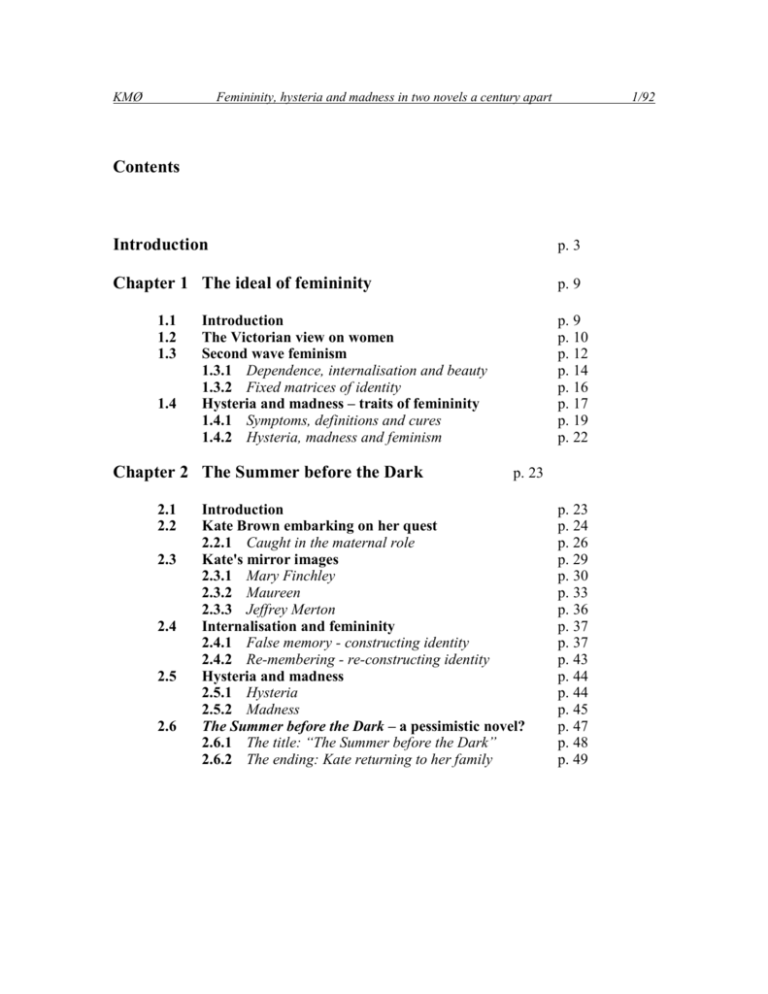

Contents Introduction Chapter 1 The ideal of femininity Chapter 2

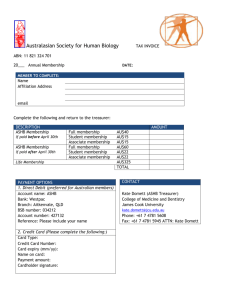

advertisement