Section Nine - Student Organizations

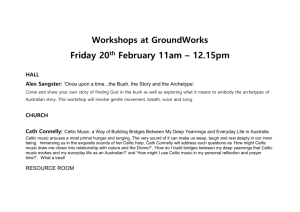

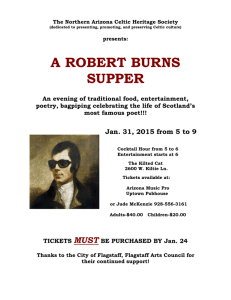

advertisement