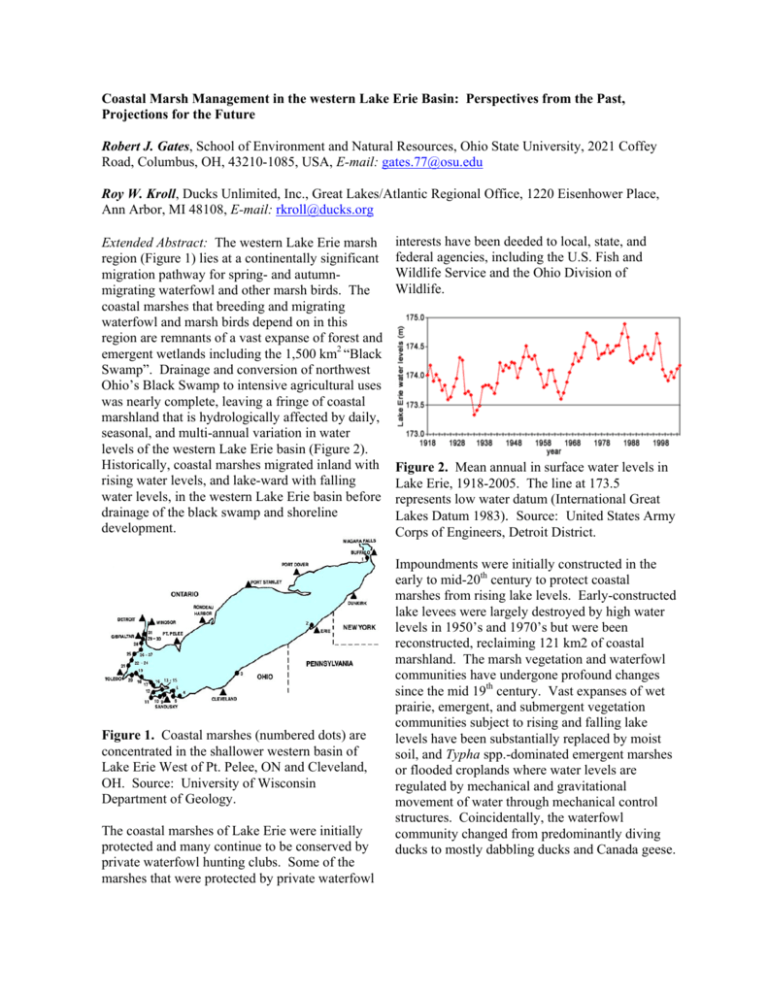

Coastal Marsh Management in the western Lake Erie Basin: Perspectives from the Past, Projections for the Future Robert J. Gates, School of Environment and Natural Resources, Ohio State University, 2021 Coffey Road, Columbus, OH, 43210-1085, USA, E-mail: gates.77@osu.edu Roy W. Kroll, Ducks Unlimited, Inc., Great Lakes/Atlantic Regional Office, 1220 Eisenhower Place, Ann Arbor, MI 48108, E-mail: rkroll@ducks.org Extended Abstract: The western Lake Erie marsh region (Figure 1) lies at a continentally significant migration pathway for spring- and autumnmigrating waterfowl and other marsh birds. The coastal marshes that breeding and migrating waterfowl and marsh birds depend on in this region are remnants of a vast expanse of forest and emergent wetlands including the 1,500 km2 “Black Swamp”. Drainage and conversion of northwest Ohio’s Black Swamp to intensive agricultural uses was nearly complete, leaving a fringe of coastal marshland that is hydrologically affected by daily, seasonal, and multi-annual variation in water levels of the western Lake Erie basin (Figure 2). Historically, coastal marshes migrated inland with rising water levels, and lake-ward with falling water levels, in the western Lake Erie basin before drainage of the black swamp and shoreline development. Figure 1. Coastal marshes (numbered dots) are concentrated in the shallower western basin of Lake Erie West of Pt. Pelee, ON and Cleveland, OH. Source: University of Wisconsin Department of Geology. The coastal marshes of Lake Erie were initially protected and many continue to be conserved by private waterfowl hunting clubs. Some of the marshes that were protected by private waterfowl interests have been deeded to local, state, and federal agencies, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Ohio Division of Wildlife. Figure 2. Mean annual in surface water levels in Lake Erie, 1918-2005. The line at 173.5 represents low water datum (International Great Lakes Datum 1983). Source: United States Army Corps of Engineers, Detroit District. Impoundments were initially constructed in the early to mid-20th century to protect coastal marshes from rising lake levels. Early-constructed lake levees were largely destroyed by high water levels in 1950’s and 1970’s but were been reconstructed, reclaiming 121 km2 of coastal marshland. The marsh vegetation and waterfowl communities have undergone profound changes since the mid 19th century. Vast expanses of wet prairie, emergent, and submergent vegetation communities subject to rising and falling lake levels have been substantially replaced by moist soil, and Typha spp.-dominated emergent marshes or flooded croplands where water levels are regulated by mechanical and gravitational movement of water through mechanical control structures. Coincidentally, the waterfowl community changed from predominantly diving ducks to mostly dabbling ducks and Canada geese. Currently, >90% of the remaining coastal marshes in the Lake Erie basin are impounded to protect the marshes from fluctuating lake levels because these marshes are “back-stopped” on the landward side by agricultural and urban development pressures which continue to the present. Water levels of the impounded marshes are typically managed to promote growth of natural wetland vegetation and flooded cropland that attracts autumn-migrating waterfowl, provides