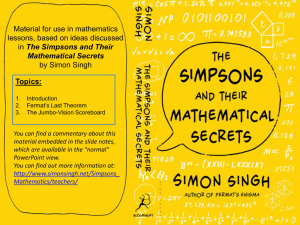

in The Simpsons

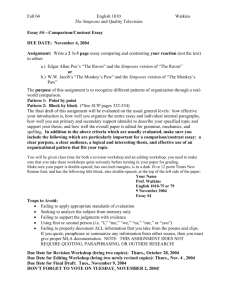

advertisement