101.Ch 11. Mankiw

advertisement

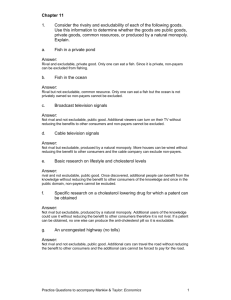

Ch 11. Public Goods and Common Resources -- Mankiw -- Principles of Microeconomics I. Introduction a. Motivation – examine the problems that arise for the allocation of resources when there are goods without market prices. -- Like the externalities chapter we will examine market failure and government action to remedy the problem. b. The Problem of Free Goods – prices are the signals that guide the actions of buyers and sellers. These forces are absent if the goods are free. II. The Different Kinds of Goods a. Two Key Characteristics – 1. Excludability – can people be prevented from using the good? 2. Rival in Consumption – Does one person’s use of the good reduce another person’s ability to use it? b. Figure 1 – creates 4 categories – 1. Private Goods are both excludable and rival in consumption. Example: ice cream cone. Possible to prevent someone from eating the cone and if A eats the cone B can’t. (Text assumed private goods in chapters 4 to 9.) 2. Public Goods – neither excludable or rival. Examples: uncongested local roads and parks, clean air, and national defense. Can’t prevent drivers from using local roads but if no congestion one person’s consumption won’t prevent others. 3. Common Resources – rival in consumption but not excludable. Examples: fish in the ocean, aquifers, large oil deposits. When one person catches a fish, there are fewer for others. But preventing individuals from fishing is impossible b/c of ocean’s size. 4. Natural Monopoly – Excludable but not rival. Examples: fire protection, cable TV. Easy to exclude someone from fire protection or cable TV but once the good is produced others can consume at low or no cost. c. Boundaries Between Categories – although Fig. 1 offers a clean separation of goods into the four classes, whether goods are excludable or rival is often a matter of degree. Consider common property classification of fish in the ocean. A large enough coast guard could make fish at least partly excludable. Although fish are generally rival, they might be non-rival if the number of fishermen was small relative to the population of fish. d. Relation Between Externalities and Common Property/ Public Goods – For both public goods and common resources externalities arise b/c something of value has no price attached to it. -- If one person were to provide a public good (e.g., a tornado siren) other people would be better off b/c they would receive a benefit w/o paying for it. -- Similarly, a when one person uses a common resource (i.e., fish in the ocean) people are worse off b/c there are fewer fish to catch – a negative externality. III. Public Goods a. The Free Rider Problem – Because public goods are not excludable, free market provision of these goods is difficult if not impossible. Free market provision is difficult b/c potential users of the good see that once the good is produced, no one can keep them from consuming it free of charge. -- Firms also realize this, so they don’t produce the good. This is a welfare loss b/c consumers are made better off by the good but have little incentive to reveal their actual valuations. Consider national defense. b. Externality of Public Goods – one way to view this market failure is that it arises b/c of an externality. -- Providing national defense or a fireworks display implies creation of a positive externality. But the individual producer does not take into account the externality. c. Solution: taxation and government provision. Mankiw develops his explanation in terms of fireworks displays but it applies to other public goods like national defense. -- If the government decides that the total benefits of a public good exceed its costs, it can provide the public good pay for it w/ tax revenue and make everyone better off. 1 IV. Some Important Public Goods a. National Defense – once the country is defended, it is impossible to prevent any single person from enjoying the benefits. -- In 2004, the federal government spent a total of $456 billion or $1,500 per person. b. Basic Research – distinguish between general knowledge and specific knowledge. Many types of specific knowledge may be patented (a new drug). Where a patent is possible, the inventor may exclude others from using that knowledge or charge a fee to use it. This allows the knowledge producer to capture the gains & there is no externality. -- By contrast, information about how the brain or the nervous system works is not patentable b/c it is not a useful invention. However, useful inventions may follow from this knowledge. This knowledge is non-rival in consumption & non-excludable. --Thus, there’s an incentive to free-ride & insufficient basic knowledge supplied by the free market. -- Remedy: Government funding of basic research through NSF, NIH. c. Fighting Poverty – advocates of antipoverty programs argue that fighting poverty is a public good b/c even if everyone prefers living in a society w/o poverty the market may not be able to provide it. Non-rival: one person’s enjoyment is not diminished if someone else enjoys it & good is not excludable. Thus, incentive to free ride on the antipoverty efforts of others. Government programs: TANF, EITC, Medicaid. d. Lighthouses – often think that lighthouses are a public good. My use of the light to find the harbor does not affect your ability to use it & once the light is produced you can’ keep others from consuming. -- Seems like a free rider problem. However, in 19 th century England lighthouses were often privately owned & the owner of the lighthouse charged the nearby port. If the port owner did not pay, the lighthouse turned off the light & ships avoided the port. --Thus, to decide whether something is a public good, we must determine who the beneficiaries are & whether they can be excluded. A free –rider problem emerges when the number of beneficiaries is large 7 they can’t be excluded. V. Costs-Benefit Analysis for Public Goods a. Why? – we know that public goods will be undersupplied and that government supply is often a superior alternative. -- Must determine, however, what goods & how much the government should supply. Should the highway be 2 lanes, 4 lanes or 6 lanes? How large should the park be? Should there be additional infrastructure investments? b. Analysis – to judge whether to build the highway it must compare the total benefits of all users to the cost of building and maintaining the highway. Difficulty – simply asking people how much they value the highway is not reliable b/c respondents have little incentive to tell the truth. Those who would use the highway have an incentive to exaggerate the benefits to get it built while those who would be harmed have an incentive to exaggerate the costs. c. Private v. Public Goods -- This does not occur w/ private goods where buyers have incentives to accurately reveal benefits through the prices they pay and sellers accurately reveal costs by prices they are willing to accept. The efficient equilibrium reflects this information. --These price signals are absent for public goods. VI. How Much is a Life Worth? a. Motivation – Life can’t be made perfectly safe and increases in safety are costly. We are therefore forced to tradeoff between safety and other goods. Example: about 40,000 people per year are killed in auto accidents in the US. Cut the number of deaths dramatically making cars that can go no faster than 20 mph. b. Connection to Public Goods – many of these safety investments have public good characteristics. How clean should we make the air and water? Are we willing to trade a reduction of $1,000 of GDP per person to cut particulates by 12% (and deaths)? c. Example – town can spend $10,000 to install a traffic light that (based on the best estimates) will reduce the risk of a fatal accident over the lifetime of the traffic light from 1.6 to 1.1%. -- To reach a decision, we must put a value on human life. Value can’t be infinite b/c it would cause paralysis – install a traffic light at every intersection, drive enormous cars, etc. Our private decisions are not consistent w/ this as we sometimes forgo safety features on cars, ski, bike without a helmet, etc. 2 d. Two Ways to Value Human Life – 1. Look at the total amount of money the person would have earned had they lived (often used in wrongful death suits). Economists are critical of this approach – it often reaches non-sensical results – retired or disabled people have no value. 2. Look at the risks that people voluntarily take and how much they must be paid to make them. Look at coal miners’ wages and the wages of those w/ similar training in safe jobs. If risk of death is about 1% higher and earn about $100,000 more over your lifetime, this implies $10 million value on your life. -- In fact, studies of this type show that typical value of a life is about $10 million. e. Back to the Traffic Light – If traffic light reduces risk of a fatality by 0.5 pct points, then $10 million x 0.005 = $50,000. Since the light only costs $10,000, install it. VII. Common Resources a. Relation to Public Goods – like public goods, common resources are not excludable. However, they are rival in consumption. b. Tragedy of the Commons – parable that shows outcomes when rival goods are