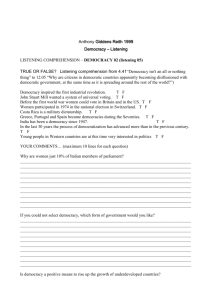

Liberalism, Marxism, and Democracy The End of

advertisement