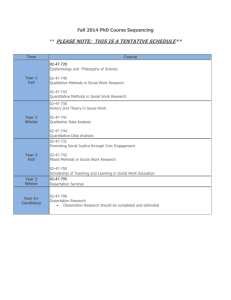

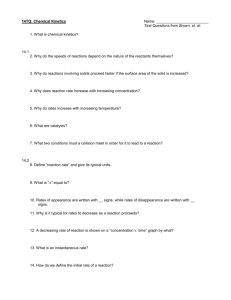

drnevich dissertation

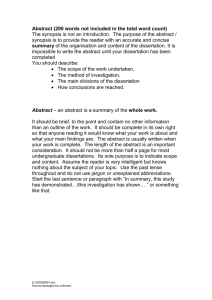

advertisement