Sir Lancelot: The Paradox at the Heart of King Arthur's Court

advertisement

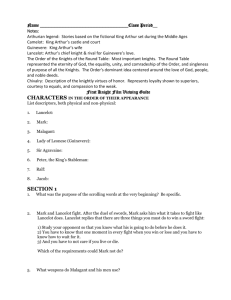

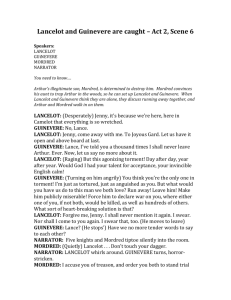

Pavel Goriacko ENG650 Research Paper Sir Lancelot: The Paradox at the Heart of King Arthur's Court In Arthurian romances of the twelfth century and after, Lancelot is undoubtedly one of the most renowned knights of The Round Table. Lancelot's character is central to the plot of Chrétien's The Knight of the Cart and Malory's The Poisoned Apple, Lancelot and Elaine, and The Death of King Arthur. These texts make it evident that Lancelot isn't merely a knight; rather, he is the greatest knight of The Round Table. The court depends on Lancelot and his prowess, as he constantly stands up to defend the queen against accusations and takes up challenges which are too great for other knights. Yet Lancelot's identity as the most powerful knight is completely dependent on his rejection of the ideals of the court and his illicit relationship with Guinevere. Thus, the very existence and success of King Arthur's court rests upon an illicit relationship and a system of ideals contrary to the one it upholds. Origins of Lancelot The character of Lancelot is first mentioned in Chrétien's The Knight of the Cart, although the immediate literary ancestor of Lancelot is a hero in the stories of “The Fair Unknown.” In Lancelot and Guinevere: A Casebook, Lori Walters explains that “The Fair Unknown” is a story “in which a young man, brought up in ignorance of his name and origin, is called the 'Fair Unknown' when he arrives at Arthur's court” (Introduction xiv). As Chrétien is the first to distinguish Lancelot from the “Fair Unknown,” it is no wonder that he had the most influence over the identity of Lancelot, especially in “stamp[ing] him in popular consciousness as the queen's lover” (Walters Introduction xiv). Robert W. Hanning argues that Lancelot is one of the primary examples of the development of a subjective voice in romance literature in the twelfth century. Quoting Norman F. Cantor, Hanning writes that “in the twelfth century there emerged a new consciousness of the self and recognition of the importance and distinctiveness of the individual, marking a significant departure from the group and typological thought of the early Middle Ages” (Hanning 2). From these early developments, we can see that solitude and individualism were the basis for the character of Lancelot from the time of his creation, as he is the product of a modified “Fair Unknown” story emerging during the time of high interest in personal subjectivity. Furthermore, Lancelot's origin and upbringing are in line with his outsider nature. He comes to England from France and wins the admiration of the Round Table, much like the “Fair Unknown.” This becomes important when in Malory's The Death of King Arthur, Lancelot and his supporters split from the court and move back to France. Lancelot's upbringing consists of being raised by the Lady of the Lake (Chrétien 2350-2355), which indicates that his childhood was dominated by a female presence. This begins to explain his unconventional relationships with and dependence on women. Arthur, on the other hand, was brought up and trained by Merlin, and Gawain is the son of Loth of Lothian (Harper), which indicates that both of them were forged by a dominant male presence in their childhood. They also share a nephew-uncle relationship, whereas Lancelot, as mentioned earlier, is a stranger in England and has no relatives there. Lancelot's background then becomes an early indication of the his unique character traits, particularly pertaining to relationships with other knights at the court. The Homosocial Court From the very beginning in The Knight of the Cart, Lancelot is introduced separately from the other knights at Arthur’s table. When Arthur holds court and festivities, Lancelot isn’t there (ll. 30-34). Due to his absence, he cannot participate in the argument at the court over who is most worthy to escort the queen to the woods (170-178). This immediately portrays Lancelot as a very introverted character who excludes himself from homosocial gatherings and arguments. Gawain only meets Lancelot after riding off to follow Kay and finding Kay's horse spotted with blood (261-265). Lancelot already knows what happened to the queen. However, unlike the other knights, Lancelot is not motivated by glory or duty to rescue her; he is driven to it by love. This shows