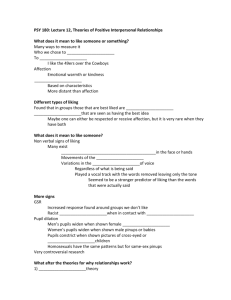

lecture outline (liking)

advertisement

Lecture 11: Liking So far we have dealt with various serious topics, from the social psychology inspired by concentration camp commandants to the the more topical isuse of violence at football matches. Now we will turn to the apparently more trivial issue of relationships, this week the topic of liking, next week the topic of loving. I say apparently more trivial because actually our relationships with people are one of the most important elements in our lives. Good relationships make us healthy as well as happy: according to some recent work by Goleman (1992), the more University room mates like each other, the fewer colds they get - more significantly the chances of surviving for more than 1 year after a heart attack are twice as high among people who get emotional support from 2 or more people. And there is also a serious social problem lurking behind the topic of liking and loving - the problem of the huge increase in divorce and family break-up. This week I’ll describe a very individualistic approach to this issue. This is essentially the traditional approach that you can find described in Aronson, chapter 8 and many other texts: You'll get some insight into current thinking if you have a look at Duck's article in The Psychologist, 8(2), 60-63, which provides a good counterweight to this work. Let's begin this week with a simple question 'Why do people like each other' and see where that takes us. If we ask people they mostly give answers in terms of the other person, like 'Julie is warm, kindly and amusing' - what this ignores is ourselves. A more accurate answer might be 'I like Julie because of how I feel when I'm with her' - or, put another way, we like people who reward us. This reward principle can be stated quite simply: that we should minimise costs and maximise rewards. From this perspective, liking and friendship are just a form of social exchange - as La Rochefoucauld (1665) put it 300 years ago "Friendship is just a scheme for the mutual exchange of personal advantages and favours whereby self-esteem may profit". 2 The perspective of exchange theory is that of the marketplace, where goods and services are traded. And so the simple economic theory of what determines transactions in a market can be applied to social transactions too. Just as an economist may talk about the price of a good, so too does the social exchange theorist talk about the price of, say, love. Gifts are not given - they are exchanged. Let's take an example of a social 'market' consisting of four friends, Dave, Pete, Bev and Sue. According to social exchange theorists, the amount of time and trouble that Dave invests in the other three will depend upon the rewards and costs involved in interacting with them. Pete is witty, energetic and plays badminton at the same standard as Dave. Bev is easy on the eye and a good cook. And Sue is extremely clever and able to help Dave with his work. Each then is potentially rewarding to Dave. But we need to take into account the costs of interaction as well as the benefits. Pete can be manic and an evening with him is risky. Bev is boring. And Sue lives some way away so seeing her involves a drive. So Dave's decision to spend time with any of these three will depend upon his calculation of the profit (that is rewards minus costs) involved in each potential interaction. Now it is obvious that the rewards and costs can consist of all kinds of things and that, in the social world unlike the economic world, there is no common scale like money. The value of all interactions then is subjectively defined and fluctuates from one time to another. Food is more valuable than a book when you're hungry; cleverness is more valuable than wit if you need help with a late assignment. Diminishing marginal utility probably applies too - just as you value your first apple more than your third, and your third apple more than your fifth, so you will be value you first evening in the week with a particular individual more than your fifth. This means that we cannot really quantify rewards and costs. This makes testing social exchange theory very difficult (though not impossible and we will come on to some examples in a moment), 3 but it doesn't necessarily undermine its usefulness as an approach. There are probably two phases in the calculation of rewards and costs. One is the estimation phase, the other the sampling phase. In estimation, we have to guess what the rewards and costs of a particular interaction might be. In sampling, we actually take part in the an interaction and sample the rewards and costs in earnest. Bev may turn out to be even more boring than Dave remembers and produce awful food - Sue may be witty as well as clever. What happens then? According to the Social exchange model, we always have one eye on the market; that is, we have a comparison level for alternatives. This is what we see as the profits potentially available in another interaction. So if the comparison level for alternatives appears more profitable than what we are actually getting, we will leave one interaction (or one relationship) and start a new one. So far I have talked about maximising profits only from Dave's perspective. But whilst Dave is making his calculations, the others are making theirs. Maybe Dave is a ghastly boring social psychologist with a penchant for talking about exchange theory. This means that social interaction is a compromise, just as the prices arrived at in bargaining are a compromise. Not only must we maximise our own outcomes but we must ensure that our cointeractants are also adequatly rewarded, else they might go elsewhere. Using an economic approach to understanding social life seems callous. Normally we talk about liking our friends and having things in common with people - we don't think about profiting from our interactions with others. But a social exchange theorist, unlike say a researcher using an ethogenic approach, who would treat respondents as experts on their own behaviour, would probably dismiss our accounts of our interactions as just rhetoric and our talk of liking, loving, getting bored etc, just our way of talking about rewards and costs. 