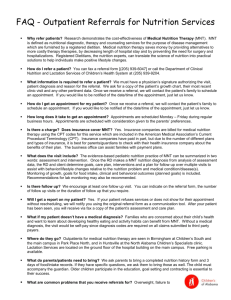

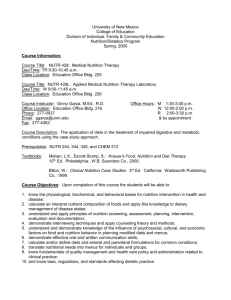

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics National Coverage

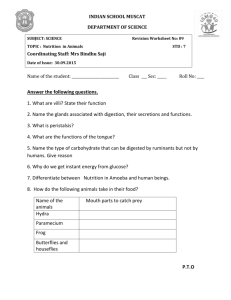

advertisement