Chap 7, lesson 2 Text - Springboro Community Schools

advertisement

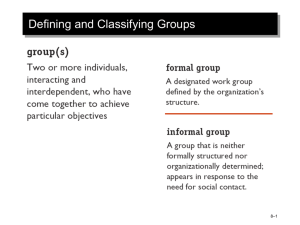

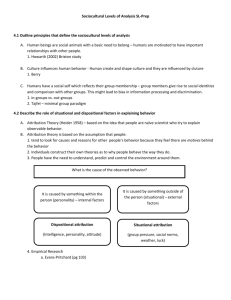

LESSON 2 Managers and Group Behavior Perception Quick Write Think of an experience in which someone got you to change your usual behavior. How did they accomplish it? B Learn About . . . • perception • how people learn • foundations of group behavior Have you ever experienced something with another person, and afterward realized that the two of you understood the experience completely differently? Maybe it’s happened at the movies, when you figured out who the villain was, and your friend had no idea—even though you were sitting together in the same movie! Or imagine in the business world that a certain manager’s assistant takes several days to make an important decision. Does she take so long because she’s slow, disorganized, and reluctant to make up her mind? Or is she thorough, thoughtful, and deliberate? Two different managers may have two different ideas about her. These two different interpretations are examples of different perceptions. Perception is the way people make sense of their world. Or, to put it a little more formally, perception is the process of organizing and interpreting sensory impressions to give meaning to the environment. What Influences Perception Consider another example of different perceptions. Bill shows up for a job interview at a large petroleum products firm—and he has a nose ring. Cathy, who is 45, is a marketing supervisor for the company. She’s likely to be Bill’s supervisor if he’s hired. But he may not get the job, because she’s not impressed with the nose ring. She checks in afterward with Sean. He is 22 and is the human resources recruiter who first brought Bill in to talk about a job. Sean gets an earful from Cathy: “That guy had a nose ring! What made you’d think he’d fit in around here?” Sean is puzzled. He can’t remember whether he even saw the nose ring when he first met Bill. He certainly didn’t think it was anything he needed to warn Cathy about. 200 CHAPTER 7 | Foundations of Individual and Group Behavior As you see, people’s perceptions are affected by their own attitudes, background, and life experience. Your assessment of another is also affected by where and how you both meet. And a person’s characteristics can also influence your interpretation of him or her. Someone who’s large and loud will stand out, and you will see that person differently than you will a quiet, unassuming individual at the edge of a crowd. Think how your impressions of people are shaped by the context in which you meet. Someone you meet for the first time in the school library working on a report may always seem studious to you, for instance. Someone you first meet at a party where everyone is all dressed up may seem rather glamorous and exciting. Someone you meet on a Saturday afternoon when everyone in the group is just goofing off at the neighborhood pizza place may seem hard to take seriously later on. And if someone you trust and admire introduces another person to you, that introduction will make you think well of the new person. “If she’s a friend of Bill’s, she must be OK,” you are likely to think. Vocabulary B • perception • attribution theory • fundamental attribution error • self-serving bias • learning • operant conditioning • social learning theory • shaping behavior • group • role • norms • status • social loafing • group cohesiveness How Managers Judge Employees Much research into perception has focused on studies of how people see inanimate objects. The pictures in Figure 2.1 are good examples of how your eyes can play tricks on you. But managers have to be most concerned with how people perceive other people. When people look at other human beings, they draw conclusions and make assumptions about them. They try to explain other people’s behavior—often based on incomplete information. Suppose you see a young woman wearing a jacket with the logo of a particular baseball team. Does the jacket mean she’s a fan? Or does it just mean that she was chilly, and her boyfriend gave her his jacket to keep her warm? Attribution Theory Your perceptions and judgments about a person, then, are based on assumptions you make about them. Many of the assumptions have led researchers to develop attribution theory. Attribution theory is based on the premise that people judge other people differently depending on the meaning they attribute to a given behavior. When you look at another’s behavior, you try to decide whether the behavior is internally or externally caused. Internal causation has to do with intents and motives that the What do you think of this man? If you were interviewing him for a job in your company, what would be your first reaction? Positive? Think again. This is a photo of Ted Bundy, one of America’s most notorious serial killers. Corbis/Bettmann LESSON 2 | Managers and Group Behavior 201 Old woman or young wom an? Two faces or an urn? A knight on a horse? F I G U R E 2.1 Perceptual Challenges: What Do You See? person can control. It’s the things someone does “on purpose.” Externally caused behavior gets into things beyond the individual’s control. If an employee is late to work on the new boss’s first day, the new boss may think