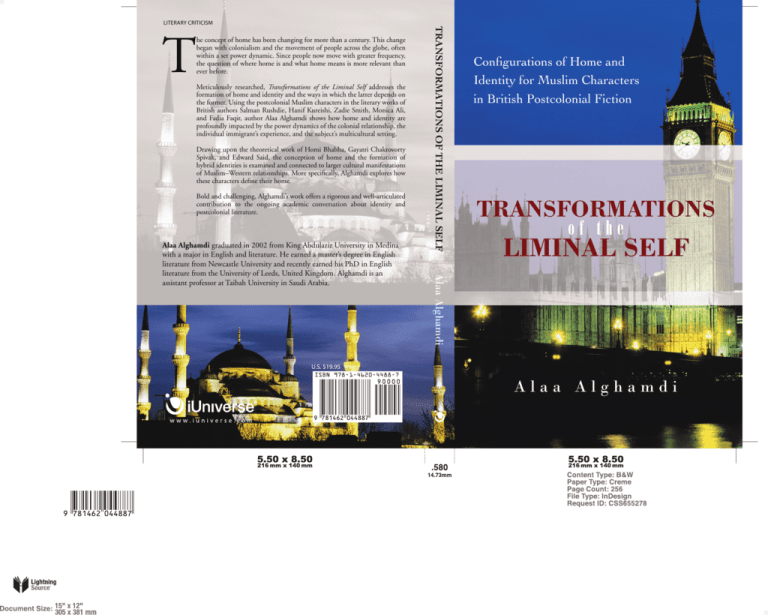

LITERARY CRITICISM

Meticulously researched, Transformations of the Liminal Self addresses the

formation of home and identity and the ways in which the latter depends on

the former. Using the postcolonial Muslim characters in the literary works of

British authors Salman Rushdie, Hanif Kureishi, Zadie Smith, Monica Ali,

and Fadia Faqir, author Alaa Alghamdi shows how home and identity are

profoundly impacted by the power dynamics of the colonial relationship, the

individual immigrant’s experience, and the subject’s multicultural setting.

Drawing upon the theoretical work of Homi Bhabha, Gayatri Chakrovorty

Spivak, and Edward Said, the conception of home and the formation of

hybrid identities is examined and connected to larger cultural manifestations

of Muslim–Western relationships. More specifically, Alghamdi explores how

these characters define their home.

Bold and challenging, Alghamdi’s work offers a rigorous and well-articulated

contribution to the ongoing academic conversation about identity and

postcolonial literature.

Configurations of Home and

Identity for Muslim Characters

in British Postcolonial Fiction

TRANSFORMATIONS

of the

LIMINAL SELF

Alaa Alghamdi

Alaa Alghamdi graduated in 2002 from King Abdulaziz University in Medina

with a major in English and literature. He earned a master’s degree in English

literature from Newcastle University and recently earned his PhD in English

literature from the University of Leeds, United Kingdom. Alghamdi is an

assistant professor at Taibah University in Saudi Arabia.

TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE LIMINAL SELF

T

he concept of home has been changing for more than a century. This change

began with colonialism and the movement of people across the globe, often

within a set power dynamic. Since people now move with greater frequency,

the question of where home is and what home means is more relevant than

ever before.

U.S. $19.95

Alaa Alghamdi

Transformations

of the Liminal Self

Transformations

of the Liminal Self

Configurations of Home and Identity

for Muslim Characters in

British Postcolonial Fiction

Alaa Alghamdi

iUniverse, Inc.

Bloomington

Transformations of the Liminal Self

Configurations of Home and Identity for Muslim Characters in British

Postcolonial Fiction

Copyright © 2011 by Alaa Alghamdi.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic,

electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information

storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of

brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

iUniverse books may be ordered through booksellers or by contacting:

iUniverse

1663 Liberty Drive

Bloomington, IN 47403

www.iuniverse.com

1-800-Authors (1-800-288-4677)

Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this

book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed

in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the

publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

Any people depicted in stock imagery provided by Thinkstock are models, and such images

are being used for illustrative purposes only.

Certain stock imagery © Thinkstock.

ISBN: 978-1-4620-4488-7 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-4620-4490-0 (hc)

ISBN: 978-1-4620-4489-4 (ebk)

Printed in the United States of America

iUniverse rev. date: 08/15/2011

Contents

Acknowledgement....................................................................... vii

Chapter One: Introduction...........................................................3

Chapter Two: Postcolonial Examination—

Foundations and Evolutions..................................................29

Chapter Three: The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie.................49

Chapter Four: The Buddha of Suburbia by Hanif Kureishi...........75

Chapter Five: White Teeth by Zadie Smith...................................99

Chapter Six: Brick Lane by Monica Ali......................................133

Chapter Seven: My Name is Salma by Fadia Faqir......................177

Chapter Eight: Conclusion........................................................213

Bibliography..............................................................................227

Acknowledgement

This book could not have been written without the help and support

of the following individuals.

I would like to express my indebtedness to my parents: to my father

for his unconditional support, and for being a perfect example for

me, and to my mother, who sacrificed so much for the sake of her

children, and for he constant prayers for me and for my success. I

likewise owe a debt of deepest gratitude to my uncle, Asem Hamdan,

who has been the prime source of inspiration in all venues of my

life. I am thankful for everything I have learned from him.

I am grateful to my sisters Mona and Rawan, who have always been

there for me, supported me, and encouraged me throughout my

research.

I am profoundly grateful for my sweet wife and best friend, Hadeel

Alsharif, for her unfailing encouragement, patience and support.

