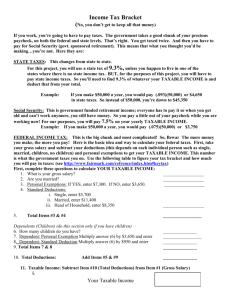

Do We (Now) Collect Any Revenue From Taxing Capital Income

advertisement