Economics 6 World Vision A Hungry World: Understanding the

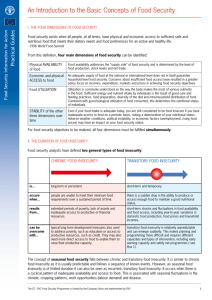

advertisement