[2006] Vol

advertisement

![[2006] Vol](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008615170_1-65572942a371191ab13cf4178fdf8ad9-768x994.png)

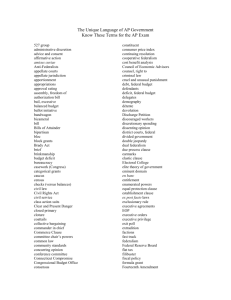

[2006] Vol. 2 LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION (COMMERCIAL COURT) 23 March; 16 May 2006 ____________________ KONKOLA COPPER MINES PLC v COROMIN LTD (NO 2) [2006] EWHC 1093 (Comm) Before Mr Justice COLMAN Insurance - Jurisdiction - Claimant insured by Zambian insurers under policy subject to exclusive Zambian jurisdiction and by English insurers under policy subject to exclusive English jurisdiction - Whether Zambian insurers should be co-defendants to proceedings against English insurers - Whether exclusive jurisdiction clause overrode need to avoid fragmentation of proceedings. KCM, a mining company incorporated in Zambia, was insured by local Zambian insurers (the NR defendants, the second, fourth, fifth and sixth defendants; and PICZ, the third defendant) under a policy covering property damage and business interruption losses. KCM's ultimate parent company took out a Global Master All Risks Policy with Coromin, its captive insurance company located in Bermuda. Coromin was reinsured by London market reinsurers. Following an avalanche in April 2001, KCM made a claim against the local insurers and also against Coromin. Proceedings were commenced in England by KCM against Coromin and the local insurers, and permission was given for service of the proceedings on the local insurers outside the jurisdiction. Coromin pleaded that it was not the direct insurer of KCM but rather was the reinsurer of the local insurers. Coromin made a Part 20 claim against its reinsurers, seeking indemnity in the event that Coromin was held to be liable either as direct insurer of KCM or as reinsurer of the local insurers. At an earlier hearing, [2006] Lloyd's Rep IR 71, the issue was whether the Part 20 proceedings by Coromin against the reinsurers should be stayed pending the determination of issues which arose between KCM, Coromin and the local insurers. The local insurers were originally included as co-defendants, although it was agreed in the course of the hearing: that KCM would commence proceedings against the local insurers in the Zambian courts; that the local insurers accepted that they were 100 per cent primary insurers of KCM, 80 per cent underwritten by the NR defendants and 20 per cent by PICZ; that in the English proceedings there should be a consent order staying the claims against the local insurers; and that stay was to remain in place until final determination of the Zambian proceedings. Two consent orders were made on 9 March 2004, both providing that in the event that the local insurers were in breach of such undertakings or agreements, KCM could apply to the court to lift the stay in the English proceedings. 446 Notwithstanding the terms of the undertakings, the NR defendants served a defence in the Zambian proceedings putting in issue the agreed proportions of the risk and reverting to their original assertion that the local insurers were collectively on risk only in respect of 10 per cent whereas Coromin was on risk for 90 per cent. PICZ similarly denied that it had accepted 20 per cent of the risk. The NR defendants and PICZ were in breach of the terms of the consent order and were in contempt of court. The NR defendants consented to the lifting of the stay of the English action and PICZ offered to purge the contempt by amending the Zambian defence. Following the lifting of the stay, the question became whether the NR defendants and PICZ were entitled to have the service of the English proceedings against them set aside. The NR defendants argued that there was an exclusive Zambian Law and Jurisdiction clause in the Zambian contract, in that the cover note provided for "Local Law and Jurisdiction Clause", and that there were no strong reasons for departing from the clause. -Held, by QBD (Comm Ct) (COLMAN J) that the order permitting service on the NR defendants and PICZ would be set aside. (1) PICZ was entitled to be heard as it was not in breach of any undertaking. The court had a discretion to hear the NR defendants given that they were in contempt, but would exercise its discretion to do so. Where a person in contempt sought to challenge the jurisdiction of the court which made the order which he had broken it was generally right that he should be heard (see paras 11 and 14); -X Ltd v Morgan Grampian (Publishers) Ltd [1991] 1 AC 1; Motorola Credit Corporation v Uzan (No 2) [2004] 1 WLR 113, applied. (2) The expression "Local Law and Jurisdiction Clause" in the cover note referable to the Zambian contract was sufficiently certain to mean that the policy was to be governed by Zambian law and that all disputes arising under it were to be determined by the Zambian courts. A contractual non-exclusive Zambian jurisdiction clause would have added nothing to the position, and in the improbable event that it had been intended by either party to insert a non-exclusive jurisdiction clause the cover note would have said so in express terms (see paras 22, 23 and 24). (3) The exclusive jurisdiction clause should be given effect. (a) It was not open to a party seeking to justify service outside the jurisdiction in contravention of a foreign jurisdiction to rely as grounds for strong cause or reasons the risk of inconsistent decisions of different courts when he ought to have appreciated the existence of that risk at the time when he entered into the exclusive jurisdiction clause (see para 32); -British Aerospace plc v Dee Howard Co [1993] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 368, Mercury Communications Ltd v Communication Telesystems