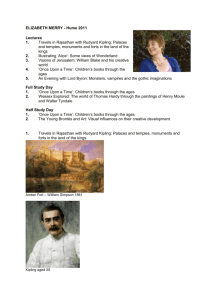

Something of Himself: Textual and Historical Revision in

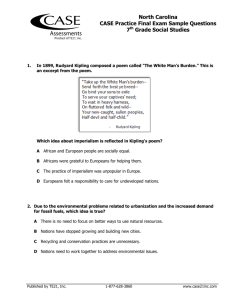

advertisement