us that Lancelot puts the heterosexual obligation of rescuing his lover over the homosocial obligation of winning glory among his fellow knights or supporting his lord. His introversion also highlights the lack of a homosocial bond between him and the other knights. In contrast, Arthur and Gawain have a strong homosocial bond. When Kay goes off to bring the queen into the woods, Gawain advises Arthur to follow them. Arthur replies, “We’ll go, good nephew... / Yours is a politic wisdom” (238-239). This shows that Arthur’s decision to follow the queen is motivated by his nephew’s advice rather than his own obligation to protect and take care of his wife, and thus highlights the importance that Arthur places on the homosocial bond with Gawain. On the other hand, Kay’s exclusion from court leads to his desire to affirm his skill and glory; he fulfills it by tricking Arthur into letting him take on Méléagant’s challenge. Even though Kay is excluded from the homosocial company when Arthur holds court (as he is not there when the knight challenges Arthur), he still places great importance on his homosocial relationships. Kay wants to win recognition from the other knights and aspires to a place in court next to Arthur. He cannot embrace his exclusion from the court because unlike Lancelot, Kay has no heterosexual obligation to fulfill. Instead, he tries to save his homosocial bond with Arthur and his knights by attaining recognition among them. Gawain has no heterosexual obligations either; thus, he is portrayed as a very noble and chivalrous knight who is very active in homosocial gatherings. The Introverted Knight Further throughout the poem, Lancelot is portrayed as a solitary character who takes on challenges individually as opposed to Gawain who always takes fellow knights and squires with him. Right after Gawain persuades Arthur to send knights after the queen, Chrétien writes, ...Gawain Was fully armed, and had ordered Two of his squires to bring A pair of battle horses. (253-256) Later, when Gawain and Lancelot ride together and reach the two roads leading to two different bridges, Lancelot refrains from conversation with Gawain. He only says, Sir, it’s up to you: Pick whatever route You prefer; I’ll take the other (684-686) This highlights the impersonal nature of Lancelot’s relationship with Gawain, which lacks the strong homosocial bond that Gawain and Arthur share. It also reveals Lancelot’s desire to take on the challenge individually. Lancelot is willing to take the harder path as long as he can go alone. In Malory's King Arthur and His Knights, Lancelot is also portrayed as a solitary knight. When Lancelot finds out that the woman he slept with was Elaine and not Guinevere, he becomes mad and runs away to hide from the court. As Malory puts it, “he ran two year, and never man had grace to know him” (84). It's also important to note that his face and body are scratched with thorns, so he is unrecognized by others, which brings up the motif of obscured identity. Even when he awakes out of his madness, Lancelot is reluctant to return to the court, as he says to Dame Elaine, ...go ye unto your father and get me a place of him wherein I may dwell? For in the court of King Arthur I may never come. (Malory 94) While eventually Lancelot is convinced to return to the court, from his madness fit we can clearly see the desire present in him to avoid the court and its company. He particularly desires to be free from the social constructs and judgment of the court, as is evident in one of the first questions he asks upon awakening from his madness: “If this be sooth, how many be there that knoweth of my woodness?” (Malory 93), and further asks to “keep it counsel and let no man know it in the world” (94). Instead of desiring support and sympathy from the knights, he mostly desires privacy and secrecy. This once again reinforces the introversion of Lancelot’s character. In “The Poisoned Apple,” Lancelot is banished from the court by Guinevere, which once again puts him into solitude, as Malory says, “the queen had forefended him the court, and so he was in will to depart into his own country” (115). Lancelot only returns to the court to save Guinevere from being burned. This episode shows that Lancelot cares little about the other knights at the court and only stays there for Guinevere. Reliance on Women Lancelot's introversion and absence of the court frees him from many of the court's constrains. Thus, he is