How to Read Literature Like a Professor

advertisement

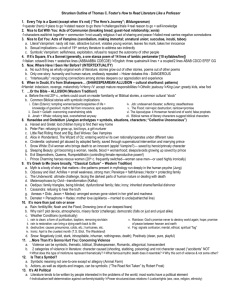

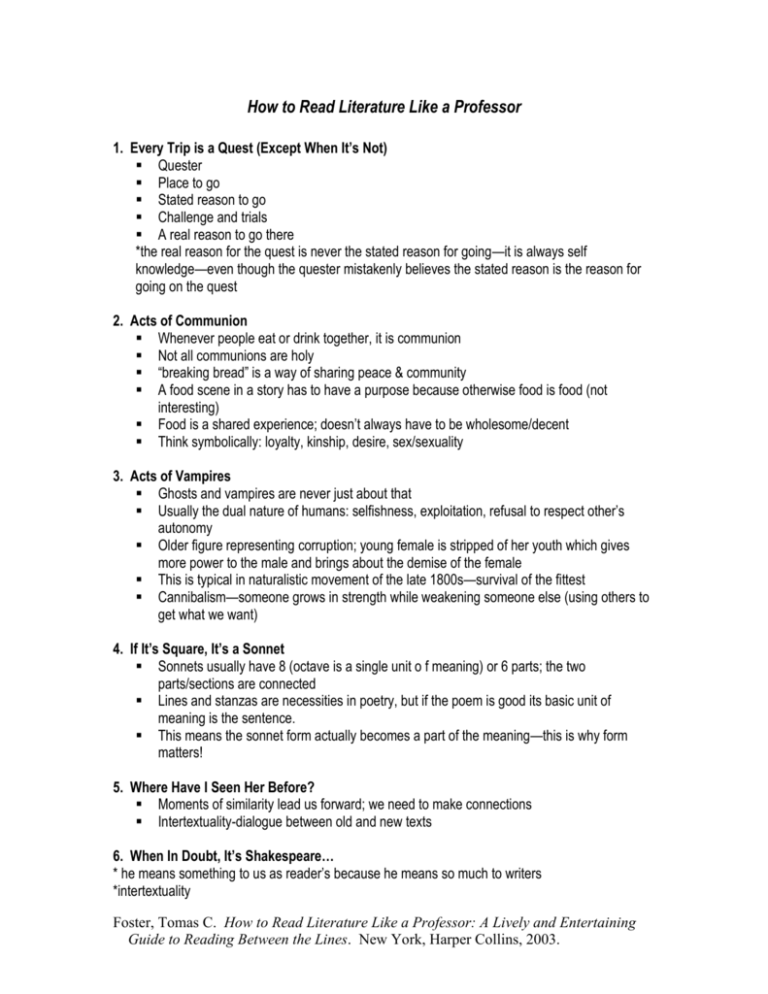

How to Read Literature Like a Professor 1. Every Trip is a Quest (Except When It’s Not) Quester Place to go Stated reason to go Challenge and trials A real reason to go there *the real reason for the quest is never the stated reason for going—it is always self knowledge—even though the quester mistakenly believes the stated reason is the reason for going on the quest 2. Acts of Communion Whenever people eat or drink together, it is communion Not all communions are holy “breaking bread” is a way of sharing peace & community A food scene in a story has to have a purpose because otherwise food is food (not interesting) Food is a shared experience; doesn’t always have to be wholesome/decent Think symbolically: loyalty, kinship, desire, sex/sexuality 3. Acts of Vampires Ghosts and vampires are never just about that Usually the dual nature of humans: selfishness, exploitation, refusal to respect other’s autonomy Older figure representing corruption; young female is stripped of her youth which gives more power to the male and brings about the demise of the female This is typical in naturalistic movement of the late 1800s—survival of the fittest Cannibalism—someone grows in strength while weakening someone else (using others to get what we want) 4. If It’s Square, It’s a Sonnet Sonnets usually have 8 (octave is a single unit o f meaning) or 6 parts; the two parts/sections are connected Lines and stanzas are necessities in poetry, but if the poem is good its basic unit of meaning is the sentence. This means the sonnet form actually becomes a part of the meaning—this is why form matters! 5. Where Have I Seen Her Before? Moments of similarity lead us forward; we need to make connections Intertextuality-dialogue between old and new texts 6. When In Doubt, It’s Shakespeare… * he means something to us as reader’s because he means so much to writers *intertextuality Foster, Tomas C. How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines. New York, Harper Collins, 2003. 7. …Or the Bible Situations and quotations from the Bible are more common than Biblical titles Poetry is full of scripture Writers prior to the middle of the 20th century were instructed in religion Most of the great human tribulations are detailed in scripture Allusions can be used to heighten religious thoughts or illustrate disparity or disruption (irony) Usually if it feels different in tone and weight from the rest of the prose, it is most likely biblical; it will be timeless and archetypal 4 horsemen come=apocalypse; pale rider=death Loss of innocence= the fall—Garden of Eden 8. Hansel & Gretel Shakespeare, The Bible, and folktales are all myths (timeless and archetypal, not in the religious sense—see section 9 myth definition) Usually stories of lost children who encounter strangers and want familiarity There is a sense of loss or transformation, temptation, fending for one’s self/oneself Can be an example of Metonymy-a part is made to stand for the whole (ex: Washington’s position represents all of America) 9. It’s Greek To Me Myth-shaping and sustaining power of a story and symbol; the ability of a story to explain ourselves to ourselves in ways that the sciences cannot Myth is a body of story that matters; stories that matter to a person in his/her community Can be overt subject matter or allusions Myths usually demonstrate our potential for greatness no matter how humble one’s worldly circumstances Common themes in myths: need to protect one’s family (nature); maintain dignity (divine); determination