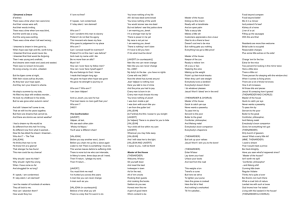

Will you join in our crusade

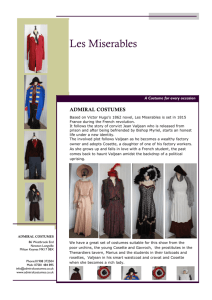

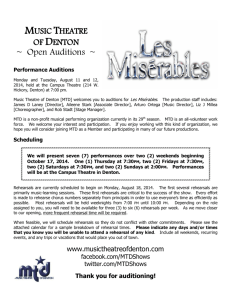

advertisement