Communication Skills.

advertisement

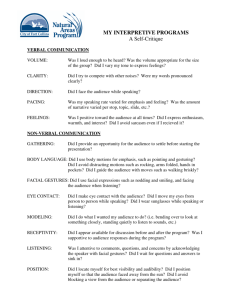

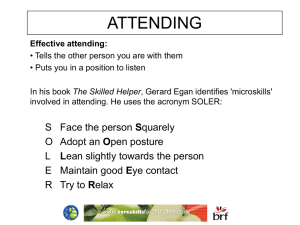

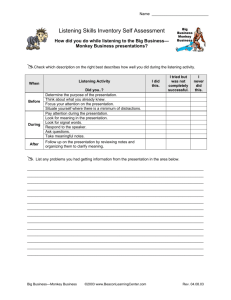

Module 11 Communication Skills Download this module: www.transact.nl Module 11 Communication Skills 11a Content and Comments This module contains a selection of explanations of communication styles and exercises, as well as some basic exercises like how to discuss a case. The format differs slightly from the other modules. The exercises can be used for a specific training on communication skills, but they can just as well be used as an integral part of any other training. 11b Objectives to understand the importance of verbal, non-verbal and para-verbal communication. to explore personal experiences with non-verbal communication. to learn about basic communication skills. to distinguish active listening responses from non-listening responses. to introduce and practice with open ended questions. to define paraphrasing and summarizing. to apply paraphrasing and summarizing. to understand the advantages of “I” statements. to learn about reframing through examples and exercises. to define the characteristics of good feedback. to practice constructive feedback. 11c Suggested Training Schedule Part I Verbal and Non-verbal Communication time in minutes 11.2 Exercise: Para-verbal Communication 15 11.3 Exercise: The Sound of Silence 15 11.4 Presentation: Non-verbal Communication 11.5 Exercise: A Hand Story 30 11.6 Exercise: Verbal and Non-verbal Communication 15 11.7 Exercise I’m Happy, I’m Miserable 15 Part II Basic Communication Skills 11.8 Exercise: Following Directions 11.9 Presentation: Active Listening 11.10 Exercise: Active Listening (1) 11.11 Exercise: Active Listening (2) 11.12 Exercise: Listening for Feelings Part III Listening to Clients 11.13 Presentation: Listening to a Client 11.14 Exercise: Non-listening Responses 11.15 Presentation: Listening to a Client Continued 30 30 30 30 45 Admira Module 11 3 11.16 Presentation: Open-Ended Questions 11.17 Exercise: Open-Ended Questions Part IV More Communication Skills 11.18 Presentation: Paraphrasing 11.19 Exercise” Paraphrasing (1) 11.20 Exercise Paraphrasing (2) 11.21 Presentation: Summarizing 11.22 Presentation: “I” Statements 11.23 Exercise: “I” Statements (1) 11.24 Exercise: “I” Statements (2) 11.25 Presentation: Reframing 11.26 Exercise: Reframing 11.27 Presentation: Feedback 11.28 Exercise: Feedback 11.29 Presentation: Receiving Feedback 11d Ideas and Suggestions for Trainers 45 30 30 30 30 45 45 Ideally, the trainer(s) is (are) skilled in communication training The exercises can all be done in about two days, but they could also be included in other trainings It is possible to do some physical exercises in between From time to time, in between exercises, there should be some discussion on how the participants can use these exercises in their work. 11e Training Material Overhead projector and sheets Handouts A collection of picture postcards 4 Admira Module 11 11 Content of the Module on Communication Skills Part 1 Verbal and Non-verbal Communication 11.1 Introduction When we start planning group- or individual work, in both psychosocial programmes and any other activity around helping and working with people, it is a great advantage to be acquainted with basic communication skills. This is especially relevant for counselling and/or therapeutic work. Unfortunately, good communication is not taught at school, the education system is not directly aimed at more successful communication. Consequently, the majority of people communicates by means of what they pick up in everyday life, sometimes more, sometimes less successful. Verbal, non-verbal and para-verbal communication When we talk about communication amongst people in general, we need to bear in mind that communication consists of three basic segments: verbal, non-verbal and para-verbal. Verbal Communication Verbal communication has to do with the contents of what we are talking about, the words that are spoken. Para-verbal Communication Para-verbal communication represents the way we speak. We send messages through the strength, tone and colour of our voice, and with the speed of our words and sentences. All of these elements significantly influence the way we are interpreted. Our listeners discern our mood and the state we are in through pauses in speech, trembling of our voice, its strength and firmness 11.2 Exercise: Para-verbal Communication (15 min) Objective: To become aware of para-verbal communication. Steps: 1. The trainer thinks of a sentence (for example, “Today is a beautiful warm and sunny day and I feel really good,”) that the students then have to repeat out loud in different ways, changing: tone (monotone, flat, lively, different intonation, hesitantly, trembling, broken) speed (fast, medium, slow) volume (loud, medium, soft) diction (clear or unclear pronunciation, different regional accents) 2. Discuss the exercise: What did you notice about the different ways of repeating the sentence? How did speed affect the meaning of the sentence? How does the same sentence come across when uttered loudly or very quietly? Another important aspect of para-verbal communication, which is rarely mentioned, is pauses in a client’s speech, which can last from seconds to several Admira Module 11 5 minutes. Pauses can either be negative and rejecting or positive and accepting. It is impossible to pin down exactly the