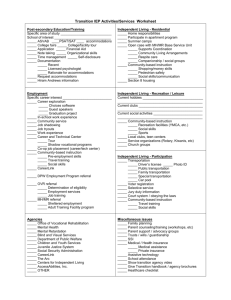

Enhancing career development

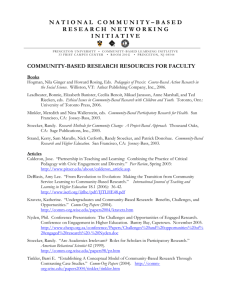

advertisement