not excludable. -- Consider a common grazing area. Anyone is permitted to use the area. Each livestock owner has no incentive to account for the costs they impose on others (the negative externality). – Add more livestock, it becomes more difficult for livestock already on the common to find food & the land becomes barren. c. Cause of the Problem – why does overuse occur? Social and private incentives differ. No single shepherd has an incentive to reduce the size of their herd b/c they are simply a small portion of the problem. -- If all shepherds acted together, they could solve the problem. Likewise, if there was a single owner of the resource, there would be no problem either. d. Solving the Problem – Can be solved a number of ways. Town can regulate the number of sheep on the common, internalize the externality by taxing the sheep, or auction off grazing permits. -- Another solution: divide up the land among the shepherds. Each shepherd can enclose their land and exclude others – turn the common property into a private good. VIII. Some Important Common Resources a. Clean Air and Water - clean air and water are common resources. Excessive pollution is like excessive grazing. b. Congested Roads – discussed below c. Fish, Whales and Other Wildlife – fish and whales have commercial value and anyone can go to the ocean and catch them. Because no one owns them, no one has the incentive to maintain sustainable stocks. -- The ocean remains one of the least regulated common resources. Why? 1. many countries have access to the ocean so solutions require international cooperation; and 2. Because the oceans are so vast, enforcement is difficult. -- Within the US various laws aim to protect fish and wildlife. 1. Charge for fishing & hunting licenses; 2. Limits on catch (or kills); 3. Restricted seasons; and 4. Size limits. d. Why is the Cow not Extinct? Bison nearly hunted to extinction. In Africa today, the elephant faces similar challenges. Why is the commercial value of ivory a threat to the elephant a threat but the cow a valuable source of food is not threatened? Cattle are privately owned but elephants roam freely. Governments have tried to save the elephant in two ways. 1. Some countries (Kenya, Uganda) make it illegal to kill elephants. However, these laws have been hard to enforce & elephant populations continue to fall. 2. Other countries (Botswana, Malawi, Namibia) have made elephants a private good by allowing them to kill elephants only if they are on their own property. Landowners now have the incentiveto preserve the species on their own land & as a result elephant populations have started to rise. IX. The Highway Problem a. Assumptions – 1. highway is uncongested off-peak but congested on-peak; 2. trip is ½ hour if highway is uncongested; 3. beyond a certain point, additional cars slow everyone down; and 4. there is a side street route that takes 1 hour. b. Chart – MC differs from AC. AC is the basis of decisions. MC > AC because an additional car slows average car by 3 min (after congestion) so MC rises b/c all cars already on the road slow by 3 additional minutes. c. Private Ownership & Common Property -- suppose that p = value of time on the side streets; AC(x) = value of time spent on the highway where x is the number of cars on the highway. 3 -- Thus, willingness to pay to use the highway is: t = p – AC(x). -- Total tolls (T) are indiv toll times the number of cars – T = tx. -- Thus, maximizing total tolls T = tx = px – AC(x)x = px – TC(x) → dT/dx = p – MC(x) = 0 → p = MC(x). -- This implies that the owner of the road will maximize profits if he sets the tool so that the MC of the freeway is equal to the value of time on the side streets. X. The Importance of Property Rights a. Property Rights, Externalities, and Common Property – In Chs. 10 and 11 we saw that there are some “goods” that are difficult to supply using free markets. Common theme: property rights. -- In all cases, the market fails to allocate resources efficiently b/c property rights are not well established. That is, some item of value does not have an owner w/ the legal right to control it. (Not exactly – transactions costs of trading the rights might be too high.) b. Examples –Clean air and national defense are goods but no one has the ability to attach a price to it and profit from its use. A factory pollutes too much b/c no one charge the factory for the pollution it emits. c. Solution – when the absence of property rights causes a market failure, government can potentially solve the problem – sell pollution permits, restrict the catch, or provide the good on its own (as in national defense). 4