meaning of all pauses, but the following are the most frequent reasons: the client has reached the end of a thought anxiety, embarrassment the client is experiencing some particular painful feeling which she is not ready to share the client leaves an “anticipatory” silence when expecting something from the counsellor (information, support, interpretation, reassurance) the client is thinking over what she has just said the client is recovering from fatigue of a previous emotional expression 11.3 Exercise: The Sound of Silence (15 min) Objective: To encourage listening skills and the enjoyment of silence. Material: A series of picture postcards. Steps: 1. All participants sit quietly in a circle and focus to hear the most distant sound outside the room. Then spend a minute or two listening to a sound from inside the room. Finally, everybody listens to the sounds from their own bodies and thoughts. Afterwards everyone in the group shares their experience: What was it like to be quiet? Was it hard? How often are you quiet? How often do we actually hear little sounds? What happened when you listened to your thoughts? 2. The pictures are distributed around the room for everyone to see and all choose one that impresses them in some way. Now, the participants form pairs and explain to their partners why they chose this particular picture. Each takes their turn to speak for 3 to 5 minutes while the other encourages her to talk without interruption. 3. Get back into one group again and discuss the exercise: What was harder for you: speaking or listening? What was it like to be heard? How did it feel to listen for 3 minutes without interrupting the speaker? How well did your partner listen? How often do other people really listen to you? How often do you really listen to other people? 11.4 Presentation Non-verbal Communication Through non-verbal communication we send out a great number of messages about how we feel, what we think and our reactions to people from our surroundings or a particular situation. In order to basically understand this 6 Admira Module 11 concept, it is useful to divide non-verbal communication into communication through body signals and the communication through the surroundings. Non-verbal communication behaviour through the body: eye contact - looking at a specific object, looking down, looking steady at the helper, shifting eyes from object to object, covering eyes with hands eyes - tears, “wide-eyed” skin – looking pale, blushing posture - indicator of alertness or tiredness, “eager” and ready for activity, crossing legs, arms crossed in front, hanging head facial expression - stoical, wrinkling forehead or nose, smiling, biting lip hand and arm gestures - symbolic gestures, demonstration of how something happened repetitive behaviour - tapping foot or fingers, trembling, playing with button or hair Non-verbal communication behaviour with regard to the environment: distance - moving away (or forward) when another person moves closer position in the room - moving around the room, protecting self by having objects (e.g. desk, table) between self and other person, sitting position (in the centre of the room, side by side) clothing - neat, untidy, casual/formal, warm/cold colours, lively/ dull, expensive/ Spartan 11.5 Exercise: A Hand Story (30 min) Objective: Explaining non-verbal communication through one of its forms. Steps: 1. The group splits up into smaller groups (ca. four per subgroup, preferably persons who do not know each other but would like to become acquainted). The subgroups sit in small circles, hands lightly folded in their laps. The trainer gives the following instructions: Close your eyes and get in touch with your body... Notice what is going on inside your head... Become aware of you breathing... Notice tension or discomfort... See if you can become more comfortable... Now bring your hands together as if they were strangers... Let them discover each other... What are the hands like...? Let your hands rest again... Open your eyes. Reach out to the hands of the persons on both sides of you.... Be aware of your thoughts, images, and fantasies... Say hello with your hands... Gently try to get to know these hands... Try to express different feelings and attitudes through your hands: express playfulness be caring and tender be active express arrogance be timid express anger Admira Module 11 7 be loving express irritation express joy act depressed express happiness 2. Come back to the large group again and discuss: How did you feel holding your partners’ hands? Were you able to convey the assigned emotions with your hands? Were you able to feel the other ones’ feelings through your hands? What feelings were the easiest to receive? What feeling was the easiest to express with your hands Non-verbal Communication The position of our body while we talk, gestures, movements, eye contact, colour of voice, all these signals emphasize, or sometimes even shape the way our message is understood. Although we often presume that the content is the basis of what others pick up from us, this is only true if our verbal, para-verbal and non-verbal messages are in accordance. However, when the spoken part of a message is in discord with the position of the body and colour of voice, the interpreted meaning of the message changes significantly. Research has shown that the content of a speech makes for only 30 percent of the message, while the listener, consciously or unconsciously, grants more importance to para-verbal and non-verbal messages. 