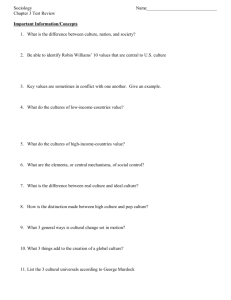

In re Dole Food Co., Inc. Stockholder Litigation

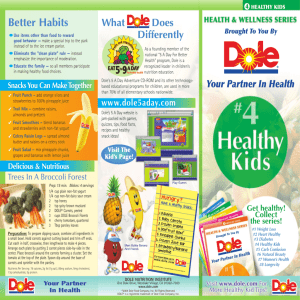

advertisement