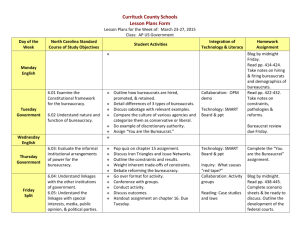

The politics-bureaucrac - Developmental Leadership Program

advertisement