to remain faithful & to have faith (others); to return home (ourselves) 10. It’s More Than Just Rain and Snow Every story needs a setting and the weather is a part of it It’s never just rain—it can be action, paradoxical, mythological, symbolic etc… Paradoxes: it is clean but it makes mud; it transforms; it cleanses; it is restorative; new awakenings Water can mix with other things: corruption, rainbows (biblical allusion), fog, snow Snow: clean, stark, severe, warm (paradox), inhospitable, inviting, playful, filthy You need to always check the weather! 11. …More Than It’s Gonna Hurt You: Concerning Violence Violence=personal and intimate acts between humans It can be cultural, societal, symbolic, thematic, biblical, Shakespearean, Romantic, allegorical… Violence is typically symbolic action a. specific injury on one another or self b. narrative violence that causes characters harm in general (for the sake of plot advancement and characters aren’t responsible for it—author created it) Foster, Tomas C. How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines. New York, Harper Collins, 2003. 12. Is that a Symbol? *a symbol cannot be reduced to stand for only one thing. It MUST have a range of possible meaning & interpretation *if it can stand for only one thing on a one-to-one basis=allegory Five ways to analyze/interpret symbols a. determine if they are references or prior knowledge b. break the work into manageable pieces c. associate freely & take notes d. group thoughts into headings; accept and reject groupings e. Ask questions: What is the writer doing with this object, image, act, or movement of narrative? What does it feel like? 13. It’s All Political Few novels are meant solely for the sake of politics Opposition to European lit traditions 14. Yes, She’s a Christ Figure, Too Culture is influenced by its dominant religious systems Religion inevitably informs the literary work Christ figures are where you find them, and as you find them They can be female as well 15. Flights of Fancy Humans are earth bound, so if they are flying it is symbolic Symbols: freedom, escape, return home, spiritual, love Irony: falling, demise 16. It’s All About Sex Historically writers and artists couldn’t make much use of the real thing (censorship) When sex is encoded into the text, it can work on multiple levels (usually to protect innocence of the reader, audience members etc) Usually has to do with one’s identity Few works are explicitly about the act of sex itself. If it is, usually it is pornography 17. Except Sex When writing about sex it usually is really something else—otherwise it is cliché Symbols: pleasure, sacrifice, submission, rebellion, resignation, supplication, domination, enlightenment 18. If She Comes Up, It’s Baptism Look at how the character gets into the water. Are they rescued? Do they rise up? Drowns? Grabs drift wood? Etc. Rivers: suggest the constant shifting nature of time Herachitus said, “One cannot step into the same river twice.” Baptism: rebirth (whether God notices or not), old identity dies, can be painful,*you must be ready to receive it; 3 times=father, son, holy ghost Foster, Tomas C. How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines. New York, Harper Collins, 2003. Drowning serves its own purpose Symbolizes: character revelation, thematic development of violence, failure, guilt, plot complication, denouement 19. Geography Matters Every story is a vacation for the authors; He/she must choose where to go every time Geography is location + its people (history, politics, economics) Geography is about humans inhabiting space and how that space inhabits