I'm not in the mood for a party tonight

advertisement

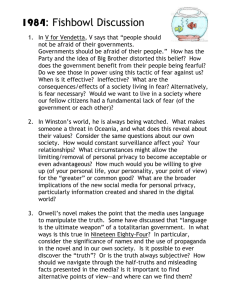

Hugvísindasvið “I‘m not in the mood for a party tonight” The Orwellian roots of the Pinteresque Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Magnús Teitsson Maí 2011 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska “I‘m not in the mood for a party tonight” The Orwellian roots of the Pinteresque Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Magnús Teitsson Kt.: 190472-5319 Leiðbeinandi: Martin Regal Maí 2011 Teitsson 1 Abstract This essay discusses the substantial and hitherto largely unacknowledged debt that Harold Pinter’s plays owe to George Orwell’s grand statement and last novel, Nineteen EightyFour. Attributes and themes of Pinter’s plays which have been widely acknowledged by critics as so typical of his works that the adjective “Pinteresque” has been ascribed to them, such as the volatility of the past, enclosed spaces, intrusion and the power struggles inherent in language. “By investigating close parallels between Pinter’s plays on one hand, particularly The Birthday Party, his first major play, as well as the “memory play” Old Times, and Nineteen Eighty-Four on the other, Pinteresque features will be shown to be also Orwellian in nature. Pinter repeatedly brought the Orwellian vision of a major political struggle to the stage cloaked as a microcosmic battle of wills, much as Orwell did himself in the final third of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Starting with a discussion of the background of The Birthday Party and moving on to separate chapters about the past, enclosed spaces, and language, the politically Orwellian aspect of Pinter’s oeuvre, generally believed to have been of little weight until his overtly political plays in the 1980s and his increasing political activism, will thus be shown to be of vital importance from his earliest works onwards. Teitsson 2 Table of contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................3 The Birthday Party in a Political Context ...........................................................................5 The Mutability of the Past ................................................................................................ 13 Enclosed Space and Intrusion ........................................................................................... 22 Language as a Weapon ..................................................................................................... 29 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... 35 Works cited ...................................................................................................................... 36 Teitsson 3 Introduction Pinter’s style as a playwright has given rise to a particular adjective, “Pinteresque”. According to the second edition of The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), published in 1989, this means “Of, pertaining to, or characteristic of the British playwright Harold Pinter (b. 1930) or his works” (Simpson). This definition is of little assistance when it comes to explaining what the word actually means, so it seems necessary to look elsewhere below to clarify the matter. However, the OED does indicate that the term was first used in The Times on 28 September 1960, a mere three years after the first production of The Room. This suggests that as early as at the turn of the 1960s, Pinter’s stylistic image was well formed among British theatre critics at least. Pinter’s mainstream reputation reached its apex in 2005, when the Swedish Academy announced that he was to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. In a biobibliography, the Academy summarises Pinter’s legacy as follows: Pinter restored theatre to its basic elements: an enclosed space and unpredictable dialogue, where people are at the mercy of each other and pretence crumbles. With a minimum of plot, drama emerges from the power struggle and hide-and-seek of interlocution. Pinter's drama was first perceived as a variation of absurd theatre, but has later more aptly been characterised as ‘comedy of menace’, a genre where the writer allows us to eavesdrop on the play of domination and submission hidden in the most mundane of conversations. In a typical Pinter play, we meet people defending themselves against intrusion or their own impulses by entrenching themselves in a reduced and controlled existence. Another principal theme is the volatility and elusiveness of the past. (Svenska Akademien) Teitsson 4 The Nobel Prize, which Pinter could not accept in person in Stockholm due to illness, is generally regarded as one of the highest honours that an author can attain, if not the highest, and thus the Academy’s outline of Pinter’s style serves as a good starting point to analyze and criticize the generally accepted meaning of “Pinteresque”. After the initial chapter, “The Birthday Party in a Political Context”, strong elements of the Academy’s summary will be shown to have thematic and at times stylistic roots in Nineteen EightyFour. The thematic chapters “The Mutability of the Past”, “Enclosed Space and Intrusion” and “Language as a Weapon” focus on parallels between Pinter’s work and Nineteen Eighty-Four to show how the two are related. Although these three major themes are dealt with in separate chapters, they do overlap at times and will therefore show up at different points in the essay. Teitsson 5 The Birthday Party in a Political Context Pinter’s early visions of local totalitarianism spoke directly to a constituency that, like himself, was steeped in Orwell and Kafka... (Raby 32. John Stokes: “Pinter and the 1950s”) After having been evacuated to the countryside as a child during World War II, Harold Pinter became an adult in the war-ravaged post-war London that served as the visual stage of Nineteen Eighty-Four, where it is described as “...bombed sites where the plaster dust swirled in the air and the willowherb straggled over the heaps of rubble...” (Orwell 5). As Francesca Coppa states in “Comedy and politics in Pinter’s early plays”, “The plotline of The Birthday Party was being played out as the most utter realism throughout Europe during Pinter’s childhood and teens” (Raby 51). Although Hitler had been defeated at great cost, Stalin’s Soviet Union was an alarming presence, closing road and rail access to West Berlin in June 1948 in an attempt to isolate and ultimately expel the Americans, the French and the British from the former German capital. Amidst the fear of a nuclear confrontation between the superpowers over the struggle for Berlin, the spectre of fascism had by no means been defeated in England, let alone Europe. While Sir Oswald Mosley had in the years before the war fronted the British Union of Fascists, in 1948 he formed the rightwing Union Movement (with the same flag as the BUF, closely related in design to the flag of Hitler’s Third Reich), intending to expand from British nationalism to a pan-European racist ideology. With the threat of totalitarianism still present, ideological struggles still manifested themselves in violence. In London, which had seen a steady influx of immigrants, not least Jewish, since the beginning of the century, Mosley’s followers (the likeliest models for the “gangs of youths in shirts all the same colour” (Orwell 186) referenced in Nineteen Eighty-Four), clashed with left-wing militants. Pinter recalled the Teitsson 6 atmosphere of the late 1940s in an interview with Lawrence M. Bensky in The Paris Review in 1966: Everyone encounters violence in some way or other. It so happens did encounter it in quite an extreme form after the war, in the East End, when the fascists were coming back to life in England. I got into quite a few fights down there. (Smith 61) When Pinter was called up for military service upon turning eighteen in October 1948, he immediately registered as a conscientious objector, “a particularly courageous act” for its time (Billington 21). Thus, ten years before The Birthday Party was staged for the first time, Harold Pinter declared himself an opponent of violence and oppression, finding himself in conflict with the authorities and having to appear before two military tribunals and two civic trials. The Birthday Party was first produced for the stage in 1958, nine