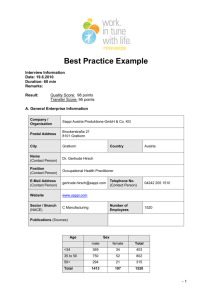

Motivation for employees to participate in workplace health promotion

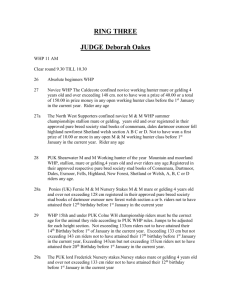

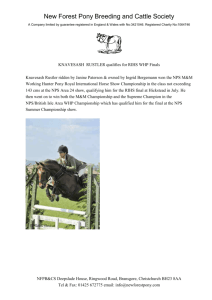

advertisement