4 So much for the bare bones of the exchange approach. Let's consider just one example of this in practice. This is unusual in that it involved a social psychological analysis of historical data. Guttentag and Secord (1984) provide an analysis of love in historical periods. According to them, the scarcity or abundance of men and women in society has varied greatly over historical time and this variation has had widespread social consequences. Men and women need each other for companionship, love, pleasure and procreation: if either men or women are in short supply, their value will increase for members of the opposite sex. Guttentag and Secord have used population data from a variety of cultures and historical periods to illustrate their argument. I will briefly describe just two, one involving an excess number of men (the rise and fall of courtly love in medieval Europe), the other involving an excess number of women. In France and Germany in the 12th and 13th centuries courtly love was practised among the upper classes. Courtly love stressed the spiritual adoration of women. To woo a maiden, the lover sang ballades that were characterised by restraint, tenderness and pledges of eternal dedication. The lady remained aloof and unattainable. Although she occasionally granted a suitor physical favours, she respected him most if he behaved in a refined and courteous manner. So the suitor would undergo considerable selfdenial to gain her attention. G & S suggest that the reason for this passion and denial was the social conditions of the time, specifically the small number of women of high social rank. The need for a large class of armed knights gave the opportunity for upward social mobility so there was an excess of noble and aspirant noble men. When the nobility closed its ranks later in the 13th century, the ratio of noble men to noble women became more equal, courtly love disappeared and a rough anti-feminism took over. 5 The second example concerns misogyny in the late medieval period. Between 1000 and 1200, the European population grew rapidly but, apparently, there was a marked change in the sex ratio, with a considerable increase in the number of women. Consistent with the exchange theory perspective, this excess of women drove down the bride-price characteristic of the earlier medieval period. But, starting around 1100, the increasing surplus of women steadily eroded the marriage rights of women - for example, the wife's right to a portion of the household property on the death of her husband was reduced. Herlihy's (1974) analysis of thousands of marriage agreements shows that bride price slowly declined and then it was followed by a rise in the dowry to be paid. This dowry increased much during the 13th and 14th centuries and finally became so large as to provoke Dante's comment (in the Divine Comedy) that the birth of daughters struck terror into their father's hearts. That men had to be paid to marry is not the only indication of the low value of women in this society. The literature of this period has exactly the kind of themes you would expect - stressing brief sexual encounters, licentiousness, reluctance of men to enter into commitment and some disparagement of marriage as an institution. So an exchange theory can provide an explanation of some historical data. It can also be used to interpret some of the empirical research into liking - so lets look at some of this. PROXIMITY. One of the most powerful predictors of whether 2 people are friends is their sheer proximity to each other. It has long been know that most people marry someone who lived or worked within walking distance. The classic demonstration of the importance of proximity is Festinger et al. (1950) who studied the development of friendship formation in student apartments. Students were allocated randomly to rooms on arrival but after a few months, when asked to name their two closest friends, 2/3 lived in the 6 same building and 2/3 of these on the same floor. A more recent and simple demonstration of this effect is the work of Segal. He studied a police academy where new recruits were assigned rooms and seats in the classroom on the basis of alphabetical order. So trainee policemen called Adams and Alton would spend more time in close proximity than trainee policemen named Adams and Young. When they were asked to name their closest friend on the course, he found that they tended to be close together alphabetically. One way of interpreting this finding is to say that if we make the reasonable assumption that on average the reward value of others was equal, it was the low cost of interacting with neighbours which lead to liking. Or, could it be that it is simply a matter of opportunity? (this seems unlikely as in the Festinger study, most people liked the person who lived one door away more than those who were 2 doors away). So why should proximity encourage liking and affection? Part of the answer is that, contrary to the proverb, familiarity does not breed contempt - rather familiarity leads to liking. Mere exposure to all sorts of stimuli - nonsense syllables, Chinese characters, pieces of music, faces - increases peoples ratings of them. Do you think the Turkish words nansoma, saricik and afworbu mean something better or worse than the words iktitaf, biwojni and kadirga? Students tested in experiments by Zajonc preferred whichever of these words they had seen most frequently. And remarkably enough, people also prefer the letter than appear in their own name - and those that appear frequently in their language. French students rate capital W as their least favorite letter - and it is also the least frequent in French. A very reasonable objection to this so-called 'mere exposure' effect, is that when you become familiar with some people you dislike them - and that some stimuli certainly lose their appeal as you get to know them - a new song which initially grows on you can become boring. And with stimuli that are boring or negative at the outset mere exposure does not breed liking. 