11.6 Exercise: Verbal and Non-verbal Communication (15 min) Objective: To become aware of the verbal, non-verbal, and para-verbal aspects of communication, and to recognise messages where these three aspects do not agree. Steps: The trainer or one of the participants thinks of a sentence that is as simple as possible (for example, “I’m glad to be here with you today and I hope we have a good and productive day”). This sentence is expressed in three different ways: Sit in a comfortable, open position (legs and arms not crossed), smile, look the others in the eye, loudly, clearly, and cheerfully utter the sentence. Pronounce the sentence just like the first time – happy, loud, and clear – but sit with your legs and arms crossed and look at the floor. Sit with your legs and arms crossed, look at the floor, slowly rock back and forth, hang your head, and in a quiet, shaky voice, almost as if you were about to cry, say the assigned sentence. The discussion: When did you most believe in the words? What led you to believe it? What led you to not believe it? What was your impression of the second way of expression (the non-verbal message did not agree)? 8 Admira Module 11 What was your impression of the third manner of expression (the non-verbal and the para-verbal message did not agree with the contents)? Exchange personal experiences – When did our own messages “disagree” or when did we notice that someone’s verbal and non-verbal messages were different? 11.7 Exercise: ‘I’m Happy, I’m Miserable’ (15 min) Objective: To illustrate discrepancies between verbal and non-verbal communication. Steps: All participants sit in a circle. One player turns to her neighbour and begins by saying either: “I’m very happy,” while making a miserable face, or by saying: “I’m very miserable and sad,” with a very big smile. Continue around the circle, with everyone carrying out the assignment as well as they can. Discuss: How do you feel about this exercise? Was it difficult for you to say that you are happy while making a sad face? What was more important, the words or the facial expression? Explanation: Leading theorists and practitioners in this field hold that non-verbal behaviour should be seen as a key to the emotions and motives of a person that are beyond behaviour or reactions. The advisor should bear in mind that the same behaviour in two different people does not mean the same; it does not mean the same even with the same person in two different situations (cultural, social or situational differences). Non-verbal behaviour reveals additional information about a client, her feelings and thoughts to the counsellor. Often, a client sends one message through words and a completely different one through her body, voice or facial expressions. Providing feedback to a client about her non-verbal behaviour helps her to become conscious of that behaviour and encourages her to share with us those important and unstated feelings. Apart from being skilful in observing and reacting to non-verbal messages of a client, a counsellor should also be conscious of the influence of her own nonverbal behaviour towards the client. It is important for the counsellor to create natural, relaxed and genuine eye contact, to sit openly, without obstacles between her and a client and to assume a relaxed and natural body position. Admira Module 11 9 Part II Basic Communication Skills In this section we will discuss basic communication skills: active listening, openended questions, paraphrasing, summarizing, “I” statements, reframing and giving or receiving feedback. The following skills are at the basis of the therapeutic/counselling process and used by most counsellors and therapist regardless of their particular theoretical orientation. 11.8 Exercise: Following Directions (30 min) Objective: To illustrate communication difficulties. Material: (Handout 1) One for the demonstration, enough copies for all pairs. Handout 1- DIRECTION FOLLOWING Samples of few simple pictures: Steps: The group splits up in pairs. One of each pair takes a picture and gives instructions to the other to reproduce it. No short cuts, such as descriptive phrases, are allowed. The participant describing the picture should not be able to see the drawing until it is finished. Wait until everyone is done and compare your results. The partners switch roles. Discussion: Was it easy or difficult to get the picture just right? Why? Did you receive clear and good instructions? Do you think that you gave clear and good instructions? Did you find that at times your partner was unable to understand what you meant even though it seemed perfectly clear to you? 11.9 Presentation: Active Listening Active listening is the first condition for proper and especially successful communication. Its basic component is comprehensive listening. The well-known psychotherapist C. Rogers says it is done through “thinking with a client”, and not “thinking about a client” or “thinking instead of a client”. To do this we need 10 Admira Module 11 to follow the constant verbal, para-verbal and non-verbal messages of our client which requires a high level of concentration and appropriate reactions to show the client that she is really heard and to serve as an incentive for continuing and deepening communication. Active listening demands full attention. Problems and attitudes can be expressed in a number of ways, and it is up to us to “tune in” to all of these channels – non-verbal communication (position of the body, gestures, long pauses, speed of delivery), voice (tone and colour), and actual words. 