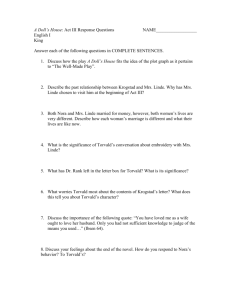

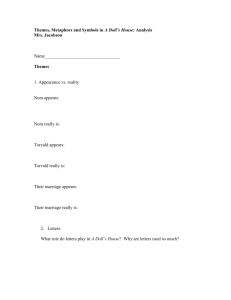

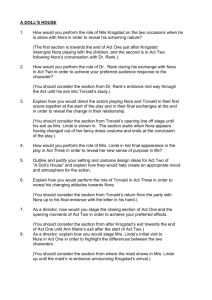

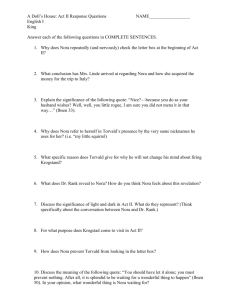

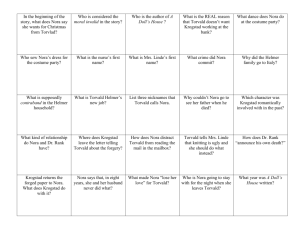

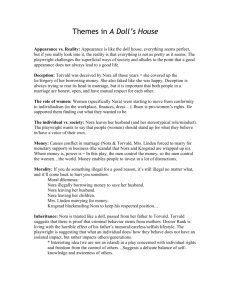

A Doll's House - English@Turton

advertisement