Turkey - TENLAW

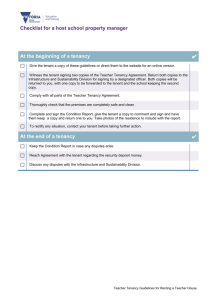

advertisement