11.10 Exercise: Active Listening (1) (30 min) Objective: To be aware of how we feel when someone listens to us or does not listen to us. Steps: The group splits up in pairs. Each pair has a Person A and a Person B. Person A starts by talking for 4 minutes about something that is significant in her life at the moment. Meanwhile Person B listens carefully for two minutes (trying to show her partner non-verbally that she believes that what person A says is important). The remaining two minutes person B does not listen at all (and makes every effort to show that she is not listening). They change roles. Return to the large group and discuss the exercise: How did you feel when the other person listened to you carefully? How did you know that she was hearing you? In what way did she show that she was listening to you? How did you feel when the other person did not listen to you? How could you tell that she was not listening to you? 11.11 Exercise: Active Listening (2) (30 min) Objective: To encourage listening skills. Material: A collection of different postcards distributed around the room. Steps: The pictures are distributed around the room in a way that everyone can see them and all participants choose one that impresses them in some way. The group splits up in pairs and each person has 3 to 5 minutes to try to explain why she picked a particular postcard. The listener will encourage her to speak without interruptions. Then the partners change roles, the listeners become the speakers. Return to the large group and discuss: What was harder for you, speaking or listening? What was it like to be listened to? How did it feel to listen for 3 minutes without interrupting? How well did your partner listen? How often do other people really listen to you? How often do you really listen to other people? Admira Module 11 11 11.12 Exercise: Listening for Feelings (30 min) Objective: To identify the feelings behind what is actually said. Steps: The group splits up in pairs. The couples talk to each other about something that is important to them (for example a relationship, a problem, their job) for about three minutes. After the first person has spoken for three minutes, the listener has one minute to describe the feelings that she imagines the speaker has about the subject. The couples change roles. Still in pairs the participants discuss how the exercise felt and where they agree and disagree about the feelings that were identified. 12 Admira Module 11 Part III Listening to Clients 11.13 Presentation: Listening to a Client Listen carefully to the client. Your direct attention should be focussed on: a) Content (words, the story behind the problem) b) The meaning of unfinished sentences (“And then he did THAT to me.”) c) What is not being said d) Speed/tardiness in delivery e) Pauses in speech f) Contradictions, ambivalence, paradoxes g) Changing of the subject during the conversation h) Feelings (whether the woman states them herself, or they are not actually voiced in words) i) Your own reaction to what the woman is telling you You know you are not actively listening when: you order your client what to do (“First you apologize and pack your things, we will discuss everything later.”) you scare your client (“If you do it that way, all sorts of things will happen.”) you moralize and/or lecture (“It is best for children to have both parents and you will deprive them of that.”) you give cut-and-dried answers or solutions (“In such situation, it is best to stop all previous contacts, go to a social worker, file for a divorce, etc.”) you criticize, estimate and judge the client or her behaviour (“What you have done was neither wise nor responsible.”) you interpret her words in your own way (“You say your marriage is bad, that means he neglects and physically abuses you.”) 11.14 Exercise: Non-Listening Responses (45 min) Objective: To recognize it when people respond in ways that indicate they aren’t listening, and also to demonstrate how it feels not to be listened to. Material: Small text for role-play exercise. Steps: 1. The trainer reads a text (or creates a role-play scenario with a member of the group) to demonstrate a non-listening response, for example: Anna: My day was a complete disaster. Mom: Please, honey, not now, I’m trying to get this cleaning done. Anna: My boss started shouting at me in front of everyone. Mom: I’m sure that she had good reason. Anna: Well, I don’t know the reason. Mom: I’m sure she knew it. Anna: It was really hard for me. Mom: You’ll have forgotten about it tomorrow. Anna: I am so embarrassed. Mom: Oh, you’re such a pain to me and your father. Admira Module 11 13 Other situations for role-playing are also possible (non-listening responses between friends, colleagues at work, or between partners). 2. After the exercise have a discussion with the group: What types of non-listening responses do we use every day? Why do we use them? Identify other types of non-listening responses. How do you feel when you want to be heard and someone gives you a typical non-listening response? 3. Write all types of non-listening responses that are raised in the group discussion on the flip chart (e.g. changing the subject, being busy, switching off, being a know-it-all, brushing the topic aside, giving false hope, etc.). 