years after the publication of the grim dystopia of Nineteen Eighty-Four. In Pinter’s play, whose title may well be at least a partial pun on the all-seeing and ever-present “Party” of Orwell’s bleak novel (supported by the political message of Pinter’s later work Party Time), the phlegmatic Stanley Webber has fled his tormentors in post-war London, the setting for Winston Smith’s ordeals in Nineteen Eighty-Four. (Both characters are in their late thirties and share the same initials, although this may be purely coincidental.) Stanley leads a tranquil existence in a seaside boarding house, alongside the doting and maternal landlady Meg, who pampers and teases him to the point of incest, her nearly translucent husband Petey, and a flippant young girl by the name of Lulu. Stanley’s world is brutally gatecrashed by two sinister characters, a Jew named Goldberg (“Gold-something”, in Meg’s words) and an Irishman named McCann “with a green stain on his chest” (Various Voices 149). It is probably not a coincidence that apart from Big Brother, the two most notable authority figures in Nineteen Eighty-Four are the similarly tagged Jew Emmanuel Goldstein, the (probably fictional) figurehead of the opposition, based on the outlaw Teitsson 7 Bolshevik revolution leader Leon Trotsky, and the Irishman O’Brien, who exposes Smith as an enemy of the state and then brainwashes him. Goldberg and McCann set about systematically breaking Stanley down by a seemingly endless barrage of questions and insults, which he initially attempts to stand up to but is ultimately powerless to resist. There is, however, a difference between O’Brien on one hand and Goldberg and McCann on the other in that “Goldberg and McCann are themselves victims. They represent not only the West’s most autocratic religions, but its two most persecuted races” (Billington 80). As man brutalizes man in Pinter, even the oppressors are victims, in true dystopian fashion. To put The Birthday Party into a slightly wider literary perspective, the plight of Stanley Webber echoes that of Josef K. in Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial (Der Process), which was first published in 1925, a year after death of the author, and which Pinter first read at seventeen and later turned into a screenplay for an eponymous 1993 film. Both works feature an everyman engulfed by forces of authority whose motives are left unexplained, ending in the protagonist’s execution in the case of Kafka’s novel. The ending of Nineteen Eighty-Four is near-identical to that of The Trial, giving a glimpse of the central character’s final thoughts at the moment of his execution. In turn, Nineteen EightyFour is generally acknowledged to have been inspired by Yevgeny Zamiatin’s 1923 novel We and Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel Brave New World, both of which deal with futuristic totalitarian regimes. Upon its debut in London in May 1958, The Birthday Party received mostly poor reviews. While The Cambridge Review described Pinter’s “effects” as being “strictly for kicks” and claimed the play to be “nihilistic” (Cambridge Review), W.A. Darlington of the Daily Telegraph declared that since the author hadn’t described what the play was about, neither could he. Harold Hobson of The Sunday Times was a lone voice of praise: Teitsson 8 The fact that no one can say precisely what it is about, or give the address from which the intruding Goldberg and McCann come, or say precisely why it is that Stanley is so frightened of them is, of course, one of its greatest merits. (Hobson) Given the fact that various critics doubted whether Pinter’s early plays meant anything at all, his political commitment as a playwright was in question from the very start of his career. Esslin, who counts Pinter among “the younger generation of playwrights who followed in the footsteps of the pioneers of the Theatre of the Absurd” (The Theatre of the Absurd, 234), notes that “Pinter has, at times, been accused of being totally a-political” but points out that his plays contain “the basic political problems: the use and abuse of power, the fight for living-space, cruelty, terror” (Pinter: A Study of His Plays, 32). While speculating on elements of popular culture of the time found in The Birthday Party, Billington however states (77) that “[t]he power of the play ... resides precisely in the way Pinter takes stock elements of popular drama and invests them with political resonance” and that “[i]t is a play about the need to resist”, which brings us back to Pinter as a conscientious objector and political free-thinker. With the combination of his already established personal political agenda and what considerable theatrical tools he had at his disposal at the time, Pinter fashioned The Birthday Party as a political statement about the dangers of oppression. In the collection of writings Various Voices: Prose, Poetry, Politics 1948-2005, whose title alone suggests that politics were a major theme of Pinter’s work throughout his career. Pinter defends his supposed failure to offer an explicit explanation of meaning with a few sentences that might have soothed W.A. Darlington of the Daily Telegraph: Meaning begins in the words, in the action, continues in your head and ends nowhere. There is no end to meaning. Meaning which is resolved, parcelled, labelled and ready for export is dead, impertinent – and meaningless. (Various Voices 13) Teitsson 9 Through his correspondence, however, Pinter is himself on record indicating what his intentions were with The Birthday Party. In a letter to the director, Peter Wood, on 30 March 1958, he summarizes the play: We’ve agreed: the hierarchy, the Establishment, the arbiters, the socioreligious monsters arrive to affect censure and alteration upon a member of the club who has discarded responsibility (that word again) towards himself and others. … he fights for his life. It doesn’t last long, this fight. His core being under a quagmire of delusion, his mind a tenuous fuse box, he collapses under the weight of their accusation – an accusation compounded of the shit-stained strictures of centuries of ‘tradition’. (Billington 78) The parallel with Nineteen Eighty-Four is evident through Pinter’s description; in both works, a man who puts up a short and futile resistance by fleeing from the conformity of a dominating authority is apprehended, brainwashed, and crushed. In October 1989, his political stance by then well documented and his more recent plays rightly seen as direct political statements, Pinter acknowledged that in the “early days” he had been “a political playwright of a kind” (Gussow 82), and in September 1993, he was even more blunt when discussing the underlying nature of his early plays: [...] I knew perfectly well that The Birthday Party and The Dumb Waiter, in my understanding then, were to do with states of affairs which could certainly be termed political, without any question [...] And Goldberg and McCann, I knew who they were and what they were up to. (Gussow 113) The political motive being admitted, the notion of the early Pinter as a strictly “absurdist” playwright with no underlying message or ethical agenda can thus be safely put to rest. Although the nature of Goldberg and McCann’s breakdown of Stanley in The Birthday Party is more verbal than physical, there is actual violence on a small scale, such Teitsson 10 as crushing Stanley’s glasses and gripping his hand too tightly. In Various Voices, Pinter more explicitly reveals the underlying threat of violence by explaining that in view of what happened to Stanley, “We all have to be very careful. The boot is itching to squash and very efficient” (Various Voices 13). This imagery borders on plagiarism when seen next to O’Brien’s description of the future as related to Winston Smith: Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever. (Orwell 307) One reason for the relatively low level of violence in The Birthday Party may be the requirements of the theatre at the time, in which hints of brutality were likely a more economical way of conveying oppression than flat out physical aggression. Another explanation may be that the groundwork had been laid in Nineteen Eighty-Four, where actual violence is the basis for intimidation. After Winston Smith has gone through a period of regular beatings