7 However, as a broad generalization, the idea that familiarity breeds liking works quite well. We even like ourselves the way we are used to seeing ourselves. There is a neat experiment by Mita et al (1977) who photographed people and then showed them the actual picture and a mirror image of it - asked which picture they prefered most opted for the mirror image, which is of course the image that they were used to seeing. When their close friends were asked which they prefered, they opted for the true picture which is the one they were used to seeing. Myers (1994) gives a remarkable anectdotal example of this. Apparently there was an election in the states for a state court, where the sitting judge, one Keith Callow, was challenged by an unknown attorney, one Charles Johnson, simply on the principal that judges outght to be challenged. Neither man campaigned and the media ignored the contest. On election day the two names appeared on the ballot paper without any identification - the result was a victory to Johnson by 52% to 47%. The ousted judge offered the explanation that there were a lot more Johnsons than Callows - and he may well have been right. Voters may just have preferred the familiar sounding name. Bear in mind that proximity provides the opportunity for people to interact, but it is the nature of that interaction that will determine the level of liking. Most interactions are positive because people manage the impressions that they present to others - it is also true that people usually have a number of things in common with those who live or work with them - which probably explains Segal's alphabet finding. A kind of follow-up to the Festinger study was carried out in a housing estate in CA. Residents had to list the three people in the complex they liked best - and the three that they disliked the most. 61% of the most liked lived in the same building - but so did 55% of the most disliked. Those who were disliked were those who had noisy parties, let their dogs foul the pavements and so on. Which makes the point, again, that mere proximity is not enough. 8 If we move beyond proximity, we can ask 'what are people looking for in a friend? Do they look for someone with GSOH (as the lonely hearts adverts have it), someone who is sincere, who has a good character and so on? We all know that beauty doesn't matter. But though we profess this belief, in fact there is a vast amount of research showing that physical attractiveness does matter - good looks are a great asset (and I use the economic term deliberately). One classic demonstration of this effect is a large study carried out by Hatfield et al (1966). They matched over 750 first year students for a welcome-week computer dance. The researchers gave each individual personality, aptitude tests and attitude scales but then matched the couples randomly except for one constraint - they made sure that the man was taller than the woman. On the night of the dance, the couples danced and talked for a couple of hours and then, in a break, had to evaluate their partner. So the question here was what predicted liking? was it the similarity of attitudes, whether the partner was extraverted or bright or what? The researchers examined a long list of possible variables but essentially only one thing mattered - how physically attractive (as rated by the experimenters) the partner was. This applied to both men and women. The students said, of course, that they would like their partners to be intelligent - but this did not correlate at all with their preferences. Now, you may think that this is just a matter of first impressions and that physical attractiveness cannot always, or in the long term be that important. But remarkably enough, physically attractive people tend to have more prestigious jobs, earn more money and describe themselves as happier. Rosznell (1990),for instance, looked at the attractiveness of a national sample of Canadians and had interviewers rate them on a simple 5 point scale. She found that for each additional scale unit of rated attractiveness, people earned, on average, an additional $2k a p.a. A rather similar study by Frieze (1991) involved rating photos of over 700 MBA students, 9 again on a simple 5 point scale. Here for each additional scale unit of rated attractiveness people earned an additional $2.3k. This seems extra-ordinary until you remember that attractiveness will have some impact on the first impressions gained in job interviews - and that studies show that attractive children get more attention and are treated better by others - so probably have higher confidence and self-esteem as a result. Matching. There is a consensus about who is physically attractive (which seems to be the case) and there is, to put it crudely, a marketplace for attractiveness. If that is true, it is clear that not everyone can end up paired off with someone stunningly attractive - so how do people pair off? There is quite a lot of research to suggest that what happens is that people pair off with others who are as attractive as them. A number of studies have found a strong correspondence between the attractiveness of husbands and wives and of people going out together. This matching phenomenon is interesting. When choosing who to approach, again people usually approach someone whose attractiveness matches their own. In one study of dating couples, those who were most similar in physical attractiveness were the most likely, 9 months on, to still be together. And, as we might expect, married couples are more closely matched than casual dating partners. Now if one individual in a couple is not as attractive as the other, we should find that the less attractive has compensatory qualities. Each partner brings assets to the marketplace (again note the exchange metaphor) and the value of the assets creates a fair match. Lonely hearts adverts exemplify this exchange of assets there have been a few analyses of theses (for example, by Koestner 1988) and these make it clear that men typically offer status and seek attractiveness - women usually do the reverse. So we find 'attractive, bright women, 38, slender, seeks warm 10 professional male' versus 'handsome barrister, successful, seek very pretty professional lady for a significant relationship'. What is attractive? So far I have described liking and friendship in terms of exchange processes and stressed the assets, one of which is physical attractiveness, that people bring to this relationship market. But attractiveness is not an objective quality. There is though some agreement about it - attractive faces do not deviate too far from the average and symetry is important. Digitised composite faces are rated as better than 96% of individual faces and studies of those who have had cosmetic surgery have shown that this does change perceptions of