economic profile of the agro-processing industry in south africa

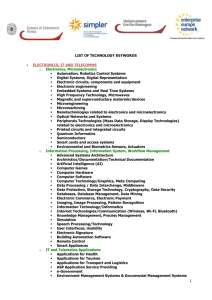

advertisement