11.15 Presentation: Listening to a Client Continued The only exception to the rule that says not to give advice is in crisis counselling. Here it is necessary to provide concrete information or advice on where and whom to go to for help or support. In order to develop more successful communication, after careful active listening it is useful to gather additional information (open-ended questions), to check how well you have understood what your client has told you (paraphrasing and summarizing) and to offer your own feelings and thoughts on what has been said (“I” statements). Also, sometimes it is necessary to reframe the problem for clarification, directing it towards positive aspects, enhancing better understanding and finding common positions with regard to the problem. (Sheet 2 Handout 2) ACTIVE LISTENING Active listening includes quiet listening followed by feedback to the client about the: understanding of the content acceptance of the client’s feelings 11.16 Presentation: Open-Ended questions After we have carefully listened to a person’s problem, story or account, we often have a need to obtain additional information in order to create a clearer picture of what has been said. To do this we use additional questions. Open-ended questions ask for more information than a yes or no. This type of questions opens the door to a discussion of feelings rather than facts, and encourages clients to share their concerns and explore their attitudes, feelings and thoughts. 11.17 Exercise: Open-Ended Questions (45 min) Objective: Revealing the role of open-ended questions and their uses. Steps: 1. The group splits up into threesomes. Each group has a Person A, a Person B, and a Person C. Person A speaks of the last time she had fun or took a 14 Admira Module 11 vacation. Person B asks open-ended questions in order to keep the conversation going. Person C takes notes of all the open-ended questions she observes in the course of the conversation. 2. Return to the large group and discuss: What open-ended questions were used (count them)? What effects did they have on the dynamics of the conversation? Were the questions appropriate, and were they asked in the right way? Explanation: Open-ended questions are often mistakenly understood or used as a kind of direct questions about someone’s characteristics and intimate issues. They may seem to aim at the problem in no roundabout way. Asking questions in such a way is not always productive. Moreover, they may leave our interlocutor with the impression that we are in a hurry, that we do not have the time to hear the story at the speed suitable to her. She might find the questions inappropriate and too hasty. (Sheet 3 Handout 2) OPEN - ENDED QUESTIONS Open-ended questions enhance conversation and sharing of information. It is difficult to answer them with one word (YES / NO). They require additional explanation. “Can you tell me some more about it?” “What would you like to add?” “That is interesting. I would like to know more about it.” “How will it reflect on …?” Admira Module 11 15 Part IV More Communication Skills 11.18 Presentation: Paraphrasing After we have listened to a person, it is wise to check to what extent we have understood what was said. We should always bear in mind that communication is a two-way process with two people participating. The way we listen to someone depends on a series of factors – our own mood at the moment, our level of concentration, various connotations we ascribe to the same words, etc. For that reason, allow yourself the opportunity to repeat what you have heard in your own words in two to three sentences. This way, your client is able to correct you or to add something that is important to her. She may unintentionally have left something out earlier on. 11.19 Exercise: Paraphrasing (1) (30 min) Objective: To become aware of paraphrasing. Steps: 1. The group splits up in pairs. Each pair has a Person A and a Person B. Person A speaks for five minutes about her wants and needs at this moment, and Person B actively listens, without interrupting or asking questions. Then Person B has one minute to paraphrase everything that she heard. Switch roles. 2. Return to the large group and start a discussion: How did it feel when your partner was actively listening to you? How did you know that she was listening to you? How well did your partner paraphrase your wants and needs? How did it feel when another person expressed your wants and needs? 11.20 Exercise: Paraphrasing (2) (30 min) Objective: To become aware of paraphrasing. Steps: 1. A possible variation on the exercise, “I Would Walk for Miles.” A member of the group tells what she would walk miles for. Then the next person paraphrases her statement in her own words (for example, “I heard that my colleague would walk miles for her child, a meeting with a close member of her family, her partner, to find herself, etc.”) and continues with what she herself would walk miles for. Then the next participant takes over and so on. 2. Return to the large group and begin a discussion: How difficult was it to paraphrase your neighbour’s words? Was it hard to think of your own answer while you were actively listening to the other participants? Was any reason especially unexpected? Were any reasons repeated? 