able to do certain things which would be frowned upon in the masculine company of knights. This quality shapes Lancelot’s relationships with women. On most of his adventures, Lancelot encounters damsels. However, despite his attempts to simply protect and safely accompany the damsels, he ends up needing and receiving help from them which his fellow knights cannot provide. When Méléagant imprisons Lancelot for the first time, the steward’s wife lets him out of prison as long as Lancelot agrees to return (Chrétien 5468-5513). The second time Lancelot is rescued from prison by a woman as well; this time it’s Méléagant’s sister. The reader expects Lancelot to be rescued from his imprisonment in the tower by Gawain or another knight, and so does Lancelot himself, as he says, You great Gawain! Unmatched For your goodness, how can it be You haven’t come to help me! (Chrétien 6494-6496) However, Gawain is told that Lancelot has returned to the court and thus does not show up to the rescue. When Méléagant’s sister comes to rescue Lancelot, she says, Lancelot, I’ve come A long, long way to find you. ... I was the one, as you rode Toward the Bridge of Swords, who asked you To grant me a wish, and you did, Most cheerfully. Recall: I asked for the head of the knight You conquered, and you cut it off. He was not someone I loved. I’ve gone to all this trouble Because you granted that wish. (Chrétien 6577-6589) From this we learn that the damsel comes to rescue because a little while back Lancelot granted her a wish. Yet in granting that wish, Lancelot had to choose between showing his opponent mercy and letting the damsel have the knight’s head. Lancelot’s choice to give the knight’s head to the damsel is a violation of chivalric code and his own beliefs, as the poet says “Once the battle / Was won, and his enemy beaten, / He’d never refused mercy / To anyone, no matter who --- / Never” (2859-2863). However, Lancelot does it because he is not constrained by his homosocial obligations. Lancelot’s actions are not motivated by upholding his status at the court; rather, he is doing everything that will help him rescue and return to his love. This dependence on women for help shows us Lancelot's acknowledgment of the importance and power of women. This is contrary to the ideals of court, where women are merely objects of the knights' protection. Yet Lancelot does not have to defend his honor in front of other knights, which means he can freely accept help from women. This results in his rescue when other knights cannot get to him, and in turn serves as one of the most important sources of his power. Relationship with Guinevere It is difficult to speak of Lancelot without mentioning his relationship with Guinevere, which first appears in The Knight of the Cart by Chrétien de Troyes, since it defines Lancelot as a character. The relationship between Lancelot and Guinevere is morally questionable and highly unusual. First of all, it is an illicit love affair, as Guinevere is legally wedded to King Arthur, Lancelot's lord. This is both sinful, since Christianity prohibits sleeping with a married woman, and a violation of chivalric code, since Lancelot has sworn allegiance to his lord King Arthur. Yet Chrétien sympathizes with Lancelot and writes, “if ever anyone loved / more truly than Pyramus / It was [Lancelot]” (3810-3812). Furthermore, the reader can't help but notice that the relationship consists of a very unusual, complete submission on Lancelot's part. A few lines earlier, Chrétien states, Lovers are obedient men, Cheerfully willing to do Whatever the beloved, who holds Their entire heart, desires. (3805-3808) When Lancelot is forced to sleep with a damsel whom he encounters on his adventures, he is not even tempted to be disloyal to Guinevere: ...his heart Had been captured by another woman, And even a beautiful face Cannot appeal to everyone. The only heart our knight Owned was no longer his To command, having already Been given away; (Chrétien 1229-1236) Lancelot's giving away the control of his heart to Guinevere shows his complete submission to his lover. The important implication here is that Lancelot's allegiance to the court is secondary to his love for Guinevere. Another instance that shows Guinevere's control over Lancelot's actions is the tournament episode. When Guinevere commands Lancelot to perform poorly, he willingly submits, even if it brings him shame and humiliation among other knights. Furthermore, in