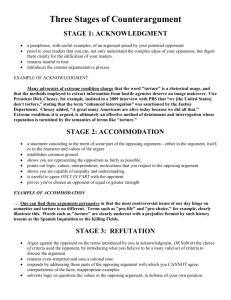

Extraordinary Rendition, Torture, and

advertisement