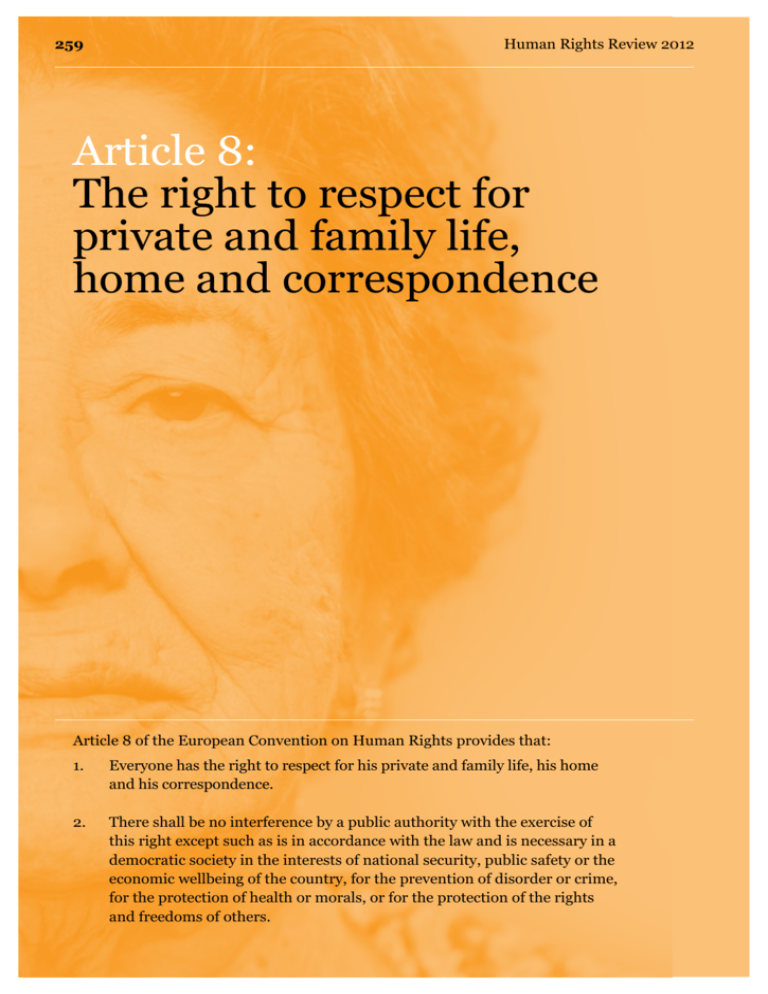

Article 8: The right to respect for private and family life, home and

advertisement