16 Admira Module 11 (Sheet 4 Handout 2) PARAPHRASING To paraphrase is too repeat in short a person’s statement in your own words. It can be in the form of a question or a statement. It invites your collocutor to confirm your statement, enabling you to check whether you have understood the content correctly. “So, to my understanding ….” “If I understood correctly, you were saying …” “It seems to me that you are proposing …” 11.21 Presentation: Summarizing Apart from paraphrasing, which is used to check a part of a story or a problem, in order to achieve successful communication, we use summarizing as well. The only difference between paraphrasing and summarizing is that summarizing refers to what has been said overall. Both paraphrasing and summarizing enable us to check whether we have heard and understood correctly what our collocutor meant to say. (Sheet 5 Handout 2) SUMMARIZING Summarizing includes enumerating the key thesis, recapitulation of the conversation thus far, and reformulating a longer statement into a shorter, more direct form. It helps maintain the dialogue, secures clearness and gives room to check whether we have understood correctly what was being stated. “So, the main two things that follow from our conversation are …” “On today’s meeting, we have covered three main topics. Those are …” “So far, we have agreed on the following …” 11.22 Presentation: “I” Statements It is difficult to name the sentences that speak about our own thoughts and feelings, but the above-mentioned term has already taken root. Most important is that we are not referring to what the group thinks (“We think …”) or to how something should be done (“This is done such and so…”). We are talking about ourselves, our emotional response to a certain behaviour or situation. In that way, we avoid accusing our collocutor, and give no rise to misunderstanding or conflict. This does not mean that the sentence necessarily has to contain the pronoun I. These type of sentences express our feelings and attitudes without judging other people’s behaviour. By using these sentences, we retain the responsibility, not transfer it to others. Admira Module 11 17 11.23 Exercise: “I” Statements (1) (30 min) Objective: To learn how to use “I” statements. Steps: 1. The group facilitator describes a hypothetical situation around some problem the whole group can identify with (for example, your workplace is far from the centre of town, it’s inconvenient, small, and cold, and you don’t have the financial means to find a new one. The coordinator is angry at the donor, the organization, and at all her colleagues, because no one wants to address this problem). 2. Each member of the group makes an “I” statement about the situation (you might want to go around the circle two or three times). Discuss: Do you understand the concept of “I” statements? What effect did the “I” statements have on the group dynamics? How does it feel to give an “I” statement? 11.24 Exercise: “I” Statements (2) (30 min) Objective: To frame critical statements in a non-threatening way. Steps: 1. This exercise is about brainstorming techniques. Sit in a circle and combine your thoughts to come up with original ideas. The trainer poses different statements which the group then rephrases into “I” statements that are as non-threatening as possible. For example: Trainer: “You never listen to what I say.” Group members: “I have a problem.” “I feel like you don’t listen to me.” 2. Begin a discussion: Do the new sentences sound accusatory? Is it difficult to rephrase the sentences in this way? How do you think this would work in real life? Do you think that communicating in this way can be useful? (Sheet 6 Handout 2) “I” STATEMENTS Formula: I am + description of feelings + description of behaviour These type of messages express our personal feelings, they do not judge and do not “correct”. We are not transferring any responsibility to the other person. Such expressions do not cause defensiveness, they foster further communication and explanations. “It is hard for me to follow when you are jumping from subject to subject.” (You 18 Admira Module 11 are confused and unorganized.) “I am worried about the relations in the group and I need your help.” (You are not a team player.) “I feel bad about you not completing the report because I have promised the donor to send it.” (You never do things in time.) 11.25 Presentation: Reframing Reframing is one of the most powerful communication skills, but it also requires the most practice and exercise. It means repeating what you have heard, but reformulated so that it is based on positive values of the message and removing negative or judgmental implications. In order to successfully reframe a statement, we need to find the right meaning of the stated message and use it is as the basis for reframing. Recognizing and accepting the problem of the other person mostly enables us to move the conversation in a more positive direction 11.26 Exercise: Reframing (45 min) Objective: To become familiar with reframing. Material: Small story. Steps: 1. The leader starts with a short story: The Wise Man Once upon a time there was a king who had a strange dream. He dreamt that all of his teeth fell out. Unhappy and distressed, he gathered all of his advisors and wise men to see if they could tell him the meaning of this dream. The first wise man humbly approached the king and said, “Your majesty. It is a bad sign. It means that everyone in your family will die before you.” The vexed king dismissed the advisor that instant, and ordered him banished to a distant land. Another advisor approached and said, “O our King! You will outlive your entire family.” Sincerely pleased, the king gave the wise man a rich reward. 