Finally, I wish to thank my friend and editor Malina Kordic, for her

tremendous help in making this publishing endeavor possible.

vii

Chapter One

Introduction: Home and Identity

in Postcolonial Perspectives

Chapter One: Introduction

Home and Identity in Postcolonial Perspectives

Of the multiple dilemmas that affect the postcolonial subject, the

interaction between home and personal identity is one of the most

pervasive and probably the most profound. Throughout much of

human history, one’s home was a fixed concept—stable, pure, and

intact. It is possible to see remnants of that placid and uneventful

conception of home and its affect on identity among members

of an intact culture, one in which there is little or no discernible

contrast between the individual and the larger society. Identity may

be attached to a certain geographical locale, and will certainly be

embedded within a culture. However, the disruption caused by

the colonial contact between cultures has had a long and complex

legacy, and the examination of home and its effect on identity is

central to the issues that emanate from this legacy.

Colonialism mixed cultures and set up an uneven power dynamic

between them. The concept of the Other, an individual living within

a society but always seen as belonging to it in a lesser or different

way, was created. Cultures have been permanently altered, leading

to a situation in which individuals, because of their race or cultural

history, are able to identify with some aspects of the society but

not with others. For all of these reasons, there has been a pressing

need to re-define the concept of home as it applies to members

of Postcolonial and multicultural societies in the twentieth and

twenty-first centuries. Home has become a contested concept, no

longer predictably applicable to a discreet geographic set of cultural

practices, given the formation of novel, hybrid and liminal positions.

3

Alaa Alghamdi

We must always question, therefore, what a Postcolonial subject

actually means when he or she speaks of ‘home’. In The Politics of

Home, Rosemary Marangoly George (1999) discusses, at the outset,

the imaginary properties of home for the Postcolonial subject,

noting that home is a “desire” for a stable, rooted identity, and that

realistic works of fiction reflect this by situating themselves “. . . in

the gap between the realities and the idealizations that have made

‘home’ such an auratic term” (George 1999: 2). George implies,

therefore, that the personal and social meanings of home have been

significantly altered, and that this change in turn can be extrapolated

and characterized—even if not precisely defined—from the works

of novelists who examine and represent the permutations of home

experienced by these subjects.

George notes that many scholars of the twentieth century (including,

for example, Gaston Bachelard, Clara Cooper, David Sopher, Yi-Fu

Tuan, Douglas Porteous, Adrian Forty and Witold Rybczynski) have

drawn a close correlation between home and self-identity (1999:

20). Both concepts are, however, malleable. When people occupy

a place over a long period of time, the experiences and practices

that emerge within it influence the self-identity of those who live

there. However, for subjects who have left or been parted from

their original setting self-identity may become fragmentary, divided

between identification with the older and newer setting. Home may

become ‘imaginary’ or ‘desired’, if the focus is on a union with a

setting and range of practices no longer accessible to the subject.

At the same time, of course, self-identity through the bonding with

a sense of home may be stymied by exclusion or marginalization

within one’s new social context and culture.

Identification with one’s home or homeland becomes complex

and problematic in the case of the exile or immigrant subject

because the homeland has been altered, left behind, or otherwise

inaccessible. Within this context, the examination of individual

identity formation relative to the notion of home becomes relevant

to virtually everyone in society. The intersection between the two

4

Transformations of the Liminal Self

can no longer be taken for granted. An examination of all aspects

of home and identity, for all subjects, becomes widely applicable to

literature and life. Our current and continuing movement towards

globalization merely increases the complexity of the interaction

between home and identity and renders it universally applicable.

A pure or stable notion of home may refer to one’s place and culture

of origin, but if the subject has left his or her homeland (either

voluntarily or through necessity) and has no direct access to it, this

construction of ‘home’ becomes less reliable. Its power may increase

even as its tangible qualities diminish. As one critic describes it, the

notion of home has extended beyond its “primary connotation . . .

of the ‘private space’ from which the individual travels into the larger

arenas of life and to which he or she returns at the end of the day . . .

home is also the imagined location that can be more readily fixed in

a mental landscape than in actual geography” (George, 1999: 11).

The idea of home can acquire more power in the absence of access

to the place itself, and this imagined construct has the power to

strongly influence issues surrounding the intersection of home

and identity. Constantly referencing an imagined homeland is

problematic for the Postcolonial subject if it creates nostalgia for

something inaccessible or if it serves to accentuate the alienation

of a subject from his or her immediate surroundings and culture.

In some cases, the family unit may be disrupted or fragmented due

to a member’s loyalty to an abstract notion of home or homeland.

The subject’s loyalty may be split due to a dichotomy between his

or her homeland and actual, physical home. The subject may also

experience discrimination or simply a lack of understanding in his

present environment, causing him to identify more closely with

the original homeland. In short, a great variety of possibilities exist

with regard to this complex interaction. Unlike a physical home,

the imagined home or homeland as an abstract concept transcends

time and space. The idea is powerful and pervasive, though its

definition and manifestation is highly variable. The power of the

imagined home or homeland may be central to an understanding of

5

Alaa Alghamdi

the Postcolonial subject with regard to his or her identity formation.

Specifically, in the immigrant or exiled subject, the ephemeral,

indefinite or imaginary construction of home and self-identification

with this imaginary notion of home ultimately impacts the subject’s

ability to form a hybrid identity. Postcolonial theory, understood

within the broader context of postmodern inquiry into identity and

other key concepts, provides a useful framework through which to

examine the immigrant or exiled subject’s formation of identity.

Accordingly, this research and analysis applies Postcolonial theory to

the examination of the home-identity interaction in the Postcolonial

subject of Muslim origin. Assuming for the moment that hybrid

identity formation is the objective for a Muslim character living

in and adjusting to a multicultural context, the identification or

over-identification with an ‘imagined home’ or homeland may

hold the individual back and prevent the evolution of identity. It is

equally important to acknowledge that, conversely, the identification

with the imagined or remembered home as a relatively stable entity

may also provide a unique foundation for the evolution of new

Postcolonial identities.