that employee just has a bad habit of often being late. But in fact, the tardiness may be externally caused—there may be a transit strike, for instance, or perhaps the employee had to take his car to the shop after being rear-ended in traffic. A manager trying to decide whether another person’s behavior has internal or external causes usually looks at three factors: 1. distinctiveness 2. consensus 3. consistency. The first factor, distinctiveness here refers to whether the behavior shows up everywhere in someone’s life, or just under certain circumstances. Take an employee’s tardiness, for example. A manager may judge in one way an employee who is always running late. But the same manager may judge in another way another employee who is late just once, and for a specific reason such as unexpected construction on the road. Consensus, the second factor, refers to problems that everyone has. If all the employees who took that route in to the office got tangled up with the same construction project, their managers will judge their lateness less harshly. If one employee is the only person who has a problem, the manager’s judgment against him or her will be harsher. The manager will think the problem behavior has an internal cause. Consistency is the third factor. If a person is late every morning, the boss is likely to think the behavior has an internal cause—something the employee should be able to get a grip on. Figure 2.2 illustrates how managers look at individual behavior in light of the three factors in attribution theory. 202 CHAPTER 7 | Foundations of Individual and Group Behavior Observation Attribution of Cause Interpretation High External Distinctiveness Low Internal Individual behavior High External Consensus Low Internal High Internal Consistency Low External F I G U R E 2.2 The Process of Attribution Theory How Attributions Can Be Distorted Researchers have learned from their study of attribution theory that errors or biases distort attributions, or people’s judgment of others’ behavior. The researchers have found that when most people judge others, they tend to assume more behavior has internal causes than is the case. The boss worried about the late employee may see an internal cause of laziness but be unaware of the employee’s problems with irregular bus service. There’s a special term for these distortions: fundamental attribution error, the tendency to underestimate the influence of external factors and overestimate the influence of internal or personal factors when making judgments about others’ behavior. This works in reverse, too. Individuals tend to regard their own success as the result of their hard work and other internal factors, but tend to ascribe others’ success to external factors, such as luck. Researchers use the term self-serving bias to refer to the tendency for individuals to attribute their own success to internal factors while blaming external factors for their failures. Shortcuts Managers Use in Judging Others As you may have gathered, managers must keep an eye on many different things and people in the workplace. All this observing and interpreting takes time and effort, so managers often turn to shortcuts to help them. These often do save time and help them make accurate assessments quickly. The shortcuts aren’t foolproof, though. A manager who tries to “speed read” his or her staff runs the risk of misreading someone completely (see Figure 2.3). LESSON 2 | Managers and Group Behavior 203 Here are some of these shortcuts: • Selectivity, meaning that a manager decides to look at only certain indicators before judging someone. (“If he went to my old school, he’s probably pretty good.”) • Assumed similarity, or the “like me” effect, in which the observer sees himself or herself in the person he’s observing. A manager may want challenge and responsibility in her work—and may assume, incorrectly, that everyone else does, too. This misperception is likely to get in the way of good communication in the workplace. • Stereotyping is another shortcut. A manager may believe “All older workers are just waiting to retire,” or “The younger generation can’t be trusted to handle customer service calls.” • The halo effect is another shortcut—a tendency to let one fact about someone govern one’s entire picture of that person. For a young person who was bored last year with a tired-sounding English teacher, the enthusiasm of a young new teacher may be very appealing. But a good teacher needs to bring more to the classroom than just enthusiasm, and the halo effect may keep students from noticing the new teacher’s shortcomings. • In the self-fulfilling prophecy, an employee ends up acting out the manager’s prediction for him or her. It starts when the manager develops a perception of an employee, including a prediction of how well (or not) that employee will do. A manager who believes he is in charge of a group of overachievers will be pleased at how well they do. But if the manager thinks she’s supervising a group of people who can’t quite cut it, she will find that this group, too, will act out the script that’s been written for them. (Something similar often goes on in schools between teachers and students.) SHORTCUT Selectivity Assumed similarity Stereotyping Halo effect Self-fulfilling prophecy