Extract

advertisement

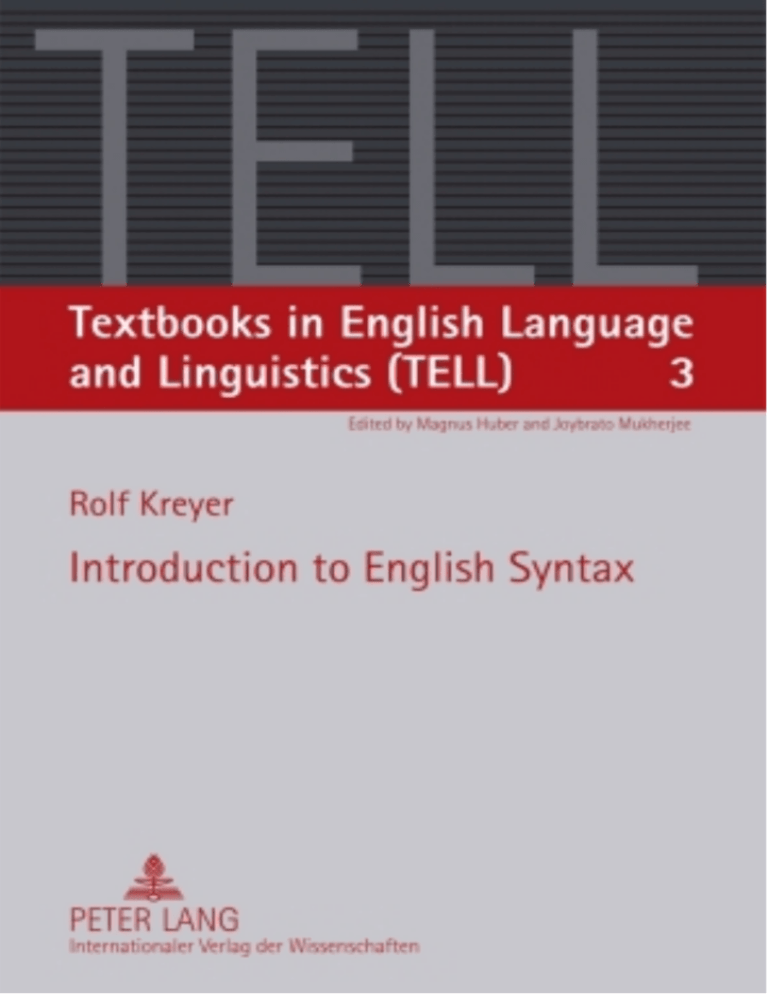

Kreyer, Rolf: Introduction to English Syntax (ISBN 978-3-631-55961-1) Introduction The present book provides an introduction to the description and analysis of English syntax. Syntax can be defined as follows: The term 'syntax' is from Ancient Greek sýntaxis, a verbal noun which literally means 'arrangement' or 'setting out together'. Traditionally, it refers to the branch of grammar dealing with the ways in which words, with or without appropriate inflections, are arranged to show connections of meaning within the sentence. (Matthews 1981: 1) The units of syntactic description occupy a central position among the units that linguistics is concerned with: in syntactic units, individual words are combined with each other to form larger units of communication, namely phrases (e.g. The President), clauses (e.g. The President ate a pretzel) and sentences (Because the President ate a pretzel he fainted). Sentences, on the other hand, are the building blocks of texts. This grants syntax a central position among the other disciplines of linguistics, as shown in Figure 0.1. Phonetics/ Phonology Morphology/ Lexicology Syntax sounds - morphemes - words - phrases - clauses - sentences Textlinguistics - texts Figure 0.1: The central position of syntax and syntactic units. The main concern of syntax lies in the structural description of the units in bold print in Figure 0.1. Syntax explores and describes the rules and principles according to which words are arranged in phrases, phrases are arranged in clauses, and words and phrases are arranged in sentences. One of such rules, for instance, is that in present-day English the subject, typically representing the doer of an action (or 'agent') should be expressed first (i.e. The President), the verb that refers to the action itself second (i.e. the verb form ate), and the object, typically referring to the entity that undergoes the action (or the 'patient') third (i.e. a pretzel): therefore, the sentence in (1) is in line with the rules of English syntax (i.e. it is grammatically well-formed), while the sentences in (2) and (3) are not (i.e. 2 Introduction they are grammatically ill-formed): examples (2) and (3) are thus marked with an asterisk (*), which indicates the lack of grammatical correctness. (1) The President ate a pretzel. (2) *The President a pretzel ate. (3) *Pretzel President the ate a. Note that it is of course possible to re-arrange the items so that other grammatically well-formed sentences with different orders of the words of example (1) are achieved. For example, the passive variant of (1) would have the patient of the action in front position, a form of the verb be and the past participle of the verb eat in second position and the agent of the action in final position (with the agent being no longer an obligatory element, but an optional 'by-agent' that can also be left out): (4) A pretzel was eaten by the President. Syntax is devoted to the description of the set of rules that produce all the grammatically well-formed sentences in a language – e.g. sentence (1) but not sentences (2) and (3) – as well as the analysis of the operations by means of which we can derive certain (and more complex) syntactic structures, e.g. sentence (4), from other (and more basic) structures, e.g. sentence (1). In addition, syntactic structures also make reference to aspects of meaning. Consider example (5). (5) ?A pretzel ate the President. This sentence is marked with a question mark because it is dubious. On the one hand, it is grammatically well-formed as it represents the same syntactic structure (subject – verb – object) as sentence (1) using the same verb. On the other hand, the sentence in (5) is not meaningful as the action that is described (i.e. eating) is not compatible with the agent of the action: inanimate entities like pretzels cannot eat anything. That is, although the sentence is grammatically well-formed, it is not meaningful – at least not in its literal sense and