These questions are addressed through a juxtaposition of the

depictions of the search for home and selfhood in the works of

Salman Rushdie, Hanif Kureishi, Monica Ali, Zadie Smith, and

Fadia Faqir. Whether literal or symbolic, the notions of home and

identity warrant a re-examination within a Postcolonial theoretical

context, with the ultimate objective of explicating the nature and

result of the interaction between the subject and his or her new

and old, stable and shifting, lived and imaginary notions of home.

The identity that springs from the identification with these various

‘homes’ may be a liminal one, allowing the subject to straddle

various cultures and identities and create an innovative but fully

functional identity. In fact, it is the strength and variety of such

identities that reveals the resilience and promise of the Postcolonial

subject. Postcolonial inquiry, which once focused on the loss of

identity and the marginalization of minority subjects, may now

potentially transcend these concerns and examine the strong, novel

6

Transformations of the Liminal Self

and unique identity formation which does occur among liminal

subjects. Liminality and hybridity may come to characterize home

and identify formation the majority of individuals in the twenty-first

century.

The modern or Postmodern novel is the ideal forum in which to

explore questions of identity and home in the Postcolonial. Hanif

Kureishi considers the novel to be “the most capacious, the most

sensual form [of literature]”, capable of capturing and conveying

human experience in a multifaceted manner (“Hanif Kureishi

Interview”, n.d.). The French novelist Louis Aragon called the novel

“the key to forbidden rooms in our house” (cited by Faqir, 1998:

86), acknowledging that novels have a unique capacity to let the

reader into the subject’s home, space and work, and thus effectively

interrogate it. Moreover, novels have the unique ability to allow for an

examination of the subject in situ, embedded within and influenced

by a full complement of human, cultural and geographical contexts.

After all, self-identification cannot exist in a vacuum.

Novels are, moreover, excellent tools for promoting understanding

through the depiction of culturally and racially diverse subjects,

Postcolonial writers have added greatly to readers’ knowledge of,

experience with and empathy for the issues facing the potentially

fragmented subject attempting to acquire a cohesive and coherent

identity. In addition, novels are perhaps particularly well suited to the

discussion of Postcolonial subjects because they provide immediacy

and an ease of identification with the subject, erasing or diminishing

cultural divisions that may otherwise separate individuals within a

multi-cultural society. A reader who would not be able to identify

with a subject represented through statistics or other objective forms

of representation may readily identify with such a subject within the

rich context provided by a novelist.

For a writer dealing with themes that are related to Muslim culture,

the novel has a particular significance in that it provides a forum for

7

Alaa Alghamdi

the exploration of a shifting sense of social, political and religious

identity. Edward Said states:

The one place in which there’s been some interesting

and innovative work done in Arab intellectual life is in

literary production generally, that never finds its way

into studies of the Middle East. You’re dealing with the

raw material of Politics . . . You can deal with a novelist

as a kind of witness to something. (Middle East Report

1988: 33)

Said implies that it is through literary production that the subject

can be represented relatively free from external influence and foreign

contextualization or explication. Whereas supposedly objective and

unbiased non-fiction sources may carry and reproduce the bias of

the dominant culture, the novel (at least potentially, appropriation

issues notwithstanding) provides a forum in which the Postcolonial

subject can speak for himself or herself.

The Postcolonial subject’s identity is hybrid because it is based

on based upon multiple notions of home. The subject is a liminal

figure because he exists on the threshold of multiple realities,

navigating between them and potentially forming an identity based

on hybridity. While it is appealing, on a theoretical level, to present

such hybridity as strength, it can just as readily be experienced as

conflict and weakness, and evaluation of the subject’s position must

take into account a multiplicity of experiences. The formation of a

liminal identity as the result of the loss of one’s original home and

the need to adjust to a new one may even be liberating, as it may

free the subject to form novel and unique identities which carry

their own strength. Ultimately, both the positive and negative effects

of hybridity must be considered. Personal limitations cannot be

minimized or discounted; nor should they circumvent exploration

of the fertile possibilities presented by increasingly varied identities,

some of which have not been covered by prior literary criticism.

8

Transformations of the Liminal Self

This book attempts to demonstrate how the selected literary

texts promote an increasingly multifarious and resilient vision

of the Postcolonial Muslim subject’s identity. The subjects under

examination are both empowered and limited by the parameters

of memory, history, tradition, belief, and personal experience, and

sometimes reach unprecedented forms of cultural participation. A

study of these Postcolonial Muslim subjects allows us to analyse

closely the process and outcome of identity formation in cases

where that process is fragmented and outcomes are unpredictable.

The eventual formation of identity in these subjects is testimony to

the resilience and ingenuity of the characters as well as the authors

who create them.

Postcolonial theory and criticism support the notion that the

liminal position may be one of strength, creativity and promise,

notwithstanding the challenges associated with occupying such a

position due to displacement from one’s homeland. According to

some critics, alienation itself is a catalyst. Memory is identified as

the factor primarily responsible for the imaginary reconstruction

of home, but it is noted that: “Memory does not revive the past

but constructs it” (Hua, 2006: 198). For those separated from

their homeland, history, and language, marginalized and perhaps

discriminated against in a new environment, and forced to rely on

that inherently unreliable element—memory—to produce identity,

diverse and creative methods of constructing the self have become

necessary.