WHAT IT IS DISTORTION People assimilate certain bits and pieces of what they observe dep ending on their interests, background, exp erience, and attitudes People assume that others are like them People judge others on the basis of their perception of a group to whi ch the others belong People form an impression of others on the basis of a single trait People perceive others in a certain way, and, in turn, those others behave in ways that are consistent with the perception F I G U R E 2.3 Distortions in Shortcut Methods in Judging Others 204 CHAPTER 7 | Foundations of Individual and Group Behavior “Speed reading” others may result in an inaccurate picture of them May fail to take into accoun t individual differences, resulting in inco rrect similarities May result in distorted judg ments because many stereotypes have no factual foundation Fails to take into account the total picture of what an individual has done May result in getting the behavior expected, not the true beh avior of individuals How Understanding Perceptions Helps Managers Be More Effective In any event, managers must recognize that their employees respond to perceptions, not necessarily to reality. An employee’s performance review may be a model of objectivity and fairness. But if the employee thinks it’s unfair, that’s the perception he or she will act on. The company may end up losing an employee it would prefer to keep. Managers need to pay close attention to how employees perceive both their jobs and the company’s management practices. How People Learn To explain and predict behavior, a manager also must understand how people learn. Almost all complex behavior is learned. Learning is any relatively permanent change in behavior that occurs because of experience. In this sense, learning goes well beyond things you study in school. You are learning from your experiences all the time. How do people learn, though? Psychologists have two popular theories to explain the way people pick up new patterns of behavior: operant conditioning and social learning theory. Operant Conditioning Operant conditioning is a behavioral theory that argues that voluntary, or learned, behavior is a function of its consequences. People learn to behave so that they get what they want and avoid what they don’t want. This principle covers all kinds of situations. It covers students studying to get good grades on exams. And it applies to suburban office workers figuring out how early to leave for work to avoid rush-hour traffic. The late Harvard psychologist B.F. Skinner is linked with this theory. He didn’t invent it, but built on a foundation of earlier work in the field. He has his critics, but even the staunchest among them admit that his principles work. Skinner argued that creating pleasing consequences for a particular behavior would result in more of that behavior. Behavior that is not rewarded, or is even punished, is less likely to be repeated. Once you understand this principle, you’ll see it in action everywhere. You’ll also understand that some of the reinforcements—the positive or negative consequences intended to affect behavior—are implied, rather than openly stated. A real estate agent, for instance, finds that having a high income depends on generating many listings and sales in his or her territory. Probably no one had to tell the agent that, though. The agent just figured it out and started hustling. Sometimes even when linkages are made explicit, they encourage behavior that’s not otherwise a good idea. A supervisor facing a crunch on a big project may encourage employees to put in lots of overtime during the weeks of the project, and may tell them they’ll be rewarded accordingly during their next performance appraisal. But if LESSON 2 | Managers and Group Behavior 205 the appraisal arrives and includes no rewards for the overtime during the big project, the employees may decide not to push so hard the next time a project comes up. Social Learning Theory Social learning theory is another concept about how people learn. Social learning theory is the theory that people can learn through observation and direct experience. You observe what happens to other people, and you hear about their experiences, in addition to paying attention to your own. Among the models you learn from is the behavior of parents, teachers, brothers and sisters, friends, and other adults such as relatives and neighbors—and even movie and TV stars. Social learning theory is an extension of operant conditioning. It assumes that consequences shape behavior. But this theory also acknowledges that people learn by watching others. It acknowledges, too, the importance of perception in learning. People respond to the way they perceive and define consequences. They don’t necessarily respond to the consequences themselves. Central to social learning theory is the notion that different models influence an individual differently. The kind of influence a model has on you reflects four specific processes: 1. Attentional processes: To learn from a model, you have to recognize and pay attention to that model’s critical features. The models that influence you most are repeatedly available ones you consider attractive, important, or similar to you. 2. Retention processes: A model’s influence will depend on how well you remember the model’s action, even when the model is no longer available. 