attractiveness and personal characteristics. Interestingly enough, a study of girls who had orthodontic treatment also showed this effect, even though the photos used had the mouth closed. Those who are physically attractive are also seen to have other desirable characteristics, such as kindness, competence, more likely to succeed and so on (the 'what is beautiful is good' phenomenon). Eagly et al (1991) have reviewed a large number of studies on this issue and what is striking about this is that it holds at all ages, starting with infancy. For instance, Karraker found that prettier infants are considered to be more sociable and competent than poach-egg look-a-likes. The good news is that, nontheless, we also perceive likable people as attractive. There is evidence that the more in love someone is with their partner, the more physically attractive s/he finds him/here. And the more in love people are, the less attractive they find all others of the opposite sex. As Rowland (1990) put it "the grass may be greener on the other side, but happy gardeners are less likely to notice". Nearly all of the studies mentionned so far have been concerned only with first impressions and the very early stages of a relationship. It is worth asking whether attractive people are favoured in day-to-day interactions with others. 11 A study by Reis et al (1982) tried to answer this question. The participants in their study were roughly 100 undergraduates who had been rated for their attractiveness and then kept a daily record of their social activities for a fortnight. They also had to fill our questionnaires which dealt with things like their self-esteem, assertiveness in social situations and so on. Their findings are interesting and slightly surprising. Compared to unattractive males, attractive males spent more time with females and less time with males, interacted with a greater number of females, had more interactions with females and spent longer interacting with them. Attractive males were more likely to initiate an interaction with a women and felt that there was a greater degree of intimacy during their interactions. But no such relationship was found between the men's physical attractiveness and the quantity and quality of their social interactions. Attractive women were actually less likely to initiate an interaction than unattractive females and they reported that their interactions with females were more satisfying. They were also more distrustful of men. Reis' interpretation of this is that attractive men are more socially active because they are more assertive and self-confident. Attractive women, on the other hand, are not more socially active because they are unassertive. Men are reluctant to approach them as they assume (rightly or wrongly) that attractive women will reject them. Liking and friendship. You must not think, from the research described so far, its concern with physical and other assets, its emphasis on individuals seeking what is best for them, that social psychologists have ignored more fundamental issues in relationships – these will be dealt with next lecture. But two other topics which, though concerned with less superficial issues, have also been dealt with from within an exchange approach. The first is self-disclosure - the second is attitude and opinion similarity. Self-disclosure. 12 Self-disclosure is the revealing of private aspects of the self, including experiences, desires, fears, fantasies and so on, to other people. It is obviously very important in the development of relationships and, some researchers claim, important in the maintenance of long-term relationships. In one of the earliest studies of self-disclosure, Jourard found that the more intimate information that had been disclosed to someone, the more that person had disclosed back. And -the more self-disclosure there was, the greater the liking. But why The evidence suggests that the more an individual is disclosed to during an experiment, the more that they like the discloser. And the more that someone is disclosed to, the more that they will disclose back. So we see reciprocity - you disclose to me and I'll disclose to you. And it seems as if disclosing to someone is one way of giving that person something valuable (a reward) - and we already know that being rewarded leads to liking. Finally, I want to look at the importance of similarity. We know from a number of studies that people's initial liking (after one week of living in shared accommodation) does not predict very well their ultimate liking for each other. But their similarity does. How similar people's attitudes and opinions are is crucial in predicting friendship. If others have similar opinions, we feel rewarded because we presume that they like us in return - moreover, those who share our views help to validate them. But friendship is a delicate matter and Tesser (1989) has gathered evidence that students pick as friends other students who overall are about as accomplished as them, but whose accomplishments are in different domains. This maximises their chances of celebrating accomplishments whilst staying away from envy. Conclusion So how useful is the kind of exchange approach that I have outlined? Well, it seems to me that it is a fair starting point - 13 rewards and costs probably are highly relevant to liking and to social interaction generally. But since rewards and costs are idiosyncratic, this approach has limited predictive power. Furthermore, the approach is limited when the basic assumptions do not hold - for instance, when people have limited choices in their relationships because of social custom or values. In cultures other than our own, which are not so consumer oriented, exchange theory may well have very limited applicability: it is no accident that exchange theory (and the vast majority of the very research that I have described) emerged in America. But even in our society we recognise constraints on personal choice: one being the generalised belief in equity or fairness in personal relationships. Perhaps more importantly, exchange theory seems to impose a view of the world on people: some people may construe social interaction in economic terms but others may well not. And it is really the individual experiences of the social world that we need to understand - which we will come back to next week, with the topic of love.