Poet Derek Walcott’s statement “I’m either nobody, or I’m a nation”

(Walder, 1998: 123) aptly describes the essential paradox inherent

in the expatriate’s search for identity. While identity might indeed be

fragmented, lost, repressed or irretrievable, or otherwise indicative

of loss or dysfunction, it may also be true that the Postcolonial

subject’s identity, once formed, is such a novel conglomeration of

disparate parts that the result is the production of a unique “nation”

of one, which flourishes in ways previously undreamed of.

9

Alaa Alghamdi

Immigrants, expatriates and exiles seem at an obvious disadvantage

with regard to their ability to evolve a sense of self and of home. As

the selected texts illustrate, when the move is to a new country with

a different religion, culture, and set of values, alienation from one’s

past and present surroundings may occur. Ultimately, there is a shift

in values, but this does not occur in a linear or predictable fashion.

The individual is subject to multiple and complex influences. As

one critical source states, “Identity is the product of history; on

the personal level, of memory . . . the sense of lack, or loss, of

living in a cultural vacuum, may [hold] back achievement”; there

is a drive, therefore, to “[forge] a new present and future out of

many pasts” (Walder, 1998: 121-3). Marginality in and of itself can

have a positive effect, driving subjects toward creative and novel

identity formation. This ‘creative energy’, once unleashed, takes on

multiple forms. Describing the work of Salman Rushdie and Chitra

Banerjee Divakaruni, a critic notes that these and other writers, in

constructing a transnational sense of identity,

. . . use constructs of magic or the ‘esoteric’ to transcend

traditional notions of geographical borders, boundaries

of time and space, and limitations of identity. They

propose magical spaces (and people) with which to

redefine human abilities and communication, and to

re-examine issues such as intercultural violence, ethnic

identity, and an individual’s responsibility for war.

Sacred, or what I will discuss in the context of the

novels in this chapter as a ‘magical’ space, allows for

alternative readings of both past and future (Grace,

2007: 117-18).

No longer contained within or limited by an intact history or set

of traditional, cultural and religious values, these authors and the

characters they depict may have unprecedented freedom to form

new identities, constructed from diverse elements of memory, social

realities, and individual and collective concerns. It is this potentiality

which is of most interest in our exploration of Postcolonial identity

10

Transformations of the Liminal Self

and homeland. Key characters in the primary works selected form

identities in distinct and diverse ways, within which common

themes may be observed.

Despite the commonalities noted, the diversity of characters

demonstrates the multiple—indeed, almost infinite—possibilities

that exist for identity formation in the Postcolonial era. Zadie Smith

and Hanif Kureishi’s works offer ample ground for comparison in

terms of voice, style and intended audience. Of course, Kureishi’s

comic slant ensures that the characters consist in part of strange

hybrids, some of them dysfunctional and ultimately unsuccessful

combinations of the two contrasting cultures. Kureishi’s first

novel, The Buddha of Suburbia, one of the earliest of the genre,

presents a portrayal of a Postcolonial subject whose navigation

through various personal and cultural influences results in a novel

and creative formation of identity and a sense of home, addressing,

in the process, multiple issues pertaining to the representation of

‘Other’ (specifically Asian) cultures. Zadie Smith offers us a variety

of characters, some of whom successfully create identity, though

some remain locked in opposing positions which limit them. Very

relevant to both of these works, as well as certain others, is the

distinction that some critics make between the ‘immigrant genre’

(i.e. narratives dealing primarily with characters who have voluntarily

immigrated) and novels dealing with characters who have lost their

original homes.

The ‘immigrant genre’ is “distinct from other Postcolonial literary

writing and even from the literature of exile, [though] it is closely

related to the two” (George, 1999: 171). There are profound

similarities regarding the loss of home and the construction of an

identity and identification with an ‘imagined’ homeland, or one

constructed from fragmentary and unreliable memory, because of

the distance imposed on the subject. As a result, “like the distance

that exile imposes on a writing subject, writers of the immigrant

genre also view the present in terms of its distance from the past and

future” (George, 1999: 171).

11

Alaa Alghamdi

The central issue, in fact, seems to be a loss of the continuity that a

stable and intact sense of home would provide. For subjects who exist

in essentially the same home and culture as their forefathers did, and

who expect this consistency to continue in future generations, time

moves along in a linear fashion, but there may be no consciousness

of a sharp division or distancing between past, present and future.

Elements of the past and present are, in a sense, within that subject’s

reach. On the other hand, for the subject who has been displaced,

either through his/her own choosing or involuntarily, there has been

a sharp, perhaps irreversible break between his/her own experiences

and those of his/her ancestors, to the same degree that home

influences experience and identity.

The past is irretrievable and there is a distance between it and the

present. Moreover, the life that future generations will forge in the

new country is largely unimaginable to the immigrant and exile;

thus, there is a perceived break in continuity from the future as well.

As George states, this element of distance is consistent in narratives

where the characters are immigrants and where they are exiles

(171). However, there are multiple distinctions; the ‘immigrant

genre’ being “marked by a disregard of national schemes, the use

of a multigenerational case of characters and a narrative tendency

towards repetitions and echoes (through several generations)”

(George, 1999: 171).

Thus, even though the characters typically experience separation, it

is the tendency of the writer to follow characters through multiple

generations, perhaps in order to compensate for and derive meaning

from and a sense of completion in the narrative, which cannot, in all

cases, be accomplished within the history of a single generation.

While the effects of immigration are multigenerational, George also

notes that “the immigrant genre is marked by a curiously detached

reading of the experience of ‘homelessness’ which is compensated for

by an excessive use of the metaphor of luggage, both spiritual and

material” (George, 1999: 171). This is noted with regard to many

12

Transformations of the Liminal Self

of the selected narratives, particularly those of Smith and Kureishi.

For example, humour is a potent form of detachment.