according to our shared world-knowledge. This makes clear that an introduction to syntax will also have to take a look at the units below the units of syntax, i.e. words. In addition to the aspect of 'meaningfulness' discussed above, words are relevant since they are the building blocks of syntactic units and influence their structure. Phrases, for instances, are classified with regard to the word class of the most important word in the phrase, e.g. the phrase The President is a noun phrase, because the central word (President) is a noun. On the other hand, syntax is partly concerned with texts, Introduction 3 since clauses and sentences are the building blocks of texts and, often, textual requirements influence the form a clause or a sentence takes. For instance, the choice between active and passive, as in (1) or (4), can be motivated by the structure or function of the text in which a sentence occurs. The relation of syntax to neighbouring disciplines and their units is shown in Figure 0.2. Phonetics/ Phonology Morphology/ Lexicology Syntax Textlinguistics sounds - morphemes - words ļ phrases - clauses - sentences ļ texts Figure 0.2: Syntax and its relation to elements of linguistic description. The influence of textual requirements already hints at the fact that syntax is not only about grammatical well-formedness but also about the acceptability of a sentence in a given situation, context or genre. Acceptability does not capture the correctness of a sentence but whether it is an appropriate, idiomatic and, thus, generally accepted utterance in a particular setting. Often, sentences are acceptable in certain contexts even though, strictly speaking, they are not grammatically well-formed or at least grammatically deviant. Consider sentences (6) to (8). (6) Gotta be joking. (7) They're enough funny, innit? (8) !A pretzel the President ate. The sentence in (6) is perfectly acceptable in informal spoken language, although it does not conform to written English syntax. This example illustrates that what one finds in English grammar books has traditionally been restricted to written and formal language. The sentence in (7) is not in line with standard English grammar rules either because, firstly, the tag question innit (as a variant of isn't it) is not the negative equivalent of the verb in the main clause (that is, the tag question should be, according to standard English grammar, aren't they) and because, secondly, the word enough is used to premodify the adjective funny, which is not possible in standard English grammar either. Both deviations from standard English are, however, perfectly acceptable in certain contexts, e.g. in the informal speech produced by teenagers in and around London. The sentence in (8) provides yet another example of the clash between grammatical well-formedness and acceptability: while this sentence is not in line with the ba- 4 Introduction sic word order of English (which requires the subject to be in first position and the object in postverbal position), this variant with a 'fronted' object is acceptable in certain (spoken) contexts, for example if the speaker wants to stress that the President ate an pretzel and not, say, a doughnut: "A pretzel the President ate, not a doughnut". The exclamation mark in front of example (8) shows that this structure is unusual and only acceptable in certain situations. What examples (6) to (8) illustrate is the need for a description of English syntax to also accommodate for sentences that may not be admissible in formal writing but that are acceptable in spoken language, given that speech is prioritised over writing in modern linguistics for various reasons (cf. Lyons 1981: 11-17): for example, every human being acquires speech before writing, and virtually all language users produce much more spoken language than written language. In addition to the situation- or genre-related acceptability of sentences, sentences can also be (non-)acceptable from a psychological or cognitive point of view. The sentence in (9), for