International [1999] 2 All ER (Comm) 33, applied. (b) Although it was clear from the authorities that the risk of conflicting decisions was a consideration of considerable weight in the discretionary analysis, each case had to be tested by reference to its own [2006] Vol. 2 QBD (Comm Ct) LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS Konkola Copper Mines plc v Coromin Ltd facts. In the present case, the just, cost-effective and consistent determination of all the issues could only be achieved if they were all determined by the same tribunal. However, for the court to permit KCM to pursue the proceedings against the Zambian insurers in the interests of avoiding fragmentation of the proceedings would in substance be permitting KCM to avoid the foreseeable consequences of the contractual structure which they themselves created. In those circumstances justice did not require that KCM should be permitted to break their contract in order to cure the consequences of the very fragmentation which they had created. To enable joinder of the Zambian defendants in such a case would be a serious misuse of the necessary or proper party jurisdiction (see paras 41 and 42); -The Eleftheria [1969] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 237, Citi-March Ltd v Neptune Orient Lines Ltd [1997] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 72, Mahavir Minerals Ltd v Cho Yang Shipping Co Ltd (The M C Pearl) [1997] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 566, Donohue v Armco Inc [2002] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 425, Bas Capital Funding Corporation v Medfinco Ltd [2004] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 652, Antec International v Biosafety [2006] EWHC 47 (Comm), applied. ____________________ The following cases were referred to in the judgment: Antec International v Biosafety [2006] EWHC 47 (Comm); Aratra Potato Co Ltd v Egyptian Navigation Co (The El Amria) (CA) [1981] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 119; Bas Capital Funding Corporation v Medfinco Ltd [2004] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 652; British Aerospace plc v Dee Howard Co [1993] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 368; Citi-March Ltd v Neptune Orient Lines Ltd [1997] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 72; Donohue v Armco Inc (HL) [2002] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 425; Eleftheria, The [1969] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 237; Mahavir Minerals Ltd v Cho Yang Shipping Co Ltd (The M C Pearl) [1997] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 566; Mercury Communications Ltd v Communication Telesystems International [1999] 2 All ER (Comm) 33; Motorola Credit Corporation v Uzan (No 2) (CA) [2004] 1 WLR 113; X Ltd v Morgan Grampian (Publishers) Ltd (HL) [1991] 1 AC 1. ____________________ This was an application by the second to sixth defendants to set aside service on them of English proceedings outside the jurisdiction. TAG Beazley QC and Philip Edey, instructed by Pinsent Masons and Freshfields, for the claimants; 447 Colman J David Edwards, instructed by Norton Rose for the second, fourth, fifth and sixth defendants; Tim Penny, instructed by Cartier & Co, for the third defendant. The further facts are stated in the judgment of Colman J. Tuesday, 16 May 2006 ____________________ JUDGMENT Mr Justice COLMAN: Introduction 1. There are before the court two applications. Both of them are directed to setting aside orders giving permission to serve these proceedings on the second to sixth defendants in Zambia which is where all those defendant companies are incorporated and carry on business as insurers. The facts giving rise to the claim against them by the claimants are set out in paras 5 to 11 of my judgment dated 10 May 2005 ([2006] Lloyd's Rep IR 71). I refer to the second, fourth fifth and sixth defendants as "the NR defendants" and to the third defendant as "PICZ". All those defendants are collectively referred to in my earlier judgment as "the local insurers". The main issue in that previous application was whether the Part 20 proceedings by Coromin against the reinsurers should be stayed pending the determination of issues which arose between KCM, Coromin and the local insurers. KCM asserts that it was insured for 100 per cent of the risk by Coromin under the CCIP/Coromin policy on an all risks basis under which it is entitled to recover in respect of the Nchanga mine disaster or alternatively that it is entitled to recover under the DIC clause, set out in para 12 of the earlier judgment. It also asserts that it was insured in parallel by the local insurers on terms which differed in important respects from the CCIP/Coromin policy. In particular, as appears from para 11 of the earlier judgment, it was insured on a specified perils basis, one of the perils being "collapse including shaft collapse". Thus, whereas the Zambian contract would not respond to losses not caused by any of the specified perils, including collapse, the CCIP/Coromin policy had a wider scope and responded on all risks basis. The Zambian contract also contained a Zambian Law and Jurisdiction clause but the CCIP/Coromin contract contained an English Law and Jurisdiction clause. 2. The local insurers were originally included as co-defendants in these proceedings and, as appears from para 20 of the earlier judgment, on 29 June [2006] Vol. 2 QBD (Comm Ct) LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS Konkola Copper Mines plc v Coromin Ltd 2004 KCM obtained leave to serve them outside the jurisdiction on the basis that they were 100 per cent direct insurers of KCM and necessary or proper parties to these proceedings against Coromin. On 27 and 29 October 2004 the local insurers applied to set aside service, accepting that they were 100 per cent primary insurers of KCM under the Zambian contract. 