The interrogation of home and identity in the novels is influenced

by formal aspects of the novels themselves. Brick Lane by Monica

Ali, being traditional as opposed to postmodern in structure,

demonstrates identity formation in a more subtle manner while

expressing many of the same characteristics described above.

Characters are displaced and alienated, and selectively adapt to

elements and values that were foreign to them at the outset. At the

same time, this adaptation generally does not consist of a rejection

of traditional Islamic values, but a subtle adjustment. Here again,

the influence of an absent homeland constructed through memory

is shown to contribute to the subjects’ identity formation. Liminal

subjects in Salman Rushdie’s and Fadia Faqir’s novels, on the

other hand, point out the potential limitations of hybrid identity

formation. The principal characters in My Name is Salma and The

Satanic Verses are ones who achieve and ultimately lose the hybrid

identity, displaying its vulnerabilities and fault lines.

Understanding Postcolonial concepts requires a thorough exploration

of the key conceptual frameworks relevant to the colonial voice

and genre. Colonial relationships have a very long history, perhaps

as long as the Eastern/Western relationship itself, as Europeans

throughout classical times (in particular during the Roman Empire)

conceived of a ‘need’ to conquer territory and spread aspects of their

culture and civilisation.

After the fall of the Roman Empire in the West, the opposition

between the Christian West, the Muslim East, and the Byzantine

culture which brought a unique construction of Western thought

into Eastern territory became a crucible for the formation of

oppositional identities and the competition for territorial and

ideological control. The Crusades, popularized as an effort to ‘regain’

the Biblical territories for the Christian West, clearly conflated

the notions of territorial and ideological control, which did not

13

Alaa Alghamdi

subsequently diminish. As Edward Said proposes, the opposition

between the East and the West and the Western construction of an

exotic Other, the ‘Oriental’ persona, became a fundamental part of

Western self-identity (Said 1978).

Stemming from this ideological foundation, and augmented

by the colonial era and British supremacy of the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries, colonial thought subjected the differences

between cultures to a clear value judgment. Western standards,

thoughts, customs, technology and behaviour were a dominant

norm, providing a seeming moral justification for the takeover of

supposedly less civilized territories. The colonial relationship was

always based on an uneven power dynamic and an exploitation of

the colonized country by the colonizer.

Imaginative rhetoric attempted to conceal, transform or justify

the unequal power relationships wrought by colonialism. For

example, colonizers sometimes conceptualized themselves as

parents to the supposedly less developed and more primitive

colonized population. Much of Christian rhetoric carried with it

a moral imperative to evangelize the ‘heathens’ of the East, who

would suffer the punishments of hell without the intervention of

the colonizer. The notion of the “white man’s burden” (Easterly

2006) racialized colonial relations, linking race and culture to the

ultimately self-serving desire of the white Western colonizer to make

colonized cultures and people more like their own. The use of the

word “burden” implies that this is a sacred duty rather than an act

of violence or oppression.

Following the end of the Second World War, however, the

weakening of colonial powers resulted in liberation movements

and a nationalist identity in many former colonies. The resulting

creation of Postcolonialism as a cultural consciousness and field of

study began with the re-examination of fundamental relationships,

includes seminal works by Edward Said, Homi Bhabha, Gayatri

Spivak, and others. Arguably, though, Postcolonial interrogation

14

Transformations of the Liminal Self

did not spring out of the void, but was necessarily predicated upon

the works of Michel Foucault, the first to identify and interrogate a

culturally constructed identity.

Foucault initiated the view of identity as a manufactured or

constructed thing rather than an essential and therefore unchanging

description of the inborn characteristics of a person or culture.

In Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1,

Foucault observes the ways in which a set of cultural practices and

social institutions have been instrumental in shaping identity, but

notes that these elements are often not recognized even by those

who are affected most powerfully and directly by them. This

observation led Foucault to develop a “genealogical” examination of

history—genealogical in that it engaged directly with the genesis or

origin of elements that we might take for granted otherwise. Thus,

we are able to examine “the present time, and . . . what we are, in this

very moment” in a way that tends to “dissipate what is familiar and

accepted” and concentrate, instead, on what is behind the original

formation of norms (Foucault, 1988: 265).

A distinct form of social critique grew out of this genealogical

enquiry, the ultimate objective of which is to analyze “the historical

limits that are imposed on us” with the possibility of one day going

beyond them (Foucault, 1984: 50). The trajectory between these

enquiries on the part of Foucault and modern Postcolonial analysis

is quite evident. Although Foucault’s philosophy has more often

been applied to issues of gender, the Postcolonial enquiry into

identity and the relationship between marginalized and dominant

cultures clearly stems from Foucault’s original enquiries. If identity is

constructed, there are traceable reasons behind the attitudes, beliefs

and behaviours perpetuated by an individual, community or culture.

Things that appear ‘natural’ or ‘instinctive’ due to their ubiquitous

presence are in fact constructions, deliberate or otherwise. This most

basic enquiry into the nature of identity gave rise to a comprehensive

Postmodern examination of all social relationships and positions;

for example, feminist analysis and gender studies grew up alongside

15

Alaa Alghamdi

Postcolonial studies, presenting a parallel analysis with a similarly

stringent enquiry into why we are who we are, stripping away even

the most seemingly inborn characteristics and holding them up for

analysis.

