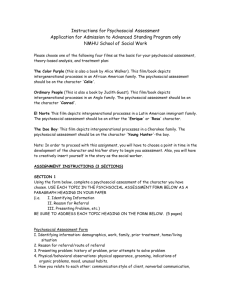

Psychosocial Work Conditions and Aspects of Health

advertisement