2. Share comments and discuss: What were your impressions of this example? Describe a time in your own life when you used reframing. What do you find difficult about reframing? In what situations do you think reframing could be helpful? (Handout 2) REFRAMING Reframing is the most complex of communication skills. It consists of several techniques. In order to reframe, we need to: Notice the positive values the message is based on Admira Module 11 19 Eliminate negative, aggressive or judgmental implications It is useful to reframe the following: need blame future past common problem individual problem worry threat “You have done that before and that is why you are suffering now.” Reframed: “It is important to know what has been happening and to see how to avoid it in the future so that it resolves to your advantage.” 11.27 Presentation: Feedback Feedback is a form of communication with another person about the effects of her behaviour on us. Whether we are able to hear and listen to feedback depends on our attitudes, beliefs, ingrained patterns of behaviour, as well as our readiness to receive criticism. However, the formulation of the feedback is very important. There are certain rules for the presentation of feedback and these make it easier to receive it as a useful suggestion for further professional development. 11.28 Exercise: Feedback (45 min) Objective: To encourage the use of positive feedback and affirmation. Steps: 1. The group splits up in pairs. Each participant in the pair introduces herself for five minutes, thereby relating some little-known facts about herself: her unusual hobby, secret talent, etc. Then all return to the large group and each participant introduces her partner by describing her experience of this introduction. The sentences should be short and clear. The participant should avoid relating every detail, but instead give their general impression of the other person (for example, “Ana is a strong person. She values accuracy and responsibility in her life. She is ready to help others.”). 2. Return to the large group and discuss: Was it easy for you to hear about your positive sides? Were you surprised to hear some of them? Did you feel good or embarrassed, and why? Does your image of yourself match what your partner said about you? Which view is better? (Handout 3) Presentation: Characteristics of good feedback: 1. Feedback is not the same as criticism. 2. Feedback describes, it does not judge. 3. Feedback is mostly made of “I” statements. 4. Information is directed to a PARTICULAR BEHAVIOUR, not the person on the whole. 20 Admira Module 11 5. Feedback refers to the SPECIFIC, not the general. 6. The aim is to provide information that can HELP the other person, not hurt her. 7. Feedback should refer to behaviour that can be changed (for instance, it should not refer to certain physical characteristics or events over which the person has no control). 8. Feedback should be about INFORMATION, not advice. 9. Feedback should be provided at the right time, ideally immediately after a certain behaviour. 10.Feedback is more useful if a person asks for it, than if it is imposed. 11.Feedback should refer to WHAT and HOW something is done, not WHY it is done. 12.After providing feedback, always check whether it was understood correctly. 11.29 Presentation: Receiving Feedback 1. Feedback helps us increase our self-awareness. 2. If you want feedback, encourage and support the person you are asking it from. 3. Try to be open for information and don’t be defensive. 4. Nothing needs to be explained or defended. 5. After receiving feedback, share your feelings with the person providing it. 6. If you are not certain you have understood the feedback correctly, ask on. Admira Module 11 21 11f Acknowledgements This Module has been developed and written by Maja Mamula of the Women’s Room in Zagreb. 11g Suggestions for Further Reading Babbitt, E., Gutlove, P. & Jones, L. (ed.), Handbook of Basic Conflict Resolution Skills. The Balkan Peace Project, MA.1994. Brammer, L.M., Shostrom, E.L. & Abrego, P.J., Therapeutic Psychology: Fundamentals of Counselling and Psychotherapy. Prentice-Hall International Editions. 1989. Brodsky, A.M. & Hare-Mustin, R. (ed.), Women and Psychotherapy. The Guilford Press, NY. 1980. Burstow, B., Radical Feminist Therapy. Sage Publications, CA.1992. Cormier, L.S. & Hackney, H., The Professional Counsellor: A Process Guide to Helping. Prentice-Hall International Editions. 1987. George, R.L. & Cristiani, T.S., Counselling - Theory and practice. Simon & Schuster Inc, MA. 1990. Leffkof, M.,Communication skills - training manual. Ars Publica, Santa Fe, New Mexico. 1993. Meyer, S.T. & Davis, S.R., The Elements of Counselling. Brooks & Cole Publishing Company, CA. 1993. 