at the Ministry of Love, physical torture becomes more of a threat to him, “a horror to which he could be sent back at any moment when his answers were unsatisfactory” (Orwell 277). Instead, less extreme physical hardships, at the hands of Party intellectuals rather than brutal guards, are utilized “to humiliate him and destroy his power of arguing and reasoning” (Orwell 277). When the Party questioners have inflicted their mental torture upon Smith, including switching to pleas for him to confess for the sake of loyalty to the Party, his will to resist is exhausted: In the end the nagging voices broke him down more completely than the boots and fists of the guards. He became simply a mouth that uttered, a hand that signed, whatever was demanded of him. (Orwell 278) At the end of The Birthday Party, Stanley has been broken down by mental torture and the ever-present threat of violence in a manner comparable to the fate of Winston Smith. Once Smith has been subjected to enough physical torture, the mere hint of violence Teitsson 11 is enough to elicit his capitulation at any time. This is where Orwell signs off and Pinter picks up his mantle of politically themed warnings, using an uneven psychological match as a recurring theme of his characters’ interaction. Not until the 1980’s, however, did Pinter’s political position become common knowledge, as he became a campaigner for human rights worldwide through PEN and Amnesty International. This breakthrough into overt activism coincided with a clearer approach to political issues in Pinter’s works than in his early plays which contained the idea of a political stance cloaked in a more abstract approach. The Hothouse, which Pinter had written in 1958, after The Birthday Party, was finally staged in 1980 under the direction of the author himself, beginning a political trend that was to dominate Pinter’s plays throughout the decade. As he said in September 1993, “[t]he Hothouse couldn’t be more political” (Gussow 113). As an unsettling and disorientating examination of power struggles within a mental asylum, The Hothouse was a perfect bridge between the opaque politics of early Pinter and the clear statements against oppression that were to follow, including Mountain Language, which is discussed in later in this essay in the chapter Language as a weapon. In One for the Road, which opened in London in spring 1984, by coincidence or not, Pinter revisited the theme of interrogation, this time in a setting almost identical to the final chapters of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Esslin states: “these four short scenes between an interrogator and his victims are clearly a direct continuation of Pinter’s preoccupation with ‘man manipulating man’ that extends from The Room and The Dumb Waiter via The Caretaker and The Homecoming to the sinister pair of servants in No Man’s Land.” (Pinter: A Study of His Plays, 207) It is odd, or amazing even, that Esslin leaves The Birthday Party out of this rather long list, but the explanation may be that he finds it to be such an obvious precursor that it’s more instructive to mention plays that have a common thematic background without being overtly similar in setting. Teitsson 12 The Orwellian/Pinteresque interrogation/torture scene was finally condensed in The New World Order, a short play first staged in 1991, whose title makes it clear that totalitarianism is the issue and the motivator for the actions of the characters onstage. As two men stand over a blindfolded third man sitting in a chair, clearly intending to hurt him and his unseen wife, they both verbally abuse him and discuss among themselves the importance of language. Not only do they justify themselves by claiming to be “keeping the world clean for democracy”, but the final words imply that in a short while, the man in the chair will be thankful to them. The analogy to the breaking down of Winston Smith and his conversion to brainwashed gratitude in death is close at hand, and so the political violence that was first hinted at in The Birthday Party is finally imminent. Teitsson 13 The Mutability of the Past ‘Who controls the past,’ ran the Party slogan, ‘controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.’ (Orwell 40) Although the past and the perennial battle to revise it is a recurrent motif in Pinter’s work, Byczkowska-Page contends that very few critics have grasped the importance of the past in Pinter’s earlier plays (19). According to Gussow, however, “A Pinter plot is created not by intricate intrigue but by the manipulations of past and present” (Alexander 1). Furthermore, time in Pinter is not only malleable but seemingly fluctuates of its own accord: “Time, in Pinter’s plays, progresses subjectively and at disturbingly varying rates.” (Regal 3) Chronological disruptions present themselves by way of the basic theatrical mechanisms of sound (or lack thereof) and motion, stating that Pinter is “deeply engaged in a temporal dilemma manifested as much by silence and movement as by language” (Regal 4). The importance that the past holds throughout Pinter’s output has led critics (Dukore, Esslin and others) to classifying certain plays of his, notably Landscape, Silence and Old Times, as “memory plays”. In these plays, the past is not only an unclear factor but a focal point where all underlying tensions are acted out. Specifically in The Birthday Party, the mutability of the past hands any would-be aggressors a potent weapon of psychological tyranny. The twisting of time is an integral component of Goldberg and McCann’s brainwashing of Stanley: A large degree of Goldberg’s power over Stanley resides in his ability to distort sequence. In the only instance of a poem which specifically relates to one of his plays, Pinter says that the two men (Goldberg and McCann) ‘imposed upon the room / a dislocation and doom’. This ‘dislocation’, clearly evident in the interrogation scenes, is manifested by breaking down Teitsson 14 Stanley’s ability to maintain any sense of order in his mind, not least a temporal order. (Regal 22) The effect of Goldberg’s tactics of obfuscation upon Stanley is to throw him back into a more childlike state as a means of self-defence, as described by Pinter himself in the following way: Stanley behaves strangely. Why? Because his alteration-diminution has set in, he is rendered offcock (not off cock), he has lost any adult comprehension and reverts to a childhood malice and mischief, as his first shelter. This is the beginning of his change, his fall. (Various Voices 15) Revision and disorientation relating to the past are not, however, just blunt instruments of oppression in The Birthday Party, but a ubiquitous element of the dramatic structure. Even the most innocent and least calculating people, the working-class “proles” such as Meg and Petey, have a tendency to try to re-order the facts. The past which is under revision may be as recent as the content of a newspaper article, as in the first scene when Meg follows up Petey’s proclamation that someone has had a baby by asking about its sex in characteristically monosyllabic style: MEG. What is it? PETEY (studying the paper). Er–a girl. MEG. Not a boy? PETEY. No. MEG. Oh, what a shame. I’d be sorry. I’d much rather have a little boy. (Pinter 1.5) This is a case of inviting an alternate answer, as if that’s as real an option as accepting the previous factual statement. Frivolous though it may seem, this farcical line of enquiry, presented very early in the play, indicates that simple statements of what is factually correct will be questioned. This questioning will not be conducted in a spirit of Teitsson 15 critical thinking, but by way of manipulation. Meg’s stake in the matter of the gender of the child of “someone” in the paper is very trivial, but this only lends a sordid weight to her repeated attempts to elicit a different presentation of reality from Pete than that which he has plainly stated. Even such a fundamental and, one would assume, verifiable issue such as that of the date of Stanley’s birthday is clouded by discrepancies and arguments. As Meg tells Goldberg and then Stanley himself at the end of Act One that it is the latter’s birthday, Stanley plainly states that it is not his birthday, but nevertheless accepts her gift of a boy’s drum. As he then