3. As appears from para 21 of the earlier judgment, on 9 March 2005 the local insurers and KCM/ARH settled that application to set aside service. The terms are summarised in para 21. They included that KCM/ARH would commence proceedings against the local insurers in the Zambian courts, that the local insurers accepted that they were 100 per cent primary insurers of KCM/ARH on terms including the provision as to specified perils, that in the English proceedings there should be a consent order staying the claims against the local insurers and that stay was to remain in place until final determination of the Zambian proceedings. Each side agreed to pay its own costs of the application and all further costs orders were to be treated as discharged. The consent order staying the NR defendants' application was made on 11 March 2005 and that staying PICZ's application on 18 March 2005. 4. These consent orders are not in exactly the same form. Thus NR defendants' order incorporated an undertaking that in the Zambian proceedings they would admit and not dispute or deny or otherwise put in issue that they for their respective proportions had provided 100 per cent cover. PICZ's consent order was not in the form of an undertaking to this effect but merely recited that PICZ agreed to that effect, namely that its proportion was 20 per cent which it would admit in any subsequent proceedings. Importantly, both consent orders provided that in the event that the local insurers were in breach of such undertakings or agreements, KCM/ARH could apply to the court to lift the stay in these proceedings. 5. In due course KCM/ARH commenced proceedings in Zambia against the local insurers claiming in respect of the same losses as in the English proceedings on the basis that the local insurers were 100 per cent primary insurers of KCM, 80 per cent underwritten by the NR defendants and 20 per cent by PICZ. 6. Notwithstanding the terms of the undertakings given to this court, the NR defendants served a defence in the Zambian proceedings by which they put in issue those proportions of the risk. It seems that they proceeded on the basis that they wished to keep alive their original assertion that the local insurers were collectively on risk only in respect of 10 per cent whereas Coromin was on risk for 90 per 448 Colman J cent. In this court Mr David Edwards on behalf of the NR defendants has frankly accepted that they were thereby in breach of their undertaking and, for that reason, in contempt of this court. 7. As for PICZ, there can, in my judgment, be no doubt that in as much as paras 5 and 14 of the defence in the Zambian proceedings made no admissions as to KCM's case as to the percentage of the risk accepted by PICZ, its service amounted to a breach of the terms of the settlement effected by the consent order. It is said in the second witness statement of Mr Silutongwe, served on behalf of PICZ, that as far as he is aware any breach of the consent orders was unintentional, albeit that no explanation is put forward as to how the error occurred. Moreover, although PICZ now seek to cure their breach of the consent order and settlement by amending their defence, no steps were taken to do so until after KCM/ARH had applied for the stay of these proceedings to be lifted. This was a long time after both the service of the NR defendants' defence in the Zambian proceedings and of KCM's reply in those proceedings in which it was pleaded that PICZ was estopped from resiling from its confirmation in the consent order that it carried 20 per cent of the risk. Had PICZ pleaded its defence in error or by reason of some misunderstanding, one would have expected an immediate response withdrawing that part of the pleading. None was forthcoming and it is therefore, in my judgment, impossible to infer that the pleading was the result of any mistake or misunderstanding. 8. In these circumstances, I have no doubt that both as regards the NR defendants and PICZ, the entitlement of KCM/ARH for the stay to be lifted under the terms of the consent order was engaged. Indeed, the NR defendants had by my order of 27 February 2006 consented to the lifting of the stay. 9. If the stays were to be lifted, however, the procedural consequence would not be that the NR defendants and PICZ inextricably became parties to these proceedings. The effect of the lifting of the step would go no further than placing the parties in the same position as they were in before the consent orders were made. That is to say, there would in particular remain to be determined the outstanding applications to set aside service on the local insurers outside the jurisdiction. 10. As regards the NR defendants, a question arises as to whether, given that they are in contempt which, unlike PICZ, they do not offer to purge by amending their Zambian defence, those defendants should be heard by this court on any matter other than mitigation of their contempt. 11. This is a matter for the discretion of the court as held by the Court of Appeal in Motorola Credit Corporation v Uzan (No 2) [2004] 1 WLR 113. In [2006] Vol. 2 QBD (Comm Ct) LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS Konkola Copper Mines plc v Coromin Ltd this connection, there is a well-developed approach to the exercise of that discretion which, although not an inflexible practice, is normally adhered to. In particular, the court will normally hear a contemnor where the purpose of the application is to appeal against the order disobedience to which has put him in contempt: see Motorola Credit Corporation v Uzan, supra, at page 128. Moreover, where the contemnor seeks to challenge the jurisdiction of the court which made the order which he has broken it is generally right that the contemnor should be heard: X Ltd v Morgan Grampian (Publishers) Ltd [1991] 1 AC 1 per Lord Oliver at pages 50-51. 