them It can always be symbolic, plot, theme, develops the character North/Up: clear views, snow, isolation, ice, purity, life, death, thin air South/Down: swamps, crowds, fog, darkness, feuds, heat, unpleasantness, people, life, death When characters go South/south, it is so they can run amuk=direct raw encounters w/ subconscious 20. So Does Season Seasons are so symbolically engrained we need to look for variation and nuance Seasons have certain measures of energy Something comes before and after them Irony: summer can be warm and liberating or hot and stifling 21. Marked For Greatness Marks tell us something thematically, metaphorically, symbolically Usually a hero is marked differently than the rest (strength, deformity etc) Often are cautionary elements Can outwardly project the perils of man seeking to play good, or hideous outer form hides one’s inner beauty 22. He’s Blind For a Reason You Know Images of light and dark have everything to do with seeing or not Literary blindness: as soon as you see it as thematic, more related images/phrases will emerge Learn to recognize what questions to ask: Does it set up a pattern or reference? What does the author intend by this? Seeing and blindness are in so many works even when there is no direct hint—so if it is there all the time, what’s the point of introducing it specifically into some stories? SHADING & SUBTLEY If you want your audience to know something important about your character, introduce it early before you need it 23. It’s Never Just Heart Disease… The heart is the center of emotion in the body; the heart never overstays its welcome Heart issues/ailments=bad love, loneliness, cruelty, disloyalty, pederasty, cowardice, lack of determination Characters can have heart trouble from the start or difficulties of the heart Look for irony Foster, Tomas C. How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines. New York, Harper Collins, 2003. 24. …And Rarely Just Illness Not all diseases are created equal The disease should be picturesque (pale skin, sunken eyes…) Mysterious in origin Have symbolic or metaphorical possibilities; metaphorical possibilities overrides all others This is why TB/consumption works Every age has its disease: TB, VD, AIDS AIDS is the “new” disease because it is geographic, political, social, cultural… All disease is about: transmission, incubation, duration There is a universality of great suffering and despair and courage of a victim seeking to wrest control over his own life away from the condition that has controlled him 25. Don’t’ Read With Your Eyes Have to read works in its context; take the work as it was intended Read with perspective of the time and your own—it allows for more sympathy w/ the historical moment of the story Texts are often written against its own social, historical, cultural and personal background Literary criticism is an option Caution: too much acceptance of the author’s POV can lead to difficulties; we don’t have to accept everything 26. Is He Serious? And Other Ironies IRONY TRUMPS EVERYTHING EX: Typically we see characters who are our own equals or superiors, but in an ironic work we watch characters struggle futilely with forces we might be able to over come Irony make great use of deflection from expectation IRONY SIGNIFIES A MESSAGE Ask yourself: How does it signify? What is the signifier? Reading Between the lines requires questions: How did you feel and what made you feel that way? How does it signify? What’s the signifier? Memory Patterns Metaphors Symbols Themes Irony Foster, Tomas C. How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines. New York, Harper Collins, 2003.