meets McCann for the first time (in the play, at least) at the beginning of Act Two, Stanley then answers in the affirmative when McCann inquires if he’s going out on his birthday. The invention of the past in The Birthday Party can take the form of elaborate stories, such as Stanley’s tale of his career as a pianist, which spins off from his ludicrous claim that he is considering a job offer in Berlin, to be followed by a world tour. The speed with which Stanley builds his fables is further shown in the way he instantly revises his claim of having played all over the world and settles for having played all over the country. His story is psychologically revealing in that even when the original intention can only be to portray himself as a successful pianist, bitterness seeps through. At the end of his monologue, Stanley cannot stop himself from complaining sulkily about having been summoned to a concert in a hall that turned out to be boarded up, which is the one component of his account that is likely to be true. Stanley’s weakness and defensiveness is in this way portrayed through his own vision of the past, which was ironically meant to boost his image in the eyes of himself as well as the other characters. Goldberg’s numerous narratives of the past, on the other hand, are highly positive and have the added significance of containing a high density of references to time. (McCann’s rather less cerebral approach involves him tearing up a newspaper, physically Teitsson 16 destroying an account of the past in a habitual manner.) As Goldberg speaks of times gone by in glowing terms, he mentions an uncle named Barney who used to take him to the seaside, “regular as clockwork” (Pinter 1.21). This commanding phrase of chronological precision strikes a marked contrast to the shifting insecurity of Stanley’s recollections and establishes a tone of authority which Goldberg goes on to utilize when attacking Stanley’s self-image. Once he has established power over the past, Goldberg is then free to indulge in a number of discrepancies. The Fridays of Goldberg’s past life seem to have been filled with an inordinate amount of regular occurrences (Regal 22) but of more import are the inconsistencies of Goldberg’s name, as he goes from “Nat” to “Simey”. Just as the Party in Nineteen Eighty-Four is in a position to tell the citizens of Oceania that two plus two is five and make them accept it, Goldberg’s position of strength enables him to invent fables at will without serious challenges from the other characters. As he moves to a more brutal attack on Stanley, the gilded reminiscences of Goldberg’s youth are left unassailed, allowing him and McCann to abduct Stanley under a pretext of finding him “special treatment” (Pinter 1.79), a thinly veiled euphemism for torture and further brainwashing. The Birthday Party concludes with Meg closing her eyes to Stanley’s removal by asking Petey if he’s still in bed, then drawing a wishful picture of the previous occurrences, saying it was “a lovely party” with “dancing and singing”, and that she was “the belle of the ball”: MEG. Oh, it’s true. I was. Pause. I know I was. (Pinter 1.81) As Queen Gertrude says in Hamlet, “The lady doth protest too much” (Shakespeare 73). This trademark of Pinter’s, a character making a claim seemingly to convince themselves of its truthfulness (with a characteristic pause for added emphasis), but coming off as merely thinking wishfully instead (if not deceitfully re-organizing the past), trying to Teitsson 17 settle on an acceptable or even glorious version of an unpalatable past, has the final effect of merely undermining all claims of credibility on behalf of the character. Meg seems oblivious to how absurd her statements are when examined and contrasted with the actual situation, much like Winnie in Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days, who proclaims her delight at “Another heavenly day” while she is half buried in the ground (Beckett 135). The Orwellian twist is the implication that the one person who was capable of challenging the glamourized portrayal of past events, in this case Stanley, has been “vaporized”, to use the term from Nineteen Eighty-Four. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the past holds no less significance than in any of Pinter’s “memory plays”, the Pinteresque undertaking of actually rewriting the past even being the main character’s job. At his workplace, the Records Department of the Ministry of Truth, Winston Smith’s task is to “rectify”, that is to falsify, records of the past, even making up entire biographies of fictional persons to present a picture of reality consistent with the Party’s current utterances and viewpoints. The past has become so clouded through such constant and thorough revision that the work of Winston Smith does not even amount to forgery; he reflects that it is “merely the substitution of one piece of nonsense for another” (Orwell 48). Smith does not merely touch upon the past professionally; all the things he is fascinated by are old, as if they in themselves contained some truth about the past that is unreachable by normal means. The objects may be ordinary, such as books or pens, but as long as they are old they give him comfort by offering insights into bygone days. Even an old nursery rhyme like “Oranges and lemons”, which relates the names of a few London churches, holds significance as a gateway to the truth of the past. Smith’s rebellion has strong themes of time and the past; his first concrete subversive act is to write down the date although he is not even sure what year it is (Orwell 9). Teitsson 18 Neither is Smith alone in recognizing the politically charged power of the past. The very Pinteresque phrase “the mutability of the past” appears twice in Nineteen Eighty-Four, in the latter instance even being revealed to be “the central tenet of Ingsoc”, that is to say English Socialism, the ideology of the Party (Orwell 243). Winston Smith realizes that the lack of a reliable past to relate to and use as a basis for one’s own self-image and values has a devastating effect upon one’s psyche: When there were no external records that you could refer to, even the outline of your own life lost its sharpness. You remembered huge events which had quite probably not happened, you remembered the detail of incidents without being able to recapture their atmosphere, and there were long blank periods to which you could assign nothing. (Orwell 37) Orwell’s temporal dislocation does not merely reach into the past from the present. Ghostly presences such as the condemned political criminals Jones, Aaronson and Rutherford, who are “corpses waiting to be sent back to the grave” (Orwell 87), further underline how the present is not one clearly defined entity, but rather a blurry point in a mesh of time which the ordinary individual strains to cope with, not unlike the previously mentioned description of time in Pinter’s plays as a force that can change and disorientate on its own. In the final third of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the mentally debilitating effects of the slipperiness of the past become clear as Winston Smith is subjected to mental reprogramming. O’Brien starts his attack on Smith’s mind by declaring that he is insane because his sense of the past is deficient: You are mentally deranged. You suffer from a defective memory. You are unable to remember real events, and you persuade yourself that you remember other events which never happened. Fortunately it is curable. (Orwell 282) Teitsson 19 As O’Brien goes on to destroy Smith’s grip on reality, the aggressor’s ability to control the present through the past is a constant theme throughout. O’Brien even informs Smith: “You will be annihilated in the past as well as in the future.” (Orwell 291) In this way, the past is the key to all power. In 1971, midway between the initial production of The Birthday Party and Pinter’s overtly political plays of the 1980s, Old Times was staged for the first time. As indicated by its title, the play is about the past, falling into the previously mentioned category of “memory plays”, this time with a more marked element of wistfulness than usual and even a hint of the ghostly or supernatural. As set up by Pinter, the past is a battleground between the