the middle of the battle, Guinevere's messenger tells Lancelot: Do your fighting with your face Turned to this tower, so you'll see her Better! (3708-3710) Upon receiving this ridiculous command, Lancelot does exactly as she commands him, fighting his enemy with his head turned to the tower. Here, he is risking both his reputation and his life in his submission to Guinevere, which once again emphasizes the importance he places on his relationship with his lover. This obsessive and unusual relationship with Guinevere causes Lancelot to experience symptoms of love-sickness. On his quest for Guinevere in The Knight of the Cart, Lancelot encounters the sentinel who forbids the crossing of the ford. However, Chrétien states that “all our knight heard was his own / thoughts” (758759). The sentinel's warnings do not register in Lancelot at all, since his mind is disconnected from reality and obsessed with thoughts of Guinevere. Eventually Lancelot is thrown off his horse by the angry sentinel and only then does he awaken out of his daydream. This shows that Lancelot's obsession with Guinevere makes him tune out from reality, which often endangers him. Furthermore, when a damsel shows Lancelot Guinevere's comb with her hair on it, Lancelot ...seemed Unconscious, lost to his senses, And very nearly was, As close as a man can come, For his heart was filled with such sadness That for a long moment the blood In his face disappeared, and his mouth Could not move. (1436-43) A sight of Guinevere’s hair physically paralyzes Lancelot for a moment, which is another sign of infirmity caused by love-sickness. In Malory's text, Lancelot goes insane when he finds out that he was tricked into sleeping with Elaine. He “leap[s] out at a bay-window into a garden, and there with thorns he [is] all to-scratched of his visage and his body; and so he [runs] forth he [knows] not whither, and [is] as wild-wood as ever was man” (84). Once again, the deception doesn't cause Lancelot's madness, but rather triggers his love-sickness to surface in a form of madness. Lancelot's obsessive love for Guinevere is the primary cause of his condition. However, alongside the psycho-somatic impairments, Lancelot's lovesickness also results in his enormous, superhuman powers. In Chrétien, Lancelot crosses the Sword Bridge, which is a nearly impossible task. The people advise him against crossing the bridge: This bridge is wickedly built, Evilly put together. Change your mind now --Or else you'll lose the chance. A man must think both long And hard before he acts. Suppose you get across--But it isn't going to happen: No one can hold back the wind And stop it from blowing, or forbid Birds to open their beaks And sing, and keep them silent, Or climb into a mother's Womb and be born again (3048-3062) Yet Lancelot does the impossible and crosses the bridge because he can't let anything stop him from getting to Guinevere. This task reveals his superhuman prowess, caused by his love-sickness and devotion to Guinevere. Furthermore, these lines imply that Lancelot's prowess is godlike, since he accomplishes something as impossible as being reborn, which equates Lancelot's feat to the awakening of Jesus Christ (Cohen, Medieval Identity Machines 107). Another comparison of Lancelot to Jesus Christ is made earlier in the poem when Lancelot accomplishes another impossible task by lifting the stone from the tomb. The monk explains that “Seven strapping men / Would be needed to open this tomb” (Chrétien 1897-1898). Yet Lancelot ...took hold Of the huge stone which he lifted As if it were light as a feather, Though ten men heaving As hard as they could couldn't do it. (1916-1919) Once again, Lancelot's strength here is said to exceed that of seven or ten men. In Malory, Lancelot is constantly referred to as the “best knight” with no equal in power or skill, such as when Sir Bors tells Guinevere, “Alas! ... that ever Sir Lancelot or any of his blood ever saw you, for now have ye lost the best knight of our blood” (86). In The Death of King Arthur, Lancelot encounters Gawain’s supernatural powers in battle. Malory writes, “Then had Sir Gawain such a grace and gift that an holy man had given him, that every day in the year from undern till high noon, his might increased those three hours as much as thrice his strength” (Malory 198). Yet Lancelot is able to resist and defeat him, which proves that his strength goes beyond that of a mortal. Conflicting Identity In The Knight