In Orientalism (1978), Said examines the cultural and identity

differences between East and West, noting that both are created and

exaggerated through the creation of an ‘exotic’ Eastern or Oriental

identity, and opposition or disparity which in turn allows the West

to self-identify. Thus, Orientalist scholars cultivated an image of the

East as “irrational,” “depraved,” “childlike” and “different” (Said,

1978:40). In contrast, the West characterizes itself as “rational,”

“virtuous,” “mature,” and “normal”, the antithesis of all that is

Oriental (Said, 1978: 40). Of course, to those who identify with the

East as a real or imagined ‘homeland’, Orientalism may become a

mediating factor preventing a true experience of home. To those who

identify with the West, this view of the ‘Orient’, if left unexamined,

is perpetuated and continues to divide and define a hybrid and

diverse culture. For Postcolonial subjects who find themselves living

in the West and attempting to construct identity based on a hybrid

notion of home, internalizing this deeply embedded standard will

inform and, indeed, skew their perceptions, greatly problematizing

the development of an authentic sense of home, homeland, identity,

and belonging.

In several seminal works, Homi Bhabha emphasizes the importance

of social power relations in his working definition of subaltern

groups as “oppressed, minority groups whose presence was crucial

to the self-definition of the majority group: subaltern social groups

were also in a position to subvert the authority of those who had

hegemonic power” (Bhabha quoted in Chambers and Curti, 1996:

210).

In his 1994 book entitled The Location of Culture, Bhabha

concludes that, in the West, there is a need for us to shift towards a

“performative” and “enunciatory present”. This is seen by Bhabha

16

Transformations of the Liminal Self

as a necessary basis for fewer violent interactions and a decreased

compulsion to colonize those who are viewed as ‘Other’. In The

Location of Culture (1994), Bhabha investigates hybridity as a source

of ambivalence and anxiety in the individuals who are assumed

to have power within the colonial relationship. This observation

implies that hybridity challenges the established parameters of

the Postcolonial relationship between dominant and dominated

subjects. In a sense, all of Postcolonial theory and literature brings

us beyond the binary of dominant/marginalized identities. In the

end, in doing so, Postcolonial theory almost inevitably ends up

questioning itself and its own founding precepts.

The need for this questioning becomes more apparent as one delves

deeper into Postcolonial theory. After all, the process of questioning

identity and representation is not a finite process, but ideally becomes

a lens through which we can examine all cultural voices and practices.

Such examination must indeed include a stringent interrogation of the

very voices that initiate scholarship. Thus, in her 1988 essay entitled

“Can the Subaltern Speak?”, Gayarti Chakravorty Spivak seriously

questions whether the ‘subaltern’—the marginalized individuals

and populations—have a voice that can be heard by others in the

world, or whether that voice has been interpreted and appropriated

by western scholarship. Spivak takes as her example the women in

India who practiced ‘sati’, a tradition wherein a widowed woman

would climb onto her husband’s funeral pyre in a form of suicide,

seemingly indicating that the woman’s life, in and of itself, had no

value. The practice is decried and considered, quite understandably,

the epitome of marginalization and devaluation of women’s lives.

However, as Spivak (1988) points out, one never hears the voices

of the women who actually participate in this practice. We know

next to nothing about their feelings, experience, or rationale. The

Western academic world is much quicker to speak up in defence

of these women than it is to hear them. This, Spivak argues, is an

oversight which is difficult to overcome because it undermines the

established foundations of scholarship. On the other hand, failing

17

Alaa Alghamdi

to question these foundations merely reproduces the colonial power

imbalance, albeit in a different form.

Postcolonial criticism, in its most basic and fundamental distillation,

leads us to question the basis and formation of individual and social

identity and the relationship between various identities. ‘Identity’,

in this sense, can be said to encompass collective beliefs and

practices that seem intrinsic to the individual or the larger culture.

Once the enquiry into identity was begun, it became necessary for

it to continue, as each examination yielded evidence of the legacy of

unequal power relationships between individuals and cultures.

The most current critiques of the work of Foucault, Edward Said,

Spivak and other Postmodernist or Postcolonial scholars point out

that the tendency to ‘essentialize’ is even more difficult to strip away

than may be initially imagined. It has been noted, for example, that

the societal and cultural disciplinary power envisioned by Foucault

tends to assume the disempowerment of those who are subject to it.

Foucault’s analysis may tend to homogenize the response to cultural

coercion and hegemony, and conceptualize no way in which a

subjected individual can escape or gain power. Said’s concept of

Orientalism, likewise, is currently controversial in that, according

to his critics, Said himself (given his Western education) may not be

equipped to examine the Orientalized subject.

Yet such critique in and of itself may tend to assume that the subject

in question has immutable characteristics and predictable responses

to his or her own subjugation. Again, in order to even attempt to

understand these subaltern characters, the assumption is made that

they must possess a finite and defined set of characteristics. The

examination of power sometimes seems to preclude both individual

variations in the experience of and response to that power and the

formation of novel identities which challenge rather than capitulate

to the imbalance of power, yet this is precisely the trap that one

must avoid falling into. Within queer theory, an offshoot of feminist

studies, and the enquiry into socially constructed identities, the

18

Transformations of the Liminal Self

personal label ‘queer’ is used to indicate not an identity per se, but a

critique of identity. A person may self-identify as queer if he or she

does not accept or wishes to critique the sexual identity that society

transmits (Jagose 1996). One thing that has become abundantly

clear during the preceding enquiry into identity among Postcolonial

subjects is that there is a need for an equivalent label among those

who do not accept and wish to interrogate the basic precepts of

cultural identity. Such a label would be a convenient shorthand for

expressing a rather complex idea or set of ideas. Moreover, it could

apply not only to those who are forced into a position of enquiry

by their social or cultural displacement or alienation, but also those

who consciously choose to undertake an enquiry of cultural identity,

thus building solidarity between Postcolonial subjects and critics.

The creation of novel and innovative identities that do not necessarily

fit any existing mold is the focus of this research, and one of the key

areas of interest in modern Postcolonial thought and criticism. The

promise lies in bringing these elements into balance, recognizing

coercive power and cultural hegemony while appreciating the

distinct qualities of every individual. Otherwise, this analysis may

tend to erase differences between individuals, and, even worse, it

may limit or underestimate the individual’s capacity for redefining

the relationship with power and forming novel identities.

