LAW 110:2 - Law Library - University of British Columbia

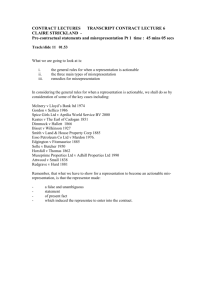

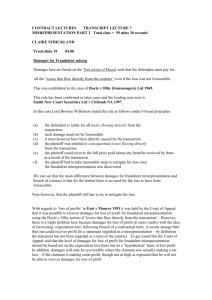

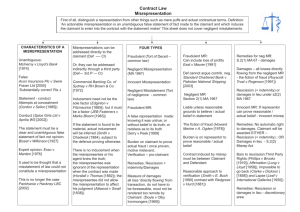

advertisement