example is grammatically well-formed and meaningful but sentences of this kind will usually not be found in authentic language data, since they are too difficult to understand. (9) The dog the cat the rat bit chased died. This example illustrates multiple reduced relative clauses. Note that reduced relative clauses are grammatical and that a single reduced relative clause is easy to understand. That is, the sentence The dog the cat chased died does not cause any difficulties. Problems arise when the noun cat is postmodified in a similar way together with a postmodification of dog, as example (9) shows. In that case, it is difficult to understand the sentence, i.e. that a particular dog died, namely that dog which chased this one cat that was bitten by the rat. Examples of the above kind hint at psychological processes relevant for the production and reception of syntactic units. These are explored in the field of psycholinguistics, which is also concerned with the psychological reality of the units of syntactic analysis. The aim and scope of the present book follows from the core ideas and key concepts that have been sketched out above. The book provides an overview of basic syntactic categories, analytical methods and theoretical frameworks that are needed for a comprehensive and systematic description and analysis of the syntax of English as it is spoken and written today. In addition, the book also wants to introduce the reader to the 'art' or science of syntactic argumentation. In some cases, therefore, a particular result may not be that important but the focus will be on the arguments that lead to this result. In those cases, the reader is invited to follow the argumentation and increase his or her awareness of pitfalls and possible alternative explanations. Introduction 5 The book falls into two major parts. Part I (chapters 1 to 6) focuses on syntactic analysis proper. This involves a general discussion of syntactic categories and methods used in syntactic analysis, as well as an introduction of a particularly useful descriptive apparatus for the analysis of syntactic structures; this apparatus is largely based on the framework suggested by Quirk et al. (1985) and covers all grammatical structures from the word level to the sentence level. Generally speaking, we can say that the first part of the book deals with syntax of the written norm of Standard English, and depicts syntax as a stable and largely invariant system. Part II (chapter 7 to 12) widens the scope and discusses various aspects of variation, instability and fuzziness in the syntactic system, including syntactic differences between writing and speech and stylistic variation in syntax. The second part will also put into perspective the relation between syntax and semantics, discuss whether and to what extent syntactic structures have meaning, and provide an overview of some major models and theories that have exerted an influence on the description and analysis of English syntax over the past few decades, including, inter alia, generative grammar and construction grammar. The book will conclude with an exploration of psycholinguistic approaches to the study of syntactic units, syntactic structures and syntactic processing. Almost all examples that you will find in this book are authentic language data drawn from two major corpora. namely the British component of the International Corpus of the English language (ICE-GB) and the British National Corpus (BNC). Since most of the examples are taken from the first corpus, the source just provides information on the text-document and the line in ICE-GB, e.g. 'sa1-006:130' instead of 'ICE-GB: sa1-006:130'. Tokens taken from the BNC are marked as in the following example: 'BNC-J13: 3398'. In some cases examples have been slightly altered, for instance shortened. For the sake of readability, such changes have not been marked in the text.

![The Word-MES Strategy[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007764564_2-5130a463adfad55f224dc5c23cc6556c-300x300.png)