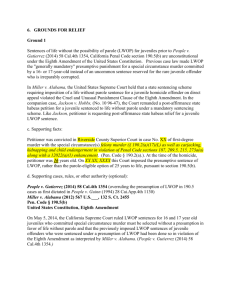

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

advertisement