3. Motor reproduction processes: After you have observed a model in action, you still have to perform the actual physical activities. 4. Reinforcement processes: You will be motivated to follow the model’s cues if you get positive incentives or rewards for doing so. Reinforced behaviors will get more attention. Besides, you will learn them better and perform them more often than you will behaviors that don’t get attention. How Managers Shape Behavior Managers must focus on how to teach employees to behave in ways that benefit the organization. A manager will often attempt to mold employees by guiding their learning in graduated steps. Shaping behavior is the term for systematically reinforcing each successive step that moves someone closer to a desired behavior. If employees are already “with the program,” managers may not have to teach them much. But if the workers are far from the goal, their managers may have to get them there by “baby steps,” with reinforcement all along the way. Suppose a company is trying to get an employee who is always half an hour late to arrive at work on time. If the employee manages to come in only 20 minutes late, that’s an improvement— which the boss should reinforce with praise. 206 CHAPTER 7 | Foundations of Individual and Group Behavior There are four ways to shape behavior: 1. positive reinforcement 2. negative reinforcement 3. punishment 4. extinction. Positive reinforcement you have already met: The boss who praises the tardy employee for being “only” 20 minutes late is giving positive reinforcement. Negative reinforcement involves issuing rebukes or criticisms in response to bad behavior. If a group of employees keeps taking too long for their morning coffee break, the boss can decide to complain to them directly every day until the problem stops. That would be negative reinforcement. Punishment is probably a familiar concept to you. An employee who shows up for work drunk, for instance, might be suspended without pay for a couple of days and sent home. Extinction is the fourth tool. You can use it in situations like this: An employee keeps raising his hand to speak at the weekly staff meetings and then asks irrelevant questions. This wastes everyone’s time—but it may not be worth it to the manager to use negative reinforcement. Instead, the manager may simply stop calling on the employee during the weekly meetings. This saves time right away, and eventually the employee will stop trying to ask the irrelevant questions. How Understanding Learning Helps Managers Be More Effective Managers can benefit from understanding the learning process, including the four ways to change behavior and the four processes that determine how people learn from their models. Managers should also think about how actively they will manage their employees’ learning, through the rewards they allocate and the examples they set. If managers want a certain type of behavior, but reward another type, they shouldn’t be surprised if they get what they reward, rather than what they want. Foundations of Group Behavior In the last lesson, you read about the sources of individual behavior. The behavior of individuals in groups, however, is not the same as the sum total of all their individual behavior. People act differently in groups. To understand organizational behavior better, you have to study groups. Groups A group is two or more interacting and interdependent individuals who come together to achieve particular objectives. Groups can be formal or informal. A group set up by a company’s managers to prepare the staff for an office move is a good example of a LESSON 2 | Managers and Group Behavior 207 formal group. The five or six people who meet in the lobby every morning at 10:30 to go out for coffee are an example of an informal group. So is the group of four or five friends you get together with regularly on Saturday nights. Why do people join groups? For many different reasons. And people belong to a number of different groups, each of which provides different benefits to their members. Figure 2.4 details some important reasons for joining groups. The Basic Concepts of Group Behavior The foundation for understanding group behavior consists of roles, norms and conformity, status systems, and group cohesiveness. Roles A role is a set of expected behavior patterns attributed to someone who occupies a given position in a social unit. Even in a group as informal as your Saturday night pals, there are probably a number of roles. If you think about it, for instance, you may realize that one of your friends usually takes the initiative to suggest which movies to see. In an organization, employees try to figure out their roles and learn what they are supposed to do. They take their cues from the boss and their coworkers, and maybe even from their job descriptions. And they may find themselves in conflict from different roles. A newly hired professor, for instance, may face pressure from colleagues to grade strictly to hold up standards—and from students to grade generously and keep everyone’s average in good shape. REASON Security Status Self-esteem Affiliation Power Goal achievement PERCEIVED BENEFIT Gaining strength in number