12. In the present case the order broken was the vehicle for giving effect to the settlement of an issue as to this court's jurisdiction to hear the substantive claim against the NR defendants. That issue was left at large on condition of performance of the terms of the undertaking, failing which the stay might be lifted so reinstating the NR defendants' application challenging the exercise of jurisdiction. If that challenge were successfully made, this court would be shown to have had no exercisable jurisdiction over those defendants except for the limited purpose of determination of the issue of substantive jurisdiction. For this court to shut out these defendants from arguing that they should never have been brought before this court in the first place presents itself to me as a disproportionate response to non-performance of the terms of their undertaking. If it is indeed the position that this court should exercise no substantive jurisdiction the ex parte order should never have been made and the defendants should never have had to enter into the settlement agreement or to give the undertaking. 13. For these reasons I have heard submissions from Mr Edwards on behalf of the NR defendants. 14. PICZ is not in contempt for it was in breach of no undertaking and does not need any discretion any exercise to permit it to make submissions as to jurisdiction. The submissions 15. The NR defendants rely on one ground for setting aside service: that there was an exclusive Zambian Law and Jurisdiction clause in the Zambian contract. They point to the cover note which provides for "Local Law and Jurisdiction Clause". This, they contend, goes beyond an agreement to agree on the terms of such a clause and means "Zambian Law and Jurisdiction Clause". Moreover, it is to be construed as an exclusive Zambian jurisdiction clause. Reliance is placed on my analysis of the law and jurisdiction clause in the reinsurance contract between Coromin and the reinsurers 449 Colman J in my earlier judgment at paras 69-73. Mr Edwards then relies on the judgment of Brandon J. in The Eleftheria [1969] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 237 and the decision of the House of Lords in Donohue v Armco [2002] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 425, as well as the more recent decision of Gloster J in Antec International v Biosafety [2006] EWHC 47 (Comm) where there is set out a useful summary of the applicable approach where a party has commenced proceedings in a jurisdiction other than that in the jurisdiction clause. 16. Mr Edwards submits that in the present case strong cause or strong reasons for permitting KCM/ARH to depart from the terms of the Zambian Law and Jurisdiction clause do not exist. In particular, all or most of the parties to the Zambian policy are in Zambia. The policy was broked in Zambia. It is subject to Zambian law. Many of the main issues have their "centre of gravity" in Zambia, in particular whether the events giving rise to the loss fell within any of the specified perils, specifically a "collapse", and whether the events of the broking exercise were such as to involve the local insurers in 100 per cent direct cover or only 10 per cent with Coromin as direct co-insurer for 90 per cent. Most of the many witnesses of fact were in Zambia. 17. It is further submitted that KCM/ARH, having entered into parallel contracts of insurance in respect of the same risk on different terms and, in particular, different terms as to law and jurisdiction must or ought to have foreseen that a situation might well arise where a dispute arose under one policy which had to be determined under English law in the English courts and where a dispute covering the same or overlapping ground arose under the other policy but had to be determined under Zambian law in the Zambian courts. Inconsistent decisions might thus result, an eventuality which therefore must have been foreseeable from the outset. That being so, the risk of inconsistent decisions having been brought about by KCM's own contractual structure, it should not be open to it to maintain that in the interests of justice it should be permitted not to comply with the Zambian Law and Jurisdiction clause in the Zambian contract. Although the issue as to whether Coromin was a direct insurer under the Zambian contract or was but a reinsurer of the local insurers was not foreseeable, that did not alter the position because the inconsistency in terms was engendered by or on behalf of KCM and would exist whatever the participation of Coromin. 18. Further, whatever course was taken in the English proceedings, it was probable that the Zambian proceedings would proceed in any event, an application to join Aon Zambia, the placing brokers, having already been issued by the NR defendants. It was unlikely that in these circumstances [2006] Vol. 2 QBD (Comm Ct) LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS Konkola Copper Mines plc v Coromin Ltd the Zambian judge would stay the Zambian proceedings. 19. Mr Penny, on behalf of PICZ, adopted the submissions on jurisdiction advanced by Mr Edwards. 