Contingency-based Design of Management Control Systems

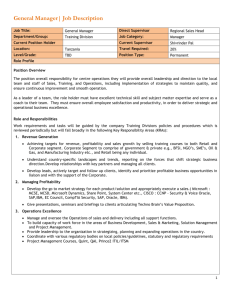

advertisement