of the Cart, Lancelot's identity is obscured throughout the first half of the poem. Lancelot is very insistent on keeping his identity secret. It first becomes evident when the girl's attempts to find out his name evoke an angry response from Lancelot: Haven't I told you I come From King Arthur's court? In the name Of God Almighty, I swear I'll never tell you my name! (Chrétien 2009-2012) For a while, the audience and other characters only know him as “the knight of the cart,” which means that Lancelot's identity stems from the ignoble cart rather than his name (which signifies his nobility and prowess). As Jeffrey Cohen points out in Medieval Identity Machines, “the cart is described as a space wholly outside of chivalric identity” (93). By making a transition from his horse to the cart, Lancelot gives up his knightly identity for one of ...murderers, thieves, Those defeated in judicial Combat, robbers who roamed In the dark, and those who rode The highways... (Chrétien 328-332) There is a special significance in a knight giving up his horse, as Cohen once again explains, “a knight (chevalier) without a horse (cheval) is no knight at all” (93). It is very strange that the best knight of the Round Table would give up that identity so easily. It is also important to note that this switch wasn't an unintended outcome of the moment. Before the trip in the cart, Lancelot exhausts his horse and “The horse / He left behind him fell dead” (295-296). This, as Cohen points out, “suggests that Lancelot is pushing knightly identity to its extreme, to that limit at which it begins to discohere” (93). From these incidents, we can conclude that Lancelot either does not value his knightly identity, or that he is willing to sacrifice it for an identity more important to him. When Gawain offers Lancelot another horse to replace his dead one, Lancelot made no attempt to choose The better, or bigger, or faster, But simply mounted the one That happened to be closest, and galloped Away at once. (Chrétien 291-295) Here, he puts no effort into establishing his identity through a conventional image of a strong knight on a strong horse (as discussed earlier), since he is in a rush to get to Guinevere. From this, we can conclude that Lancelot wants to have the identity of Guinevere's lover; he rushes to rescue her in order to establish that identity. His knightly identity stems from his identity as Guinevere's lover, and more importantly, through Guinevere he becomes not merely “the knight of the Round Table,” but “the greatest knight of the Round Table.” With that in mind, it's no surprise that we first learn of the knight's identity from Guinevere, when she says, As long as I've known him, this knight's name Has been Lancelot of the Lake (3665-66) From there on, the Knight of the Cart becomes Lancelot, the greatest knight of the Round Table, who performs exceptionally well at the tournament (at Guinevere's command) and rescues the queen and the knights from Méléagant's captivity. Lancelot's knightly identity is not restored by the Round Table but rather by Guinevere. This shows us that Lancelot's primary identity is that of a Guinevere's lover, without which his identity as the “best knight” would be nonexistent. In Malory’s Lancelot and Elaine, after Lancelot revives from his madness, he masks his identity as well. When Lancelot goes off to live in the Castle of Blyaunt, Malory writes that “there he was called none otherwise but Le Chevalier Mafete, ‘the knight that hath trespassed’” (95). However, here his identity is “restored” by a fellow knight, Sir Perceval, who convinces Lancelot to reveal his name. Lancelot says “what have I done to fight with you which are the knight of the Round Table” (97), which shows Lancelot's guilt about abandoning the Round Table, disconnecting his identity from it, and going so far as to fight another fellow knight. Here, he even more dramatically transforms his identity, since even in Chrétien Lancelot acknowledges that he “come[s] / From King Arthur's court” (2009-2010), even though he doesn't reveal his name. Furthermore, Lancelot's madness in Malory shows that his identity is even more dependent on Guinevere than in Chrétien; he absolutely cannot accept to be Elaine's lover. When he is tricked into it, he transforms from Lancelot “the best knight” into Lancelot “the madman” and “the knight that hath trespassed.” The Court's Dependence on Lancelot Despite his isolation and introversion, Lancelot