habitat for wetland dependent resident wildlife, and supply recreational opportunity for hunters and wildlifewatchers. Water-level management to promote growth of wetland vegetation within impounded marshes has introduced a hydro-period that did not correspond with historic hydrological conditions before regulation of Great Lakes water levels and impoundment of marshes and agricultural and coastal urban development. Nevertheless, contemporary marsh management has successfully conserved natural vegetation communities that support migrating waterfowl and other wildlife. Although impoundments were demonstrated to protect coastal mashes from rising lake levels in the western Lake Erie basin, they have been criticized as impairing the biodiversity, water quality, and hydrologic values of these wetlands. Yet there is evidence that impounded marshes do perform these ecological functions and values. The appearance and spread of invasive species, especially common reed (Phragmites australis), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), narrow-leaf cattail (Typha angustifolia), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea) and flowering rush (Butomus umbellatus) have created challenges for management of coastal marshes in the western basin. Marsh managers now manage marshes with longer hydroperiods that promote growth of persistent emergent and submergent plants, compared to managing with short hydroperiods that favor moist soil annuals. Management of flooded cropland continues mostly because it appeals to duck hunters, and limits spread of invasive wetland plant species. Regardless, flooded cropland provides little benefit to springmigrating waterfowl and detracts from the biodiversity, water quality, and hydrological functions and values of coastal marshes. Despite a general shift from managing flooded cropland and moist soil vegetation, autumn food resource availability is high in Lake Erie coastal marshes and sufficiently high in spring to meet the energetic needs of spring migrating waterfowl. Waterfowl hunting success remains high subject more to hunting pressure, annual variation in weather conditions and migration chronology than to food resources availability. Climate change, continued appearance and spread of invasive species, coastal development pressure, biodiversity concerns, multiple use demands will clearly affect management of the coastal marshes of Lake Erie in the future. Changing management paradigms (e.g. managing for spring vs. autumn resources), economic forces, and demographic changes in stakeholders and values will present profound challenges that marsh managers must adapt to. We present an historical perspective (Figure 3) on changes in management of coastal marshes to provide some insight into how the system will respond to ecological changes that are coming to the region, and to the societal pressures that also determine trajectories and endpoints of change Lake Erie’s coastal marshes. Although we focus on the Lake Erie marshes, because they comprise the largest contiguous area of marshland in the Great Lakes, our historical perspective and speculation on the future apply broadly to coastal marshes throughout the Great Lakes region. Figure 3. Pre-impoundment reconstruction of general vegetation distribution on the Winous Point Shooting Club. Source Gottgens et al. 1998, Wetlands Ecol. and Manage. 6:5-17.