20. On behalf of KCM/AH, Mr Tom Beazley QC relied heavily on the approach of the Court of Appeal exemplified in The El Amria [1981] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 119 and of the House of Lords in Donahue v Armco [2002] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 425 as well as on certain remarks made in the course of my earlier judgment in this case, at paras 84, 85, 102 to 112 and in the judgments in the Court of Appeal, notably the specific recognition by Rix LJ at para 27 that the risk of inconsistent decisions due to fragmentation of proceedings is where possible avoided even if that involves that an exclusive jurisdiction clause is not enforced. Mr Beazley submits that only if the Zambian Insurers are joined in these proceedings will all parties be bound by decisions on the issues arising between all of them. Given that it was KCM's case that there had been double primary insurance it was essential that the same court should decide liability under both the CCIP/Coromin policy and the Zambian contract and should decide how the double insurance clause in the CCIP/Coromin policy should be applied. Further, inconsistent decisions of different courts on the coverage issue as to whether KCM was insured as to 100 per cent or 10 per cent by the Zambian insurers could leave KCM with a gap in primary cover of 90 per cent. The operation of the DIC cover provided by Coromin potentially depends on the extent, if any, to which cover under the Zambian contract was less than under the CCIP/Coromin policy. It is submitted that even if this risk of inconsistent decisions was foreseeable, the interests of justice require that all parties should be subject to a trial by one court in spite of the Zambian jurisdiction clause. KCM draw attention in particular to para 28 of the earlier judgment where I observed: It will therefore be seen that the just, cost-effective and consistent determination of all the issues could only effectively be achieved if they were all determined by the same tribunal. 21. KCM further submits that arguments advanced in favour of setting aside service out are of comparatively little weight. There is little or no material different between Zambian law and English law and issues of Zambian law will have to be determined in the English proceedings in any event in relation to the claim against Coromin. Even if the claim against the Zambian insurers takes place in Zambia many of the witnesses of fact will still have to travel to England to give evidence here because of the need to determine the same factual issues. 450 Colman J Even if the experts have to visit the mine it is more convenient and cost-effective if they only have to give evidence at one trial. The number of Zambian witnesses who would have to give evidence in England on the structure of the insurance would be likely to be few. The costs of a Zambian trial might well be less than those of an English trial, but if there were two trials KCM would have to bear two lots of costs. Further, even if Aon Zambia were joined in the Zambian proceedings, the Aon Group too, would have to bear two lots of costs. Moreover, the Zambian insurers could join Aon Zambia in these proceedings if they remained parties. Discussion 22. I accept the submission of the Zambian insurers that the expression "Local Law and Jurisdiction Clause" in the cover note referable to the Zambian contract is sufficiently certain to mean that the policy is to be governed by Zambian law and that all disputes arising under it are to be determined by the Zambian courts. Neither party could in the circumstances of this risk have had the slightest doubt that "Local" referred to Zambia. An underwriter or a placing broker confronted with these words, I have no doubt, would have understood them as a mutual transitive reference of such disputes to the Zambian courts and not as a mutual promise not to object to the jurisdiction of the Zambian courts if that were invoked. Both the placing brokers (Aon, Zambia) and the five insurers would have had in mind the provisions of section 79 of the Zambian Insurance Act which provides: (1) The holder of a policy shall, notwithstanding any contrary provision in the policy, be entitled to enforce his rights under the policy against the insurer named in the policy in any competent court in Zambia. (2) Any question of law arising in any action under a policy which is instituted by the policy holder against the insurer named in the policy shall, subject to the provisions of this Act, be determined in accordance with the law of Zambia. 23. A contractual non-exclusive Zambian jurisdiction clause would thus have added absolutely nothing to that which to the presumed knowledge of all concerned was incorporated as a matter of Zambian law. 24. In the improbable event that it had been intended by either party to insert a non-exclusive jurisdiction clause the cover note would have said so in express terms. 25. It follows that KCM's attempt to join the Zambian insurers as parties to these proceedings was in breach of that exclusive jurisdiction clause. [2006] Vol. 2 QBD (Comm Ct) LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS Konkola Copper Mines plc v Coromin Ltd 26. That being so, are the circumstances such that this court should not give effect to that clause because there is strong cause, to use the well-established phrase used by Brandon J in The Eleftheria, supra, and approved by the Court of Appeal in The El Amria, supra and by the House of Lords in Donahue v Armco [2002] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 425 where "strong reason" was used to substantially the same effect? 27. It is to be observed that in The El Amria, both Brandon LJ and Stephenson LJ considered that the case was close to the borderline. In that case a stay of English admiralty proceedings was refused notwithstanding an Egyptian exclusive jurisdiction clause on the grounds that strong reasons had been shown, in particular the location of the preponderance of evidence in England, which was where the damaged cargo was discharged, and the risk of inconsistent decisions arising from the commencement of proceedings in England against the English port authority advancing an alternative claim for cargo damage due to delay in discharge. 