three characters, Deeley and Kate, who are married, and Anna, Kate’s old friend who she has not met in twenty years but is expected to turn up that evening at Deeley and Kate’s house in the country. Time is ever-shifting in Old Times and factual remembrances are hard to come by. After Deeley details a reminiscence of how he took Kate to see a movie called Odd Man Out, Anna brazenly attempts to hijack the memory by claiming that she went, “almost alone” (Pinter 4.34), to see a movie by that name. To openly accuse Anna of making up the memory or claiming it as her own would indicate weakness on Deeley’s part by not playing according to the rules of the game, so he retaliates by mocking her in a not so subtle way, claiming that he is the world famous film director Orson Welles and recounting his work producing a film. The verbal and psychological punches fly in every possible direction during the course of the play. Deeley patronises Kate by asking her what month it is, thereby handing down a blatant challenge of chronological perception, and then praising Anna’s influence in that it forces Kate to think. In turn, Kate later on in the play tells him that he’s free to leave if he doesn’t like the two women’s conversation. Kate and Deeley twice engage in a duel of singing lyrics from old show tunes, once in each act. The songs are a signal that the Teitsson 20 past is being romanticized, but the motivational implications of serenades such as these, being meant to woo the listener into submission, has a bearing of their meaning within the play. As in the songs, there is a romantic/sexual agenda governing the behaviour of every single character in Old Times, which is a manifestation of the ubiquitous psychological tugof-war. The song selection might easily have included a ditty about the passing of time, which appears in Nineteen Eighty-Four as sung by a proletarian woman grown old prematurely by the rigours of manual labour and child-bearing: They sye that time ‘eals all things, They sye you can always forget; But the smiles an’ the tears across the years They twist my ‘eart-strings yet! (Orwell 250) Kate and Anna wrestle for editorial control of the visions of their shared past, with the theme of death dominant. In Act One, Anna seems to be the one who is trying to implicate the other woman with death, and in an instance of a shifting alliance, Deeley joins in with her in the attempt to classify his wife as dead: KATE. You talk of me as if I were dead. ANNA. No, no, you weren’t dead, you were so lively, so animated, you used to laugh DEELEY. Of course you did. I made you smile myself, didn’t I? walking along the street, holding hands. You smiled fit to bust. (Pinter 4.30) In Act Two, the tables are finally turned when Kate reprises the theme of death and proclaims to Anna: “I remember you dead.” (Pinter 4.67) Her recollection is so detailed and vivid that both Anna and Deeley submit to Kate’s picture of the past. The struggle is over, and since Kate has wrestled control of the past, she emerges as the champion in the game of wits that has been played. Teitsson 21 To discuss Pinter’s approach to the past in a general way, it is worth pointing out an instance from Old Times, in the middle of the battle between the three characters for the right to recreate the past, where Anna says: “There are some things one remembers even though they may never have happened. There are things I remember which may never have happened but as I recall them so they take place.” (Pinter 4.27-28) Pinter himself valued this line and later mused about the uncertainty over how things happened, according to Joan Bakewell (Billington 265), whom he had a long-standing affair with. The Orwellian revision of the past has here been brought to Pinter’s theatrical level and condensed in one individual who decrees that bygone times are under her subjective control. The final Pinteresque definition of the past, which would have fit in snugly with O’Brien’s lectures to Winston Smith on the malleability of the past, is the following phrase from the author of Old Times himself: The past is what you remember, imagine you remember, convince yourself you remember or pretend you remember. (Lowenthal 193) Teitsson 22 Enclosed Space and Intrusion I am dealing a great deal of the time with this image of two people in a room. ... What is going to happen to these two people in the room? Is someone going to open the door and come in? (Harold Pinter, Theatre of the Absurd 235) The themes of an enclosed space and (people defending themselves against) intrusion are closely connected in Pinter’s plays, and central to the idea that said plays contain scenarios which can be read as microcosmic theatrical manifestations of a larger political struggle. The Pinteresque character will typically take cover in a room, seeking to shield himself from unseen forces: “Outside the room is a threatening presence: the Other, an unknown with power to destroy ... we may boldly state that the room represents one’s identity, always a precarious possession in Pinter, that is, oneself as dasein or being-there.” (Dobrez 323) The matter of an enclosed space being guarded against an invasion by outside forces, with all the Fascist connotations of the word Lebensraum in the wake of World War II, takes on a multitude of forms in The Birthday Party. Before any of the dialogue begins, the stage directions indicate that “Meg’s voice comes through the kitchen hatch” (Pinter 1.3), similarly to the unseen voice “babbling away” (Orwell 4) from a telescreen very early in Nineteen Eighty-Four, followed by her face. She then disappears and reappears, and finally enters by the kitchen door. In the first instance of an unwelcome intrusion in the play, Meg then proceeds to badger her husband Petey, who is hiding behind a newspaper in classic fashion, by way of incessant questions about trivial things, as discussed later in this chapter. The level of harassment is mild in this opening section, but it is significant that territorial encroachment is a factor from the beginning of the play. Immediately following this initial sparring contest between the husband and wife, Meg moves onto the unseen Stanley, shouting at him from downstairs that she’ll come up Teitsson 23 to fetch him if he doesn’t come down, and then in fact barging in on him in his room. The degree of imposition has thus been raised by transferring it from the traditionally communal kitchen to the privacy of a room, which is Stanley’s only personal hiding place from the outside world. The tone for the connection between Stanley on one hand and Goldberg and McCann on the other is set later in Act One after Meg informs Stanley that she is expecting two gentlemen to stay for a couple of nights. He instantly becomes agitated and quizzes her about the proposed visit, then states that they will not be coming and repeatedly proclaiming the situation a “false alarm” (Pinter 1.15). The immediacy of Stanley’s anxiety and his phrasing indicate that he does in fact view the possibility of the two guests’ arrival alarming, which implies that the coming invasion will carry a weight far beyond any normal everyday encroachment by the essentially harmless Meg. Stanley’s panic echoes the end of the first chapter of Nineteen Eighty-Four, when Winston Smith is already terrified of an intrusion as a result of his diary and starts violently as there is a knock at the door (Orwell 22). A glimpse of physical encroachment on the part of the two visitors is then offered when McCann shakes Stanley’s hand and holds the grip during their initial meeting at the start of Act Two, following this hint of tangible domination by standing in his way. The theme of gradually building physical limitations is subtly presented by an unwelcome intrusion into a personal space, with Stanley first being unable to move his hand at will and then his body being obstructed. The physical encroachment upon Winston Smith is gradual like that upon Stanley Webber, although the former is subjected to more explicit physical confinement. From an initial state of Smith being watched constantly and having no free time of his own, Nineteen Eighty-Four moves through his arrest and the following days of sitting on a bench, banned from moving, to a state of torture where he is strapped down and finds it “impossible to move so much as a centimetre in any direction”. (Orwell 283) Teitsson 24 The climax of Goldberg and McCann’s annihilation of Stanley’s will is finally reached at the very end of Act Two, as they converge upon him, in a manner reminiscent of a fugitive’s arrest. This physical enclosure signals Stanley’s conclusive defeat in the battle for a space to live in, and the loss of his will to fight. He therefore puts up no further resistance in Act Three, which has an air of resignation analogous to the last chapter of Nineteen Eighty-Four when the central character is merely waiting to die. The most theatrically startling instance in Pinter’s oeuvre of an intrusion into a personal space occurs in act one of Old Times after Deeley and Kate have spoken freely for what amounts to ten pages of written text. Having previously stood still and unnoticed in dim light at the window, reminiscent of a turned-down and temporarily forgotten telescreen, Anna makes her entrance by turning from the window to drop seamlessly into the conversation: DEELEY. Anyway, none of this matters. Anna turns from the window, speaking, and moves down to them, eventually sitting on the second sofa. ANNA. Queuing all night, do you remember? my goodness, the Albert Hall, Covent Garden, what did we eat? to look back, half the night, to do things we loved, we were young then of course, but what stamina, and to work in the morning, and to a concert, or the opera, or the ballet, that night, you haven’t forgotten? (Pinter 4.13) The effect of Anna’s introduction is to turn the focus away from the amiable chat of a married couple about a third person, instead leading into a triangular struggle for control. With its multiple Pinteresque qualities (selective and shaping remembrance of the past as a force to hold power over people in the present, an intrusion into an enclosed space), the scene above has a precedent in a pivotal moment in Nineteen Eighty-Four. As Smith and Julia sit in their rented room and reminisce on the first day they made love, Winston’s Teitsson 25 thoughts drift to the “proles” all around the world and how they would keep reproducing and living their simple lives, leading him to hope that one day they might become politically aware. As Smith and Julia acknowledge their own fate, a third party shocks them with its presence by echoing their thoughts out loud: You were the dead; theirs was the future. But you could share in that future if you kept alive the mind as they kept alive the body, and passed on the secret doctrine that two plus two make four. ‘We are the dead,’ he said. ‘We are the dead,’ echoed Julia dutifully. ‘You are the dead,’ said an iron voice between them. (Orwell 252) This abrupt shock, which holds no less power than Anna’s entrance in terms of theatrical impact, brings a sudden shift of perception with the realization that Smith and Julia have been watched under surveillance from close range all along. At this turning point, it becomes clear that they are in fact doomed; the voice comes from behind a telescreen hidden behind a painting on the wall and in its wake the house is invaded by a team of armed troopers who arrest the lovers for thoughtcrime. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the intrusion signals the final phase of the story, in which all alliances become meaningless and all that matters is the power one person holds over another. In A Kind of Alaska, which is based on the neurologist dr. Oliver Sacks’s 1973 book Awakenings, Pinter presents a dramatized case study of Deborah, a woman who wakes up from a coma of thirty years believing she is still sixteen years old. Although the familiar theme of temporal dislocation is at the forefront of the play, enclosure is a vital component of Deborah’s psychological state, and one which she details eloquently. In a sense Pinter even takes his themes of confused time and confined space further than usual, as the main character goes from being imprisoned in her own mind to being wrong about the current time by nearly three decades. Rose, the woman in Sacks’s book whose case inspired Teitsson 26 Pinter’s play, dreams of being imprisoned in a castle, and this image is “virtually the same as that consciously constructed in Vladimir Bukovsky’s To Build a Castle – My Life as a Dissenter (1977), a book Pinter had read and pronounced ‘remarkable’ just a few years before writing A Kind of Alaska” (Regal 121). Just as Bukovsky’s book takes place in a prison camp (Bukovsky himself spending years in both prison camps and, tellingly, psychiatric hospitals), Deborah’s first evaluation of her whereabouts upon waking up is that she has “obviously committed a criminal offence” and is now in prison (Pinter 4.319). Deborah’s situation holds certain parallels, both general and specific, with Winston Smith’s confinement in The Ministry of Love. She poignantly describes how she has “been dancing in very narrow spaces” (Pinter 4. 326) but kept stubbing her toes and bumping her head, which brings a sense of a concrete experience to her feelings. Her lyrical account of the spatial confinement within her own mind takes on a darker resonance when she describes the spaces as “crushing” and “punishing” and that her experience was akin to “someone dancing on your foot all the time ... a big boot on your foot” (Pinter 4. 327), recalling the politically charged passage from Nineteen Eighty-Four cited earlier about a boot that is forever stamping on a human being. Furthermore, the actual sense of being restricted to the inside of one’s own head is also accurately portrayed by the inner monologue of Winston Smith: Always the eyes watching you and the voice enveloping you. Asleep or awake, working or eating, indoors or out of doors, in the bath or in bed – no escape. Nothing was your own except the few cubic centimetres inside your skull. (Orwell 31-32) To reinforce the theme of imprisonment, Deborah at one point goes into a sort of cowering trance where she seems to believe that walls are closing in on her, but also that people are putting shackles on her: “They’re closing my face. Chains and padlocks. Bolting me up.” (Pinter 4.340) Teitsson 27 In another instance of A Kind of Alaska echoing Nineteen Eighty-Four, Deborah sinks to a profane horror in an unpredictable stream-of-consciousness rant at her siblings: People don’t want to see their sisters. They’re only their sisters. They’re so witty. All I hear is chump chump. The side teeth. Eating everything in sight. Gold chocolate. So greedy eat it with the paper on. Munch all the ratshit on the sideboard. (Pinter 4.320) This passage, which culminates in a primal disgust of rats, recalls the fact that Room 101 in The Ministry of Love contains the worst thing in the world, in Winston Smith’s case rats. It also illustrates that A Kind of Alaska is not a safe and comfortable dream-zone, but a disorientating and horrifying place, as indicated by the link to Bukovsky’s experiences in the Soviet Gulag system. Deborah’s doctor, Hornby, holds the power to dismay her by matter-of-factly pointing out her physical state as she is in his keep, which O’Brien also does to Winston Smith. Hornby also assures her that better times lie ahead by saying that there will soon be a party for her (Pinter 4.326), although the sinister political connotations of the word “party” when uttered in a Pinter play render the promise ambiguous at best. Later in the play, Hornby even tells Deborah that there will be a birthday party (Pinter 4.338), which can justly be seen as an invitation to the reader to recall the fate of Stanley Webber. The relationship between Deborah and Dr. Hornby is comparable to O’Brien’s absolute stewardship of Winston Smith’s fate, in which the dominating party sees fit on occasion to console the prisoner with a grim promise: ‘It might be a long time,’ said O’Brien. ‘You are a difficult case. But don’t give up hope. Everyone is cured sooner or later. In the end we shall shoot you.’ (Orwell 314) Teitsson 28 Just like Nineteen Eighty-Four (and, it is implied, The New World Order), A Kind of Alaska then ends with acceptance and gratitude on the part of a suffering individual after a long period of confinement and chronological disorientation. Although critics had a hard time coming to terms with what they saw as an anomaly in Pinter’s work, A Kind of Alaska being based on factual reporting by another author rather than being Pinter’s fantasy from the start, the play does in fact contain many of the typical Pinteresque elements of temporal dislocation, enclosed spaces and connotatively charged phrasing. As A Kind of Alaska deals with a submerged consciousness, Pinter’s political sensitivity lurks beneath the surface, occasionally peeking through by way of a telling selection of words, such as “criminal offence”, “prison”, “punishing” and “padlocks”. In this way, the political implications of a psychological state emerge. Winston Smith deals with the same problem of an outside Other in Nineteen EightyFour, the nemesis being the Party, and his level of identity and self-expression is directly related to the security of his room. The layout of his flat, with its one corner out of sight of the telescreen, gives him the small degree of privacy from his enemies and watchers. The enterprise of writing a diary which this situation enables is however ultimately unfulfilling and he ends up compulsively writing anti-establishment slogans instead of finding solace in writing. The ideal set-up to Smith is the room he rents from Mr. Charrington, which appears to have the unique feature of being entirely telescreen-free. Until Smith and Julia’s illusion is shattered, they find peace in the room, forgetting time. The Pinteresque theme of a person in an enclosed space defending itself against outside forces applies to Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four in that, as indicated earlier in this essay, his physical space is gradually circumscribed as his enemies tighten their hold on him. Moreover, as discussed later in this chapter in relation to Pinter’s A Kind of Alaska, Smith’s mental space is restricted and ultimately obliterated as he loses the political and psychological fight for his mental autonomy. Teitsson 29 Language as a Weapon Language is a weapon that is used for exciting tactics in a series of human encounters. Speech is warfare, fought on behalf of thoughts, feelings and instincts. (Brown 18) Language in Harold Pinter’s plays is paradoxical in that critics have both claimed that it reveals and hides the underlying message and motives of the author and the characters. Almansi claims nihilism on the part of Pinter and blames language: Like many of his contemporaries on the continent, Harold Pinter is a writer who refuses to broadcast a message to the world. He is an author without authority, a communicator in the paradoxical position of having nothing to say. [...] For him, as for the post-modernist world generally, it is language that provides the supreme obstacle. (Almansi 11) Billington, on the other hand, seems to believe that Pinter sees language as a tool to bring actual meaning out of supposedly random or nonsensical situations: [...] what Pinter sees is that the language we use is rarely innocent of hidden intention, that it is part of an endless negotiation for advantage or a source of emotional camouflage. (Billington 124) These two viewpoints may in fact be two sides of the same coin in the meaning that the language of Pinter’s characters is a key to their essence. Just as responsible modern people must train themselves in a linguistic manner to see through the various lies and halftruths that appear before them daily in the media, Pinter certainly believes that his audience should approach his plays with a critical ear and try to infer the true motives of their characters by paying attention to their words no less than their deeds. In other words, the audience should seek to understand the ‘linguistic personality’ that each of the characters in a play such as The Birthday Party is infused with (Pinter: A Study of His Plays, 86). The Teitsson 30 reason for this analytical necessity is political; words can be used as weapons of subjugation. Language and its use are central to the long-debated question of meaning in The Birthday Party, which was referred to earlier in this chapter. The play starts with the verbal duel between Meg and Petey which is mentioned above, in which she “wishes to make him acknowledge her presence and his dependence” (Brown 22) by repeating her questions (“Is that you?”), even when they refer to different things, be it about the niceness of cornflakes, the weather or fried bread. This rather simple stratagem is also aimed at reinforcing words and perceptions to control the conversation, conferring upon it a banal yet insistent quality in keeping with Meg’s character. Her conversation is “the paradigm of existentialist chat, whereby you talk about nothing (or about the weather) in order to make sure that you exist – and that other people are aware of it” (Almansi 43). Petey, on the other hand, tries to assert himself in his own way by “disclosing as little as possible, protecting himself, holding himself still” (Brown 24). He also has a tendency to light rebellion against authority, as shown in his feeble encouragement to Stanley to resist as the latter is being led away, but which manifests itself at the beginning in a little quip when Meg asks if Stanley is up: PETEY. I don’t know. Is he? MEG. I don’t know. I haven’t seen him down yet. PETEY. Well then, he can’t be up. MEG. Haven’t you seen him down? (Pinter 1.4) Although Meg is much the more assertive of the two, the above exchange shows that in the verbal battle of wills, Petey will also seize every chance he gets to twist her words, even when Meg will routinely turn his little revolt against him with a question as above. Teitsson 31 Stanley puts up stronger resistance than Petey to Meg’s mind-numbing patter, taking the initiative on occasion. When Meg asks the more intellectually inclined Stanley whether the fried bread was nice, just as she asked Petey, Stanley counters by describing it as “succulent”. This one word brings the expected reaction; Meg perceives the word as naughty or even erotic. By this stratagem, Pinter simultaneously draws attention to the Orwellian power of word connotation and points out that unlike the proletarians Meg and Petey, Stanley is a middle class intellectual, which would place him as an Outer Party member in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The outstanding feature of Goldberg’s verbal expression is its capacity to confuse while being delivered in an authoritative manner. The discrepancies of time in his reminisces have been discussed earlier in this chapter, but he also has a way of dehumanizing characters by merging them. Goldberg describes Meg with the exactly same words as he describes his mother and his wife, just as he uses nearly identical phrases for different reminisces of coming home for his dinner (Gale 46). Taken together with the various names he uses for himself and for McCann, these convergences point out that Goldberg’s mission with language is not just to diminish other people’s sense of time, but to strike a blow to personal identity. These two factors echo the motives of O’Brien, Goldberg’s counterpart in Nineteen Eighty-Four, and his attacks on Winston Smith as an enemy of the Party, based on time and identity. Esslin points out an ominous exchange between Stanley and Meg early on in The Birthday Party, where he teases her with a threat of “them” coming today with a “wheelbarrow” in “the van” (Pinter: The Playwright, 73). The implication is that death is in the air, the wheelbarrow symbolising a coffin just as Goldberg’s black car later on represents a hearse, taking away the broken shell of a man that Stanley has become. Stanley could be threatening Meg, or he could be projecting his own fear of being taken away to his certain death. In the end, the parallel to Nineteen Eighty-Four holds sway when it comes to Teitsson 32 the object of oppression, as it is in fact the sensitive artist Stanley, and not simple housewife Meg, who is the target of the mysterious oppressors. There’s no need to worry about the proles, but the intellectuals must be crushed: “As the Party slogan put it: ‘Proles and animals are free.’” (Orwell 83) Although Stanley Webber and Winston Smith have enough powers of rebellion and mental capacity to make them objects of a totalitarian clampdown within their own respective stories, their faculties of expression have their limitations, and so they