s; reducing the insecurity of standing alone Achieving some level of pre stige from belonging to a particular group Enhancing one’s feeling of self-worth—especially me mbership in a highly valued group Satisfying one’s social nee ds through social interaction Achieving something throug h a group action not possib le individually; protecting gro up members from unreas onable demands of others Providing an opportunity to accomplish a particular task when it takes more than one person’s talents, kno wledge, or power to complete the job F I G U R E 2.4 Reasons People Join Groups 208 CHAPTER 7 | Foundations of Individual and Group Behavior Why do people join the Rotary Club, a service organization, in their community? Research says that they do so in search of security, status, self-esteem, affiliation, power, or goal achievement. Eric S. Lesser/Getty Images, Inc. How Norms and Conformity Affect Group Behavior All groups have norms—acceptable standards shared by the members of a group. Norms govern the way people dress at most companies, for instance. Most places don’t have uniforms or written standards for attire. But they do have an informal standard, and you would know if you fell short or dressed too formally. Sometimes a new employee may continue to wear a suit until coworkers tease and pressure him into more-casual attire. The area of effort and performance is another part of work life generally governed by norms rather than explicit rules. A company may have an official start of 8 a.m.—but does the workday really start on the dot of eight? Do people cut out right at the official quitting time? Or do some stay later because they came in later? Norms around such questions can be powerful predictors of employee performance. Loyalty to an organization is another area where norms, rather than formal rules, govern. Few managers would tolerate employees who ridicule the organization, and employees at any rank who are unhappy and seeking new employment elsewhere know they should be discreet about their searches. On the other side of the coin, the desire to show loyalty often leads people to carry home briefcases full of work, come in on weekends, and even accept transfers to cities they wouldn’t otherwise choose to live in. Solomon Asch studied group norms and the way they push people toward conformity (see “A Management Classic,”). People want to belong to the group and to avoid being visibly different. And when an individual’s opinion of objective data differs significantly from that of others in the group, the person feels pressure to align his or her opinion to conform to those of the others. LESSON 2 | Managers and Group Behavior 209 Status, and Why It Matters Status is a prestige grading, position, or rank within a group. People have been thinking about status for about as long as human beings have been on the earth, it appears. Concerns about status can affect people’s behavior when they feel a difference between the way they see their status and the way others perceive it to be. Status may be informally conferred, based on education, age, skill, or experience. “Informal” here doesn’t mean “unimportant”—or “unclear,” either. Anything can be a source of status. And members of groups are pretty clear on who in the group has status and who doesn’t. Within organizations, it’s important that employees believe the organization’s formal status system aligns with its informal system. If the organization makes much of assigning prestige parking spaces to top officials, and one of the top spots is given to someone who wouldn’t have had a job at the company except that he was the general manager’s brother-in-law, that will cause a problem for the employees. And conversely, if a senior executive has a less desirable office than someone else farther down the organizational chart, that will send a message of confusion through the company. A Management Classic Solomon Asch and Group Conformity Can pressure to fit in with a group be strong enough to change a member’s attitude and behavior? According to some classic research by Solomon Asch (1907-1996), the answer is Yes. Asch’s study involved groups of seven or eight people in a classroom. An investigator asked each of them to compare two cards. One card had one line. The other card had three lines of varying length. As you see in Figure 2.5, one of the lines on the threeline card was identical to the line on the one-line card. The difference in line length was obvious. The test subject was to announce aloud which of the three lines matched the single line on the card. Under ordinary conditions, the error rate was under 1 percent. But what if all the members of the group began to give incorrect answers? Would the unsuspecting subject (USS) change his or her answer to match the others’? That was what Asch wanted to find out. He arranged the group so that the USS was unaware that the experiment was fixed. The chairs were set up so that the USS went last to announce his or her decision. The experiment began with two sets of matching exercises. All the subjects gave the right answer. On the third set, however, the subject gave an obviously wrong answer. For the cards in Figure 2.5, for instance, the subject would say “C” when the obvious answer was “B.” Then it was the turn of the USS. This