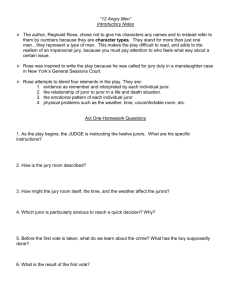

the rashomon effect, jury instructions

advertisement