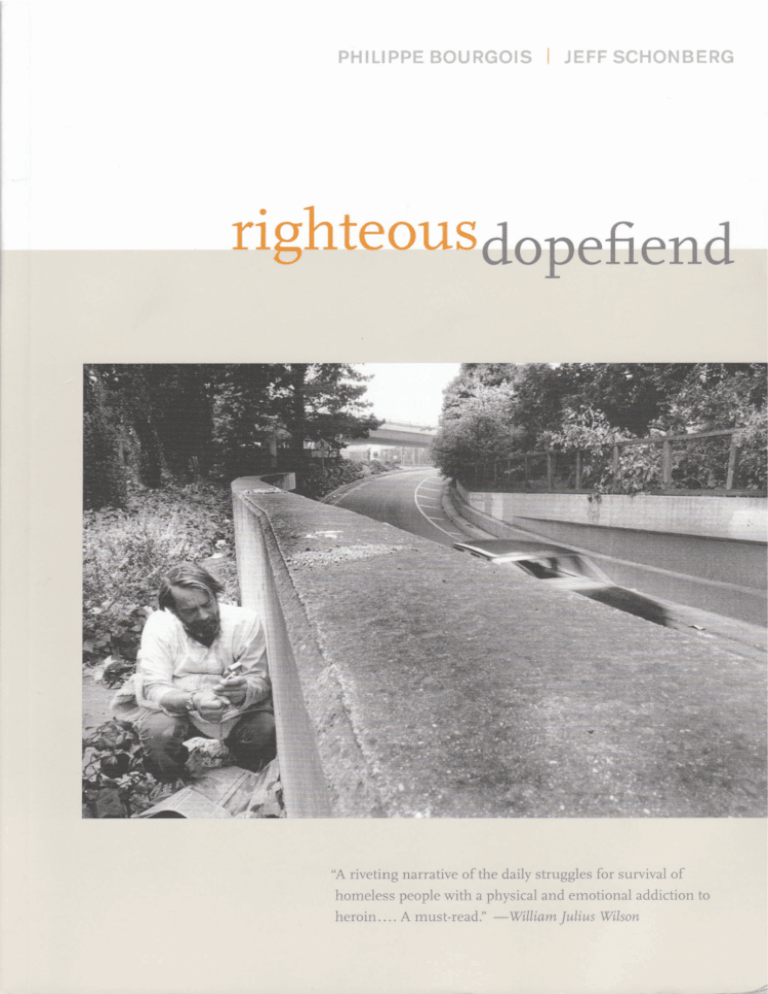

righteousdopefiend

advertisement