person faced a decision: whether to publicly state a perception that differed from that of the others in the group. The USS had to 210 CHAPTER 7 | Foundations of Individual and Group Behavior consider, “Am I willing to disagree publicly? Or will I change my answer to fit in with the group?” Asch ran the experiment time and again, and he found that his subjects conformed about 35 percent of the time. That is, they gave an obviously wrong answer because they preferred to agree with the group than to be correct but out on their own. The Asch study has a lot to say to managers concerned with how groups behave. Individuals tend to go with the pack. That’s why managers should encourage a climate of openness so that employees can discuss problems without feeling that there are “right” or “wrong” answers—and they will be punished for giving the wrong answer. X A B C F I G U R E 2.5 Examples of Cards Used in the Asch Study How Group Size Affects Group Behavior The size of a group affects its behavior—but just how depends on different criteria. Small groups complete tasks faster than larger ones do. But for solving problems, larger groups are better, because of their potential for diversity and for reaching out to more sources to gather facts. This advantage kicks in with groups starting with a dozen members. A good size for a group set up to do something with the facts already in hand is from five to seven members. Researchers have studied a phenomenon known as social loafing—the tendency of an individual in a group to decrease his or her effort because responsibility and individual achievement cannot be measured. For example, a group of four tends to get more done than a group of three—but at an individual level, the group of four, per person, is less productive than the trio. Are Cohesive Groups More Effective? It makes sense that groups with a lot of internal disagreement and lack of cooperation should be less effective than are groups whose members generally agree, generally like each other, and generally cooperate with each other. Researchers use the term group cohesiveness—to refer to the degree to which members of a group are attracted to each other and share goals. The more the members of the group are attracted to one another and the more group goals align with individual goals, the greater their cohesiveness. But there’s a little more to this question of cohesiveness than that. What counts in making a group effective is not only cohesiveness, but also attitudes. A group may stick together very well, but if the members’ attitudes toward their goals aren’t positive, they won’t achieve them. You’ve no doubt seen this in school. There may be a group of students at the back of the classroom who regularly disrupt things, for instance. They’re a cohesive group, all right—they’re all good buddies who laugh at each other’s jokes. But they’re not “with the program,” and they aren’t helping anyone meet the teacher’s goals for the class. LESSON 2 | Managers and Group Behavior 211 Figure 2.6 shows the findings of scholarly research into the question of cohesiveness, goals, and productivity. A cohesive group aligned with organizational goals will be highly productive. A less cohesive group that still is aligned with organizational goals will be moderately productive. A cohesive group that’s not in alignment with organizational goals will be less productive than its members would be on their own—that’s where the group of classroom cut-ups fits in. And when a group is not particularly cohesive and or well aligned with organizational goals, being in a group has no particular effect on productivity. So it’s very important that managers know how to get groups to work together. The next chapter will discuss how to do that. Air Force special forces units are such close-knit groups that each member knows what the others are thinking and how they will react in certain circumstances. Courtesy of US Air Force Cohesiveness Alignment of Group and Organizational Goals High High Low Strong increase in productivity Decrease in productivity Low Moderate increase in productivity No significant effect on productivity F I G U R E 2.6 The Relationship Between Group Cohesiveness and Productivity 212 CHAPTER 7 | Foundations of Individual and Group Behavior CHECKPOINTS Lesson 2 Review Using complete sentences, answer the following questions on a sheet of paper. 1. What three things does a manager trying to decide whether another person’s behavior has internal or external causes usually look at? 2. What is fundamental attribution error? Give an example. 3. What five shortcuts do managers use to “speed read” their employees? 4. What four processes determine the influence a model has on someone’s behavior? 5. What is “shaping behavior”? Give an example. 6. What are four ways to shape other people’s behavior? 7. What are six reasons that move people to join groups? 8. In Solomon Asch’s experiment, what percentage of the time did people conform? Why did they conform? Applying Your Learning 9. Describe an experience in which you or someone close to you was assigned to a group to achieve some specific goals.Was the group cohesive? Did the group’s cohesiveness, or lack of it, help or hinder the achievement of its goals? LESSON 2 | Managers and Group Behavior 213