22 Admira Module 11 Sheets and Handouts Module 11 Communication Skills Communication Skills 1. Active listening 2. Open ended questions 3. Paraphrising 4. Summarising 5. ‘I’ statements 6. Reframing Admira Sheet 1 Module 11 Active listening includes quiet listening followed by feedback to the collocutor about: The understanding of the content The acceptance of the collocutor’s feelings Admira Sheet 2 Module 11 Open - Ended Questions Open-ended questions enhance conversation and sharing of information. It is difficult to answer with one word (YES/NO). They require additional explanation. “Can you tell me something more about it?” “What would you like to add?” “That is interesting. I would like to know more about it.” “How will it reflect on …?” Admira Sheet 3 Module 11 Paraphrasing To paraphrase is to repeat in short a person’s statement in your own words. It can be done in the form of a question or a statement. It invites your collocutor to confirm your statement, enabling you to check whether you have understood the content correctly. “So, to my understanding ….” “If I understood correctly, you were saying …” “It seems to me that you are proposing …” Admira Sheet 4 Module 11 Summarizing Summarizing includes enumerating the key thesis, recapitulation of the conversation thus far, and reformulating a longer statement into a shorter, more direct form. It helps maintain the dialogue, secures clearness and gives room to check whether we have understood correctly what was being stated. “So, the main two things that follow from our conversation are …” “In today’s meeting, we have covered three main topics. They are …” “So far, we have agreed on the following …” Admira Sheet 5 Module 11 “I” Statements Formula: I am + description of feelings + description of behaviour “I” statements express our personal feelings They do not judge and do not “correct”. Admira Sheet 6 Module 11 DIRECTION FOLLOWING Samples of few simple pictures: Admira Handout 1 Module 11 ACTIVE LISTENING Active listening includes quiet listening followed by feedback to the collocutor about: The understanding of the content The acceptance of the collocutor’s feelings OPEN - ENDED QUESTIONS Open-ended questions enhance conversation and sharing of information. It is difficult to answer with one word (YES/NO). They require additional explanation. “Can you tell me some more about it?” “What would you like to add?” “That is interesting. I would like to know more about it.” “How will it reflect on …?” PARAPHRASING To paraphrase is to repeat in short a person’s statement in your own words. It can be done in the form of a question or a statement. It invites your collocutor to confirm your statement, enabling you to check whether you have understood the content correctly. “So, to my understanding ….” “If I understood correctly, you were saying …” “It seems to me that you are proposing …” SUMMARIZING Summarizing includes enumerating the key thesis, recapitulation of the conversation thus far, and reformulating a longer statement into a shorter, more direct form. It helps maintain the dialogue, secures clearness and gives room to check whether we have understood correctly what was being stated. “So, the main two things that follow from our conversation are …” “On today’s meeting, we have covered three main topics. Those are …” “So far, we have agreed on the following …” “I” STATEMENTS Formula: I am + description of feelings + description of behaviour These type of messages express our personal feelings, they do not judge and do not “correct”. We are not transferring responsibility to the other person. These expressions do not cause defensiveness, they fosters further communication and explanations. “It is hard for me to follow when you are jumping from subject to subject.” (You are confused and unorganized.) “I am worried about the relations in the group and I need your help.” (You are not a team player.) “I feel bad about you not completing the report because I have promised the donor to send it. (You never do things in time.) Admira Handout 2 Module 11 REFRAMING Reframing is the most complex communication skill. It consists of several techniques. In order to reframe, we need to: Notice the positive values the message is based on Eliminate negative, aggressive or judgmental implications It is useful to reframe the following: need blame future past common problem individual problem worry threat “You have done that before and that is why you are suffering now.” Reframed: “It is important to know what has been happening and to see how to avoid it in the future so that it would resolve to your advantage.” Admira Handout 2 Module 11 Characteristics of good feedback: 1. Feedback is not the same as criticism. 2. Feedback describes, it does not judge. 3. Feedback is mostly made of “I” statements. 4. Information is directed to a PARTICULAR BEHAVIOUR, not the person on the whole. 5. Feedback refers to the SPECIFIC, not the general. 6. The aim is to provide information that can HELP the other person, not hurt her. 7. Feedback should refer to the behaviour that can be changed (for instance, it should not refer to certain physical characteristics or events over which the person has no control). 8. Feedback should be about INFORMATION, not advice. 9. Feedback should be provided at the right time, ideally immediately after a certain behaviour. 10. Feedback is more useful if a person asks for it, than if it is imposed. 11. Feedback should refer to WHAT and HOW something is done, not WHY it is done. 12. After providing feedback, always check whether it was understood correctly. Receiving Feedback 1. Feedback helps us to increase our self-awareness. 2. If you want feedback, encourage and support the person you are asking it from. 3. Try to be open for information and don’t be defensive. 4. Nothing needs to be explained or defended. 5. After receiving feedback, share your feelings with the person providing it. 6. If you are not certain you have understood the feedback correctly, ask on. Admira Handout 3 Module 11