In the realm of politics and society, the need to interrogate cultural

identity and its attendant stereotypes is currently reaching a crisis

point. The position of Muslims in Western societies has changed

significantly in the years since September 11, 2001, but the changes

are more complex than is sometimes assumed. The increase in

‘Islamophobia’ is one generalized reaction to the 9/11 terrorist

attacks in New York City.

The term Islamophobia is sometimes used to describe the attitudes

of non-Muslims towards Muslim citizens of European countries.

Although the term was coined as far back as 1922 (Cesari 2006),

it is finding new application since 9/11. Although the term is

19

Alaa Alghamdi

criticized in academic circles because it is imprecisely applied, it

is an apt term, predating current concerns about terrorism and

originally encapsulating a generalized xenophobia and the conflicts

between the Christian and Muslim worlds that have occurred since

the Crusades of the Middle Ages. Discrimination against Muslim

people in the West existed before 9/11; for example, American

studies dating from the 1980s and 1990s reveal broad-based social

and professional exclusion of Muslim citizens from high-ranking

professional and civic positions (Cainkar n.d.). These same studies

reveal that the situation was improving by the 1990s, only to

suffer a huge setback following 9/11. However, the discrimination

against Muslim people prior to the 9/11 terrorist attacks was often

not recognized as such. Demographically, these individuals were

“hidden under the Caucasian label” (ibid) and this sometimes

minimized their marginality, or the perception of it. The biggest

shift, therefore, since 9/11 was that the Arab populations of

Western powers suddenly became visible, as did acts of racism

perpetrated against them. In the period immediately following the

terrorist attacks, 645 ‘bias incidents’ and hate crimes against Arabs

and South Asians were reported in the US. A mosque was attacked

in Chicago the following day, followed by near-continuous attacks

against Muslim-based organizations and buildings (ibid).

The resurgence of the term ‘Islamophobia’ in this new historical

context post-9/11 is not the only example of the resurrecting,

sometimes conscious, of an antiquated terminology. As reported by

BBC journalist Barnaby Mason in the week following September

11, 2001, US President George W. Bush specifically referred to the

war on terrorism as a ‘crusade’, much to the consternation of British

Prime Minister Tony Blair. Bush’s statement ran directly counter to

Blair’s stated objective of preventing the framing of the 9/11 attacks

and the ensuing international conflict as a war between religions.

The mention of the crusades—historical wars waged by Christians

against Muslims—was problematic on several levels.

20

Transformations of the Liminal Self

The medieval crusades were exploitative wars whose objective was

to gain control of the ‘holy lands’ in the East, and as such involved

an invasion of foreign territory. Naturally enough, the term was

distressing to people in Muslim countries based on the historical

episodes it refers to. Moreover, in its common usage, the term crusade

implies a righteous war—literally a war in the name of the Cross, or

in the name of God. As Mason implies, it is this latter application,

in its generalized sense, that President Bush was invoking; his likely

meaning being that the war on terrorism is a just or righteous war.

However, in using such a historically loaded term, the ‘righteous’ or

‘just’ conflict against terrorism is easily identifiable as a war against

Islam itself, just as the original crusades were.

Whether or not Bush was fully cognizant of how “full of historical

resonance in Europe and the Middle East” (Mason 2001) the term

he employed was, his statement was potentially very damaging to the

perception of Muslims in the West. A world leader had effectively

cast them as the parties on the ‘wrong’ side of a ‘holy’ or righteous

conflict. The effects of this vilification were ultimately felt in Europe

as well as in the United States, lending credence to the unfortunate

possibility that this was, indeed, a war between civilizations.

In Europe, the after-effects of the 9/11 terrorist attacks with

regard to their impact on Muslim populations have been almost

as dramatic as in America, and arguably even more far-reaching.

A 2006 British study of 222 British Muslims (Sheridan, 2006:

317), for example, showed a sharp increase in both indirect/implicit

discrimination and overt incidents of harassment or discrimination,

the latter having risen by 76.3% since 9/11, and the former by

82.6%, as reported by the affected individuals themselves (ibid).

These findings demonstrate, according to Lorraine Sheridan, that

both active discrimination and more passive or less perceptible

stereotyping have both increased dramatically in the years following

9/11.

21

Alaa Alghamdi

Stereotyping can have a pernicious effect on individuals that is as

disruptive to the formation of identity and a sense of belonging

as direct discrimination can be, precisely because it is subtle and

pervasive. The analysis of these findings includes the observation

that religion is a more significant factor in discrimination post-9/11

than race or ethnicity. This observation supports the notion that

Muslim minorities were ‘invisible’, or that they hid behind the

“Caucasian label”, prior to the 9/11 attacks. One wonders, however,

how this translates into practice, as religion is not always a quality

as race and ethnicity might be, and incidents of discrimination

against Muslim or Arab populations are not limited to those visibly

engaged (because of style of clothing, for example) in a specific

set of religious practices. If it is the case that religion (essentially,

‘Islamophobia’) rather than race or ethnicity motivates xenophobic

attacks, that distinction is nevertheless of little value to those who

find themselves under attack.

In the United States, where the 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred,

the drive towards increased homeland security has resulted in the

suspension of civil liberties for some Muslim and non-Muslim

individuals and groups. In Europe, the legislative aftermath of the

attacks has possibly been even more far-reaching. Liz Fekete (2004:

3) calls it an “attack on civil rights” directed at Muslim Europeans.

