Entire contents in - Progressive Librarians Guild

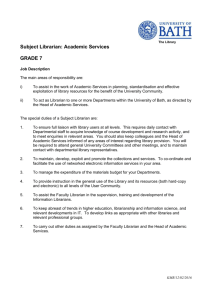

advertisement