28. The undesirability in the interests of justice of the risk of inconsistent decisions in proceedings in the exclusive jurisdiction court and those in the English courts and the weight to be attached to that consideration upon an application to stay English proceedings was emphasised in my own decision in Citi-March Ltd v Neptune Orient Lines Ltd [1997] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 72 at 77 to 78 and by Rix J in Mahavir Minerals Ltd v Cho Yang Shipping Co Ltd [1997] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 566. The latter was another case where a stay of English admiralty proceedings was refused, there being an exclusive Korean jurisdiction clause in bills of lading. The main grounds for refusal was the desirability of concentrating in one jurisdiction (England) all the many claims (125 plaintiffs suing under 62 bills of lading) in order to avoid inconsistent decisions and to minimise costs. 29. Similarly, in Donohue v Armco [2002] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 425, a claim for an anti-suit injunction to restrain New York proceedings on the grounds of an English exclusive jurisdiction clause, it was held that in the interests of justice an anti-suit injunction should be refused on terms as to abandonment of RICO claims in the New York proceedings. The basis of this decision was the desirability of the same tribunal determining all issues between all parties, including those not bound by the English jurisdiction clause, particularly having regard to the fact that a conspiracy was alleged by the defendant against the claimant and others, many of those concerned having no connection with England and not being independently amenable to the jurisdiction of the English courts. It was held that the relevant overseas-based defendants should not be served outside the jurisdiction. The substance of the 451 Colman J matter was that those defendants who had commenced the proceedings in New York against parties not bound by the English jurisdiction clause had done so perfectly properly and to separate off the claimant's proceedings by means of an anti-suit injunction would give rise to parallel proceedings and the risk of conflicting decisions. 30. At this point it is necessary to go back in time to an earlier decision of this court - that of Waller J in British Aerospace plc v Dee Howard Co [1993] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 368. In that case an application was made to set aside service on the defendants and that the action be stayed on the grounds that proceedings had been commenced by them against the claimant in Texas and that the Texas court was the more appropriate forum. Those applications were dismissed. Waller J first determined that there was an exclusive English jurisdiction clause in the relevant contract. He then considered the position if there were a non-exclusive English jurisdiction clause with particular regard to forum non conveniens considerations and in so doing introduced a consideration which is particularly relevant to the present application. This appears in a passage from his judgment at pages 376-377: It seems to me on the language of the clause that I am considering here, it simply should not be open to DHC (the defendant) to start arguing about the relative merits of fighting an action in Texas as compared with fighting an action in London, where the factors relied on would have been eminently foreseeable at the time that they entered into the contract. Furthermore, to rely before the English court on the factor that they have commenced proceedings in Texas and therefore that there will be two sets of proceedings unless the English court stops the English action, should as I see it simply be impermissible, at least where jurisdiction in those proceedings has been immediately challenged. If the clause means what I suggest it means that they are not entitled to resist the English jurisdiction if an action is commenced in England, it is DHC who have brought upon themselves the risk of two sets of proceedings if, as is likely to happen, BAe commence proceedings in England. Surely they must point to some factor which they could not have foreseen on which they can rely for displacing the bargain which they made ie that they would not object to the jurisdiction of the English court. Adopting that approach it seems to me that the inconvenience for witnesses, the location of documents, the timing of a trial, and all such like matters, are aspects which they are simply precluded from raising. Furthermore, commencing an action in Texas, albeit that may not be a breach of the clause, cannot give them a factor on which they can rely, unless of course [2006] Vol. 2 QBD (Comm Ct) LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS Konkola Copper Mines plc v Coromin Ltd that action has continued without protest from BAe. One can well imagine that if BAe had taken part in the proceedings in Texas without protest and if the proceedings had reached the stage at which enormous expenditure had been incurred by both sides and the matter was accordingly nearly ready for trial in Texas, that such factors would obviously lead the English Court to exercise its discretion in favour of setting aside service of proceedings. That is very far from being the situation in relation to the Texas proceedings so far commenced. In relation to the only other factor which it seems to me could be said to be one not foreseeable when the contract was entered