Governments have taken measures to step away from a multicultural

model or objective for their populations. Instead, assimilation and

‘monoculture’ are promoted (Fekete, 2004: 3). This is discernible

in several integration measures that countries have undertaken; one

example is the banning of the headscarf in France (Fekete, 2004: 3).

As of spring 2011, the French government will enact an ‘anti-burka’

law, making it illegal to cover one’s face in public by wearing a burka

or a niqab. These traditional garments, worn by women, conceal

the head and body, with an opening only for the eyes. The French

objection to wearing the burka or niqab references both security

and a concern about the discrimination of women under strict

Islamic law; however, it is perhaps particularly significant that one

22

Transformations of the Liminal Self

proposed consequence of breaking the proposed law is enrolment

in a citizenship course (Litchfield 2010), clearly implying that this

traditional garb is considered detrimental to the formation of one’s

identity as a French citizen.

However, it is also worth noting that the penalty for “‘forcing’ a

woman to wear a full-face veil” is exponentially harsher than the

penalty for actually wearing one (Litchfield 2010), giving some

credence to the idea that the law is meant to protect women.

Measures such as these are naturally controversial; in a sense,

regardless of the government’s motivations in promoting measures

like these, they are problematic by their very nature because they

make religious expression an item for public discussion and debate,

forcing Muslim populations to defend these aspects of culture and

faith, whereas less-visible (in other words, Christian) expressions

go unnoticed and are never open to debate. If, as Sheridan finds,

discrimination against Muslims in Europe is indeed more a matter

of religion than one of race or ethnicity, it only serves to make the

discrimination that is suffered more likely to become entrenched in

society through legislation. It may be impossible, in this day and age,

to legally discriminate on the basis of race, but religious practices

are considerably more vulnerable, and may be just as integral to

citizens’ sense of identity.

The more subtle effect of these changes since 9/11 is that they

constitute a threat to many of the strides that have been taken

with regard to the development of a hybrid culture where

multiculturalism becomes the norm. During the 1990s, particularly

in major cosmopolitan cities such as London, the melding of

cultures was producing a society in which the creation of an ‘Other’

was, though not eliminated, at least minimized. The drive towards

assimilation—both internal and external—directly counteracts

this trend. The immigrant subject may be able to establish an

identity based on the awareness of home in a multicultural society.

If multiculturalism is “rolled back” (Fekete, 2004: 3), identity

formation becomes, once again, a matter of opposition rather than

23

Alaa Alghamdi

integration. Sheridan (2006: 317) notes that, post 9/11, 35.67% of

the British Muslims surveyed suffered mental-health issues, most

often related to abuse or discrimination (Sheridan, 2006: 317).

The difficulties in forming identity are extremely far-reaching and

ultimately harmful for these individuals; the inequities of the colonial

system are echoed and magnified. Adopting as its foundation the

theoretical framework and reference to historical events introduced

in this chapter, this study assumes that Postcolonialism is based on

the experience of movement between cultures and geographical

areas, and the consequent experience of adjustment following the

loss of one’s original home or homeland.

New identities are formed through this process, along with new

conceptualizations of home. Leaving their homeland in order to

search for an adopted home, individuals may become (and regard

themselves as) exiles or immigrants, and they may have a personal

desire to either adhere to the customs and practices of their lost

homeland (sometimes harbouring a desire to return to that

homeland), or to assimilate to the standards of their new home. In

either case, however, the end result is commonly a hybridization of

identity, with elements taken from both cultures. The hybrid identity

can be, variably, a position of strength and/ or of vulnerability.

There is, of course, a distinction to be made between the immigrant

who has voluntarily left his home and the exile that has been forced

to leave.

As outlined previously, the dissimilarities are profound enough for

the ‘immigrant genre’ to be considered separately from the stories of

other types of ‘moving’ subjects by some critics.

However, the similarities can be profound, particularly with regard

to the question of losing one’s home, homeland or sense of home.

Andre Aciman brings unity to the two terms, arguing that an exile

is not always defined as “someone who has lost his home”, but may

also be defined as “someone who can’t find another, who can’t think

of another” (21). This may be common to all Postcolonial subjects

24

Transformations of the Liminal Self

who have left their countries of origin. On the other hand, it may

also be argued that the immigrant, at any rate, has some control over

the situation and may have come to the new home in the process

of exercising a positive choice. Moreover, the immigrant may have

a heightened tendency to harbour a desire to ‘return home’, given

that the home was left voluntarily and may presumably be returned

to voluntarily as well.

Novels dealing with immigrants (sometimes referred to as the

‘immigrant genre’ of novels) do indeed show a tendency to assimilate,

but with a marked difference between generations. The particular

plight of the second-generation immigrant, born in the new country

but remaining tied to the old because of cultural heritage as well as

possible exclusion, is sometimes even more difficult than that of

the first-generation immigrant. There is, also, an increased demand

for and possibility of such a subject forming a hybrid identity, or,

conversely, of failing in the attempt to do so. According to Stewart

Hall, displaced subjects feel the need to constantly “produc[e] and

reproduc[e] themselves anew through transformation and difference”

(Hall, 2008: 402). It is these transformations and differences which

will become the main focus of this research. Postcolonial subjects

take various routes to hybrid identity formation, some predictable,

others anything but.

The tacit objective of all of these characters seems to be the formation

of an identity which adequately covers the complexities of their

characterizations and allows them to participate meaningfully in

the society within which they find themselves. Some characters are

successful in this endeavour, others much less so. It is in the course of

examining these successes and failures that the influence of colonial

and Postcolonial cultural values will be examined. Moreover, the

ways in which the characters (successfully and unsuccessfully)

transcend and transform the values and norms of their old and new

cultures in the process of hybrid identity formation forms a basis

for beginning to define and examine the ongoing transformation

brought about by both the rise and the fall of colonialism.

25