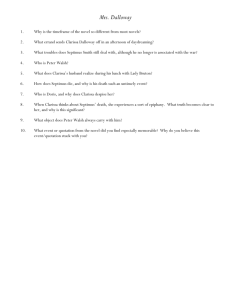

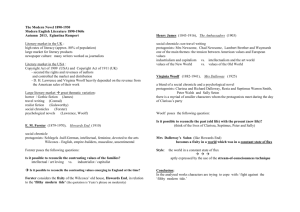

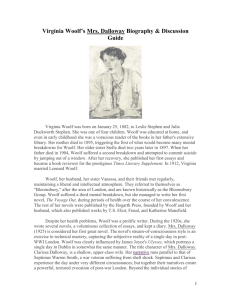

Accessorizing Clarissa: How Virginia Woolf

advertisement