into, the Cambridgeshire factor, I am not persuaded that the expertise undoubtedly achieved by the lawyers for DHC in other actions should be a factor which overrides the contractual bargain of DHC that they would not object to the jurisdiction of the English Court. It is thus clear to me that the proper approach to a case of the sort that I am considering is to consider it as equivalent to proceedings commenced as of right, to apply the passage in Lord Goff's judgment in The Spiliada dealing with such actions, but to add the consideration which he did not have in mind as pointed out by Mr Justice Hobhouse in Berisford, that there is a clause under which DHC had agreed not to object to the jurisdiction. That being the proper approach, and additionally, it being (as in my judgment it is) right only to consider the matters which would not have been foreseeable when that bargain was struck, I would dismiss both summonses of the defendants. 31. The concept that it is not normally open to an overseas defendant seeking to set aside service in the face of a non-exclusive English jurisdiction clause which had been freely negotiated to rely in support of a forum non conveniens argument on factors of inconvenience which he ought reasonably to have appreciated might arise when he entered into the jurisdiction agreement presents itself to me as entirely correct in principle. Were it otherwise, it would be open to a defendant to invite the court to exercise a discretion to enable him to escape from his contract for reasons of which he ran the risk of occurrence from the outset. In such circumstances procedural inconvenience clearly has to yield to the public policy of holding him to his contract. 32. I have no doubt that if, as I am sure, that approach should be applicable in the case of the forum non conveniens analysis required in the case of a non-exclusive jurisdiction clause, it must in principle also be applicable to the "strong cause/strong reasons" analysis required in the case of an exclusive jurisdiction clause. Thus, for example, it should not be open to a party seeking to justify 452 Colman J service outside the jurisdiction in contravention of a foreign jurisdiction to rely as grounds for strong cause or reasons the risk of inconsistent decisions of different courts when he ought to have appreciated the existence of that risk at the time when he entered into the exclusive jurisdiction clause. 33. In Mercury Communications Ltd v Communication Telesystems International [1999] 2 All ER (Comm) 33 Moore-Bick J said of judgment of Waller LJ at page 41: In principle I would respectfully agree with that approach. Although I think that the court is entitled to have regard to all the circumstances of the case, particular weight should in my view attach to the fact that the defendant has freely agreed as part of his bargain to submit to the jurisdiction. In principle he should be held to that bargain unless there are overwhelming reasons to the contrary. I would not go so far as to say that the court will never grant a stay unless circumstances have arisen which could not have been foreseen at the time the contract was made, but the cases in which it will do so are likely to be rare. 34. In Bas Capital Funding Corporation v Medfinco Ltd [2004] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 652 at page 678 Lawrence Collins J, having considered the earlier authorities, observed: 192. I am satisfied that it would require very strong grounds to override a choice of English jurisdiction, and that the normal forum conveniens factors have little or no role to play, especially where it could be inferred from the lack of other connections with England that the parties had chosen the English forum as a neutral forum. In some cases the fact that the clause was non-exclusive might make it easier to displace the strong presumption in favour of upholding the choice, particularly where more than one jurisdiction was chosen, but that would depend on the circumstances. 193. It would not be useful to speculate on what exceptional circumstances would justify the court in not accepting jurisdiction where the parties had conferred non-exclusive jurisdiction on the English court, but I accept that one feature which may be highly relevant is whether there are already proceedings in a foreign country which involve overlapping issues, especially if they have been commenced by the party which subsequently seeks to sue in England. 35. In the present case it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the only basis upon which application to serve these defendants out of the jurisdiction was made and the application granted was that they were necessary or proper parties under CPR 6.20(3). Accordingly, none of them [2006] Vol. 2 QBD (Comm Ct) LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS Konkola Copper Mines plc v Coromin Ltd could have been the subject of an order for service out on the basis of any other connecting factor under CPR 6.20. Their status as potential parties to these proceedings is therefore founded only on the kind of case management considerations which would justify joinder of defendants within the jurisdiction: see CPR 19.2(2). In other words KCM/ARH's claim has no connection whatever with this jurisdiction. All the parties to the claim on the Zambian contract are incorporated in Zambia, except ARH, which incorporated in Luxembourg but is the indirect subsidiary of an English company. The Zambian contract was made in Zambia and is governed by Zambian law. The events giving rise to the loss occurred in Zambia. All the primary facts are located in Zambia. The alleged breach of contract by non-payment of the claim occurred in Zambia. But for the fact that