plays a critical role in the success of The Round Table. The court's existence is absolutely dependent on Lancelot standing up to challenges, affirming The Round Table's prowess at the tournaments, and rescuing the queen from captivity. In Chrétien, both Sir Kay and Sir Gawain are unable to escape captivity without the help of Lancelot. In Malory's The Poisoned Apple, when the queen is accused of trying to poison Gawain, Lancelot isn't at the court. At that moment, Arthur realizes how much the court relies on Lancelot: “That me repenteth,” said King Arthur, “for an he were here he would soon stint this strife.” (119) Arthur realizes that when someone accused the queen in the past, Lancelot would vindicate her through his enormous prowess in battle. Yet in The Poisoned Apple episode, the queen is almost burned because of Lancelot's absence, and only saved because Lancelot shows up toward the end of the story and rescues her. In The Death of King Arthur, however, Lancelot is unable to save the court from its downfall. Still, unlike other knights, Lancelot actively tries to preserve The Round Table. Lancelot is sure that with his power he is able to defeat Sir Gawain and bring victory to his side of the court, but he persists in trying to reconcile with Gawain. Lancelot says, If it may please the king's good grace and you, my lord Sir Gawain: I shall first begin at Sandwich, and there I shall go in my shirt, bare-foot; and at every ten miles' end I shall found and gar make an house of religion, of what order that you will assign me, with an holy convent, to sing and read day and night in especial for Sir Gareth and Sir Gaheris (187). This shows that despite all the tension, Lancelot is able to stay level-headed and make informed decisions regarding what's best for the court. He is singlehandedly trying to save the court from its downfall. Gawain, on the other hand, gives in to emotion over his two killed brothers and actively brings about its downfall. Arthur plays a passive role, and despite his desire to reconcile with Lancelot, he fails to act in order to save the court. In the end, Lancelot cannot save the court, because the relationship between Lancelot and Guinevere on which the court rests becomes the reason for the conflict. Chrétien's poem does not deal with consequences of this contradiction because it offers no ending to the story of Arthur. Malory, however, finishes the story; yet the only possible resolution of this paradoxical nature of the court, which relies for its success and reputation on an illicit love affair between a knight and the queen, is the downfall of the court. Lancelot is only able to save the court from ruin when his disloyalty to Arthur does not become the core of the conflict. The character of Lancelot, from his creation in the twelfth century, brings a heartbreaking paradox to the court of King Arthur. The court's existence rests upon the knight who defies the core values of The Round Table. Thus, the court itself rests upon values contrary to those it upholds. As a result, the only way to ensure the continuity of the court is to ignore this contradiction and allow Lancelot's devotion to the queen run its course. Whenever one of these aspects is challenged, the court is put at a high risk of disintegration. Bibliography Burns, E. Jane. "Refashioning Courtly Love: Lancelot as Ladies' Man or Lady/Man?" Constructing Medieval Sexuality. Ed. Peggy McCracken, Karma Lochrie, and James A. Schultz. Minneapolis: U of Minn P, 1997. 111-34. Chrétien de Troyes. Lancelot, The Knight of the Cart. Trans. Burton Raffael. New Haven: Yale UP, 1997. Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. Becoming Male in the Middle Ages. New York: Garland, 1997. Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. Medieval Identity Machines. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. Hanning, Robert. The Individual in Twelfth-Century Romance. New Haven: Yale UP, 1977. Harper, Ryan. “Gawain: Texts, Images, Basic Information” The Camelot Project at the University of Rochester. Web. 30 Dec. 2009. <http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/gawmenu.htm>. Malory, Thomas. King Arthur and his Knights: Selected Tales. Ed. Eugene Vinaver. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1975. Wack, Mary F. Lovesickness in the Middle Ages. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Press, 1990. Walters, Lori. Lancelot and Guinevere: a Casebook. New York: Garland, 1996.