have the weakness that they are prone to succumbing to verbal assaults as well as physical ones. As the protagonist of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith’s inner thoughts and feelings are presented at length throughout the novel. Apart from his intellectual battles with O’Brien in the last part of the book, he reflects on his everyday life and its relentless tedium, tries to remember his mother, and even goes so far as to write a diary in defiance of the Party, where he slides into rage on a par with Hate Week by writing “DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER” repeatedly in capitals (Orwell 20). To a slightly larger degree than Stanley, Smith is normally fairly articulate; after all, his trade is writing articles and editing text, not playing the piano. Faced with the twisted logic and dexterity of his captor, however, Smith loses faith in any prospect of debate: “His mind shrivelled as he thought of the unanswerable, mad arguments with which O’Brien would demolish him.” (Orwell 297) In the case of Stanley, the regression of articulation reaches a comparably primeval level, as by Goldberg and McCann’s assault on his senses he is literally rendered speechless as described by Pinter: Stanley fights for his life, he doesn’t want to be drowned. Who does? But he is not articulate. [...] In the third act Stanley can do nothing but make a noise. What else? What else has he discovered? He has been reduced to the fact that he is nothing but a gerk in the throat. But does this sound signify anything? It might very well. I think it does. He is trying to go further. He is Teitsson 33 on the edge of utterance. But it’s a long, impossible edge and utterance, were he to succeed in falling into it, might very well prove to be only one cataclysmic, profound fart. You think I’m joking? Test me. In the rattle in his throat Stanley approximates nearer to the true nature of himself than ever before and certainly ever after. But it is late. Late in the day. He can go no further. (Various Voices 14) In Esslin’s words, this is “the speechlessness of annihilation, of total collapse” (Pinter: A Study of His Plays, 239). When the power to shape thoughts into words is gone, so is all autonomy of the self. In the dystopian society of Nineteen Eighty-Four, language is wont to take on a paradoxical quality to a no lesser degree than in a Pinter play. In the first chapter, the three slogans of the Party appear for the first time of many: WAR IS PEACE FREEDOM IS SLAVERY IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH. (Orwell 6) The four ministries of Oceania are named after the opposite of their function: “The Ministry of Peace concerns itself with war, the Ministry of Truth with lies, the Ministry of Love with torture and the Ministry of Plenty with starvation.” (Orwell 246) Society is so saturated with the discourse of the police state that even children habitually use terms like “traitor” and “thought-criminal” (Orwell 27). An absurd element shines through at one point in the terminology of the daily exercises dictated through the telescreens, which are called the Physical Jerks (Orwell 36), as if non-physical activity could involve jerks. The importance of language as a political tool for controlling thought processes is so highly valued by the ruling Party that a new language, Newspeak, is being developed to take the place of English. Beneath all communication lies a thought process of reality Teitsson 34 control, or Doublethink as it is termed in Newspeak. The purpose of the language is detailed in the Appendix: The purpose of Newspeak was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to the devotees of Ingsoc, but to make all other modes of thought impossible. It was intended that when Newspeak had been adopted once and for all and Oldspeak forgotten, a heretical thought – that is, a thought diverging from the principles of Ingsoc – should be literally unthinkable, at least so far as thought is dependent on words. (Orwell 343) In other words, language was a weapon to determine political thought. The Orwellian notion of diminishing language in order to circumscribe thought processes is political in nature, as is the Pinteresque equation of Stanley’s speechlessness signalling the end of his rebellion against authority. This is the starting point of Pinter’s adaptation of Orwellian modes of expression to the stage, along with the silences and pauses that he was to become known for. In this way, Harold Pinter condensed Orwell’s vision and made it accessible for the second half of the twentieth century. Teitsson 35 Conclusion Themes which critics generally agree to be at the forefront of Harold Pinter’s plays, such as revision of the past in order to control the present, enclosed spaces, intrusion into such spaces, and a manipulation of language aimed at dominating other characters, are also prominent features of George Orwell’s final statement, the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. ReStarting with Pinter’s first major work, The Birthday Party, first staged nine years after the publication of Orwell’s novel, Pinter’s output consistently shows features which point to his thematic debt to Orwell, which critics have largely left unacknowledged until now, except in relation to Pinter’s most overtly political plays of the nineteen-eighties, such as One for the Road and Mountain Language. Pinter’s defining themes have a strong common thread of psychological conflict between characters, which can be seen in a political context as a theatrically constructed microcosm of a political struggle on a larger scale. With Pinter’s emergence less than a decade after Orwell’s death in 1950, the mantle of Orwell’s political writing was passed on in a different form. Teitsson 36 Works cited Alexander, N. “Past, present and Pinter”. Essays and Studies. London: English Association, 1-17, 1974. Almansi, Guido; Henderson, Simon. Harold Pinter. London: Methuen & Co., 1983. Beckett, Samuel. The Complete Dramatic Works. London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1990. Billington, Michael. Pinter. London: Faber and Faber, 2007. Brown, John Russell. Theatre Language: A Study of Arden, Osborne, Pinter and Wesker. London: Allen Lane The Penguin Press, 1972. Byczkowska-Page, Ewa. The Structure of Time-Space in Harold Pinter’s Drama: 1957-1975. Wroclaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wroclawskiego, 1983. Cambridge Review, The. “From the Cambridge Review”. The Cambridge Review, April 1958. 25 April 2011. http://www.haroldpinter.org/plays/plays_bdayparty.shtml Dobrez, L. A. C. The Existential and its Exits: Literary and philosophical perspectives on the works of Beckett, Ionesco, Genet and Pinter. London: The Athlone Press, 1986. Dukore, Bernard F. Harold Pinter. 2nd. Ed. London: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1988. Esslin, Martin. Pinter: A Study of His Plays. London: Eyre Methuen, 1977. Esslin, Martin. Pinter: The Playwright. London: Methuen & Co, 1970. Esslin, Martin. The Theatre of the Absurd. London: Methuen, 2001. Gale, Steven H. Butter’s Going Up: A Critical Analysis of Harold Pinter’s Work. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1977. Teitsson 37 Hobson, Harold. “The Screw Turns Again.” The Sunday Times. May 1958. 25 April 2011. http://www.haroldpinter.org/plays/plays_bdayparty.shtml Lowenthal, David. The Past Is a Foreign Country. Cambridge University Press, 1988. Orwell, George. Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Pinter, Harold. Plays 1. London: Faber and Faber, 1991. Pinter, Harold. Plays 4. London: Faber and Faber, 1993. Pinter, Harold. Various Voices. London: Faber and Faber, 2005. Raby, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Regal, Martin S. A Question of Timing. London: MacMillan Press, 1995. Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Ware: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1992. Simpson, J.A., Weiner, E.S.C. (ed). The Oxford English Dictionary (second edition). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989. Smith, Ian [ed.] Pinter in the theatre. London: Nick Hern Books, 2005. Svenska Akademien. The Nobel Prize in Literature 2005 - Bio-bibliography. Nobelprize.org. 25 April 2011. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/2005/bio-bibl.html