KCM had commenced these proceedings against Coromin claiming in respect of the same casualty and had advanced an alternative claim against Coromin under the DIC clause in the CCIP/Coromin policy, KCM could not have commenced proceedings against the Zambian insurers in the English courts. The position is therefore that KCM now seeks to implead those defendants who have no connection with this country in order to consolidate the determination of issues in one jurisdiction in circumstances where KCM finds itself exposed to the risk of considerable financial loss if there are parallel proceedings in diverse jurisdictions. That loss is exemplified by the risk of conflicting decisions relevant to the operation of the DIC clause. If, for example, it is decided in this court that KCM has 100 per cent cover from the Zambian contract, whereas the Zambian courts decide that the Zambian contract provides only 10 per cent cover, the DIC clause is not engaged in respect of the 90 per cent gap. Further, for the purposes of the operation of the other insurance clause (see earlier judgment para 15) conflicting decisions as to what loss was recoverable under the Zambian contract could leave KCM without a significant recovery. 36. In early June 2000 KCM and Coromin agreed to an extension of cover for 24 months under the pre-existing Coromin policy. That policy period was unexpired on 8 April 2001 when the casualty occurred. 37. Between 30 June and 6 July 2000 the Zambian insurers agreed to extend cover under a pre-existing policy from 1 July 2000 to 30 June 2001. The period of that policy was also therefore unexpired at the time of the casualty. As I have said, KCM maintains that this policy provided cover in respect of 100 per cent of the risk. 38. At the time when that cover was placed with the Zambian insurers KCM therefore knew that it 453 Colman J would thereby be creating a double insurance structure. It also knew or ought to have known that, in order for it to be certain in the event of disputes that it achieved effective protection against losses under the DIC clause and/or by the operation of the other insurance clause in the Coromin policy, it needed entirely consistent decisions as to whether and if so to what extent it was covered under both the CCIP/Coromin policy and under the Zambian contract. Yet it entered into contracts of insurance with diverse law and jurisdiction clauses. 39. Against this background KCM/ARH invites this court to permit it to implead the Zambian defendants notwithstanding the exclusive Zambian Law and Jurisdiction clause and notwithstanding the fact that the claim against them has no connection whatever with this jurisdiction. For this purpose, it relies upon the procedural dislocation created by the diverse terms of the CCIP/Coromin and Zambian policies and the consequent risk of conflicting decisions as strong cause or strong reason for departure from the Zambian defendants' prima facie entitlement to enforcement of the Zambian jurisdiction clause by refusal of leave to serve out. 40. I am unable to accept this submission. 41. Although it is clear from the authorities to which I have referred that the risk of conflicting decisions is a consideration of considerable weight in the discretionary analysis, each case has to be tested by reference to its own facts. There are many cases, such as The El Amria, supra, where that which occasions the risk of conflicting decisions is the advent of a loss which engages the courts of a jurisdiction other than that provided for in an exclusive jurisdiction clause. Thus, in that case the shipowners' allegation that the cargo damage was the fault of the port authority led to the commencement by cargo owners in this country of proceedings against that party. Even though there was a palpable risk of conflicting decisions as to the cause of the damage if the shipowners had to be sued in Egypt, the Court of Appeal regarded it as a case "near the borderline": see Brandon LJ at page 128R and Stephenson LJ at page 129R. Similarly, in Citi-March v Neptune Orient, supra, although the bills of lading contained a Singapore exclusive jurisdiction clause, the situation arose where several parties handled the goods after discharge in Felixstowe and before delivery and none of those defendants were bound by the Singapore jurisdiction clause. In deciding that service against the shipowners should not be set aside this court held that there was strong cause for all those concerned with carriage and handling of the goods to be joined [2006] Vol. 2 QBD (Comm Ct) LLOYD'S LAW REPORTS Konkola Copper Mines plc v Coromin Ltd in one set of proceedings. There again the eventuality giving rise to conflicting decisions was adventitious and could not be regarded as foreseeable. 42. In the present case, as I observed in my earlier judgment, at para 28, the just, cost-effective and consistent determination of all the issues could only be achieved if they were all determined by the same tribunal. However, for this court to permit KCM to pursue these proceedings against the Zambian insurers in the interests of avoiding fragmentation of the proceedings would in substance be permitting KCM to avoid the foreseeable conse- 454 Colman J quences of the contractual structure which they themselves created. In my judgment, in these circumstances justice does not require that KCM should now be permitted to break their contract in order to cure the consequences of the very fragmentation which they have created. To enable joinder of these defendants in such a case would be a serious misuse of the necessary or proper party jurisdiction. 43. For these reasons the orders giving permission to join both the NR defendants and PICZ must be set aside.